In a scene rivaling the iconic movie “Field of Dreams,” four farmers walked into the edge of a cornfield and disappeared. They were attending a Syngenta Grow More Experience field day this summer in Columbia, Mo.

Minutes later, the men reappeared through the rows, calling out numbers.

After quick addition, Brett Craigmyle, agronomist for Syngenta, proclaimed, “Twenty-seven. That is the number of giant ragweed you found in just this 600-foot area.” Then he asked the group how much those 27 weeds would cost farmers. Silence.

Craigmyle says farmers need to start doing the math on weeds; some are costlier than others.

Field-robbers

A driver weed is one that influences yield or long-term weed management plans. In corn, Craigmyle looked at three — giant ragweed, cocklebur and waterhemp. Of those, he notes that giant ragweed is making a comeback in Midwest farm fields.

WEED ID: Here is a giant ragweed plant in between rows of corn. Syngenta agronomist Brett Craigmyle says at this stage, the leaves resemble “T-rex” (Tyrannosaurus rex) hands.

One of the earliest summer annuals to appear in the spring, its leaves resemble a “T-rex [Tyrannosaurus rex]” hand with three to five leaves. As it matures, those leaves broaden, taking up more energy, water and nutrients. “It competes heavily with corn plant,” he says.

When it comes to water, a giant ragweed plant uses almost two-and-a-half times more water than a corn plant to produce 1 pound of dry matter. It must grab the water from somewhere, so it steals from corn plants.

Giant ragweed also takes up a significant amount of nitrogen. If left untreated, Craigmyle says the weed can take up as much of 93 pounds of nitrogen per acre.

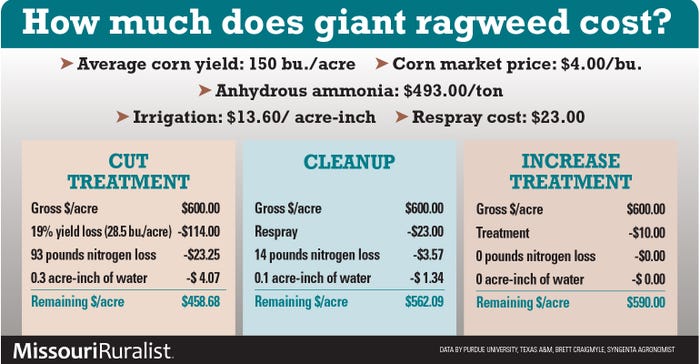

Season-long competition with those 27 giant ragweed results in a 19% yield loss for corn farmers. In the table below, Craigmyle breaks it down by the pocketbook.

Worth treatment

Over the years, as corn price declines, crop inputs have not followed suit. This leaves farmers searching for ways to save money. One place many consider is chemical control of weeds. Craigmyle cautions against it. “Weeds are aggressive,” he says. “Is it truly worth saving money but giving up weed control?”

Craigmyle says paying a slightly higher price for a robust, effective residual herbicide up front could save several dollars on the back end.

“You need to know driver weeds,” he says. “You need to know what it takes to control them, and then decide what these weeds will cost you at harvest.”

Waterhemp is another weed to watch. While it does not compete as heavily with corn as giant ragweed, it does have a large seed bank. Each plant can produce 250,000 seeds. “If untreated, this one poses a threat for weed control for years,” Craigmyle says.

Companies have a wide range of products at various price levels, he says, so finding something that works for the weed and the budget is possible.

This growing season, take some time and disappear into your own corn rows to look for weeds. Identify your driver weeds and plan for control next year. If not, Craigmyle says, it could cost you.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like