This is part two of four in the Black swan in the Black sea series.

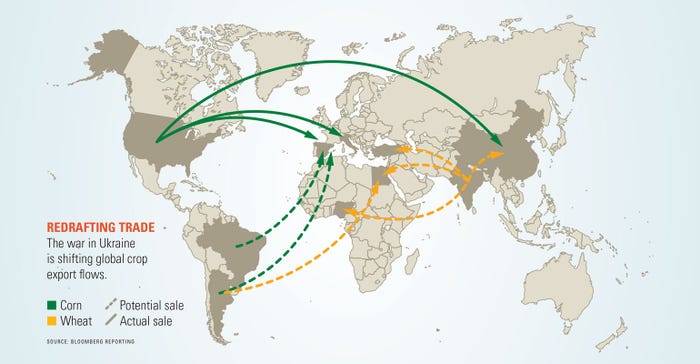

Russia and Ukraine traditionally combine for 29% of the world’s wheat exports. But upon the war’s outbreak, global wheat buyers immediately turned to countries with available supplies to book future shipments — Australia, India and South America.

After harvesting back-to-back bumper crops, Australia is poised to become the world’s third-largest wheat exporter this year. Australian export loading volumes are expected to triple to over 1 billion bushels this year from 2019-20 volumes. Export terminals are operating at maximum capacity and shipping slots are booked for months.

Abundant Australian rainfall this spring could point to another bumper crop as long as farmers don’t cut back on high-priced fertilizer applications leading to lower yields. Australia’s top grains exporter, CBH Group, has already had buyers book forward contracts for wheat shipments in the third quarter.

India is also stepping up. After sitting out of export markets due to anti-competitive government pricing policies and harvesting five consecutive bumper wheat crops, high market prices have outpaced wheat prices supported by the Indian government. This has incentivized the country to export its largest volume of wheat – ever.

India’s wheat export volumes are forecast just shy of 300 million bushels this year due in large part to the surging demand rates experienced in the three months since the Ukrainian war’s onset. India is expected to end the 2021-22 year as the world’s eighth-largest wheat exporter as its surpluses and location make it an affordable option for African, Middle Eastern and even Chinese wheat buyers.

Whether India can continue this trend is less certain. A heat wave this spring has caused drought stress that triggered the Indian government to suddenly ban wheat exports in mid-May in an effort to ensure domestic supplies. The government has relaxed the ban somewhat, but the actions were enough to inject more fear about potential supply shortages back into the markets.

Northern hemisphere wheat harvest looms large

Over the past five years, regions including the EU, U.S., Canada and Australia have accounted for 50% of the world’s wheat exports, on average with Argentine exports contributing another 7%. But the supply outlook going forward for these countries is a mixed bag.

U.S. winter wheat conditions battered by drought face an uphill battle to make trend-line yields. Planting delays for the spring wheat crop are also likely to result in subpar yields. The U.S. is a residual supplier of wheat, meaning its high freight costs leave it as a last resort option for hungry international buyers. Yield shortfalls this summer could deter future export potential.

Brazil — which typically imports wheat supplies from neighboring Argentina — is slated to nearly triple wheat exports this year. Export and weather incentives for 2022-23 Brazilian and Argentine wheat crops to be planted in the coming weeks could trigger an acreage expansion. But those acres will battle against high input prices and competitive substitute crop options, especially corn, for additional acreage.

As of mid-April only 62% of Ukraine’s winter wheat crop planted last fall was expected to be harvested this summer. That will leave Russian and EU wheat crops as the top choices for importers this summer.

EU wheat crops started the spring in idyllic condition. But a dry spell across top producer France generated additional concern for the region’s wheat exporting prospects in 2022/23. USDA is forecasting new crop wheat exports out of the EU will increase 16% next year to 1.32 billion bushels as global buyers become increasingly dependent upon EU wheat.

But that doesn’t mean that the EU will replace Russia’s position as the world’s top wheat exporter. Russian wheat crops are in great condition and several forecasters are hinting at record Russian wheat production this summer.

Dmitry Rylko, the head of the IKAR agriculture consultancy, expects the 2022 Russian wheat crop will reach 3.12 billion bushels. Rylko considers the forecast to be a “conservative” estimate. USDA currently projects the 2022/23 Russian wheat crop at 2.94 billion bushels.

If IKAR’s forecast is realized, it would trail the 2020 (3.14B bu.) and 2017 (3.13B bu.) Russian crops that currently stand as the largest and second largest crops on record. That means the 2022 crop would be the third largest.

This would likely give Russian exportable wheat supplies a comfortable boost in volume, despite lingering economic sanctions that create additional challenges for Russian wheat exporters. That means that tightening supply pressure on the global wheat complex could be reduced in the coming weeks, especially as more global wheat buyers find loopholes around the sanctions to procure Russian wheat supplies.

Noted Black Sea consultancy SovEcon countered IKAR’s projections this morning at press time, issuing a 2022/23 Russian wheat forecast of 3.26 billion bushels, which would be a record high for Russian wheat production in the post-Soviet era.

"The chance of exceptional winter crop in Russia is rising as we pass one milestone after another,” said Andrey Sizov, managing director of SovEcon. “The emergence of plants after the winter and March-April weather was an important stage and plants look better after it. Looking at the weather forecast for the next weeks we don’t rule out the possibility of a further increase in the forecast.”

High-yielding crops from both Russia and the European Union, which traditionally jockey for the title of world’s largest wheat exporter, will reduce supply worries through summer, even if Russian banking sanctions remain.

USDA’s take on Black Sea trade flows

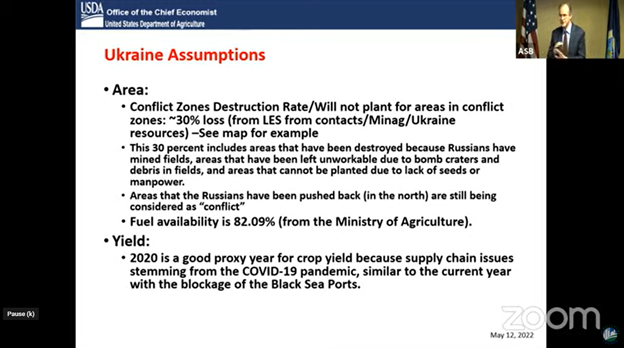

The World Agriculture Outlook Board, the USDA division that publishes WASDE figures, drew similar parallels between the 2020 pandemic year and the current year’s ongoing Russian invasion in Ukraine to determine 2022 Ukrainian production estimates in its latest forecast, released in mid-May 2022.

The board’s assumptions about Ukraine are laid out below and do not suggest dramatic yield shortfalls for Ukrainian crops this year, though only around 70% of available crop ground will likely be utilized this year. Fewer hybrid seeds were likely imported amid the Russian invasion, so high-yielding varieties planted in Ukraine are likely to be few and far between this year.

In 2020, Ukrainian farmers faced similar accessibility issues to fertilizer, fuel, and other inputs amid the pandemic, so WAOB modeled its 2022 Ukrainian estimates closely on 2020 production and trade results. The agency outlined additional assumptions it used to create its forecasts in the graphic below.

In a May Crop Production and WASDE briefing with the Secretary of Agriculture livestreamed on YouTube following the reports’ release, The chairman of the WAOB, Dr. Mark Jekanowski, shared satellite data that featured images of bomb craters and land mines in Ukrainian fields. But those images also showed that Ukrainian farmers continue planting activity regardless of the ongoing war.

Ukraine is going to have a muted impact on grain and oilseed markets this year, according to USDA’s first look at 2022/23. The country’s 2022/23 wheat production was forecast nearly 423 million bushels (-35%) lower on the year to 790 million bushels. Ukrainian agriculture minister Mykola Solskyi said last Friday that half of Ukrainian winter wheat acres are currently in areas besieged by Russia or in the midst of ongoing battles.

As a result, Ukrainian exports are likely to be significantly less than last year, keeping global grain and oilseed supplies uncomfortably tight. Wheat exports are expected to fall 47% from the previous year. These wartime estimates are subject to revision but could be negatively impacted on Russia’s ongoing military strategy.

Russia is slated to be the world’s largest wheat exporter next year thanks to forecasts for a bumper crop coming this summer. USDA was clear in defining how those shipments would circumvent banking restrictions currently imposed on Russia due to its unprovoked military occupation of Ukraine.

But based on market chatter over the past couple months, we know that certain international institutions are finding ways to issue letters of credit and insurance policies, trade outside of the dollar system, use non-sanctioned Russian banks, and other financial strategies to ensure adequate food and fertilizer supplies.

To be sure, these are neither cheap nor efficient methods. But the world is going to get its hands on Russia’s massive wheat crop – and potentially some of Ukraine’s crops if Russian forces continue their advance through Southeastern Ukraine – one way or the other.

For further supply and demand analysis about USDA’s 2022/23 estimates for Black Sea production and trade, check out my latest E-corn-omics article on the topic.

Russian wheat not completely off the market

Russian export terminals in the Black Sea have largely resumed loading wheat shipments. The International Grains Council expects it will end up shipping 2% less in grain volumes this year due to sanctions.

“While loadings [in Russia] recently resumed, volumes may be hampered by trade finance restrictions and additional ocean freight insurance requirements,” the IGC said in mid-March.

But the sanctions aren’t going to keep Russia out of the wheat export market for long. With a record harvest expected this summer, USDA projects that Russia’s wheat export volumes will grow to a staggering 1.4 billion bushels in 2022/23 – 18% higher than current year forecasts.

Who’s buying that grain? It’s not clear, especially since costly premiums must be paid to trade in rubles instead of dollars. But there are some clues. India has eagerly booked purchases of cheap Russian oil following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In early February, China approved Russia’s phytosanitary standards to allow for wheat and barley purchases from Russia.

As the world’s largest grain buyer, China could easily redirect its wheat purchases exclusively to Russia and away from the EU, U.S., Canada and Australia. Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council, has suggested that Russia would not blink at sharing food supplies with allies — only.

“We will only be supplying food and agriculture products to our friends. Fortunately, we have plenty of them, and they are not in Europe or North America at all,” Medvedev said via social media in early April.

This is part two of four in the Black swan in the Black Sea series. Tomorrow’s article (part 3) will examine the impact of the Black Sea conflict on global fertilizer markets. It will also feature updated analysis from the latest USDA-World Agricultural Supply and Demands Estimate report issued in early May on global acreage shifts that could impact next year’s fertilizer prices.

Read more:

Black swan in the Black Sea: corn

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like