Travis Winans believes that any tool a farmer can use to prevent weed seed from returning to the soil surface is going to be valuable.

The University of Missouri graduate student, who is studying weed science under MU weed scientist Kevin Bradley, says the spread of herbicide-resistant weeds such as waterhemp required researchers to investigate alternate methods of weed control.

“One of those methods is impact mills and harvest weed seed destruction,” Winans says during a MU virtual field day. “The idea behind this concept is to destroy any weed seed that passes through the combine, making it no longer viable and preventing the seed from returning to the soil seed bank.”

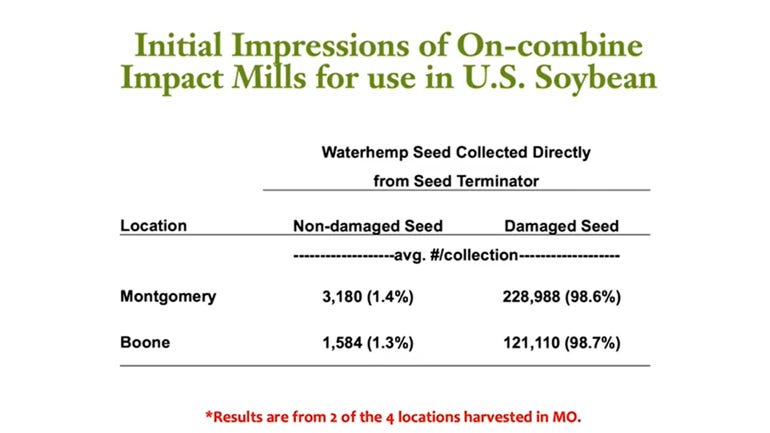

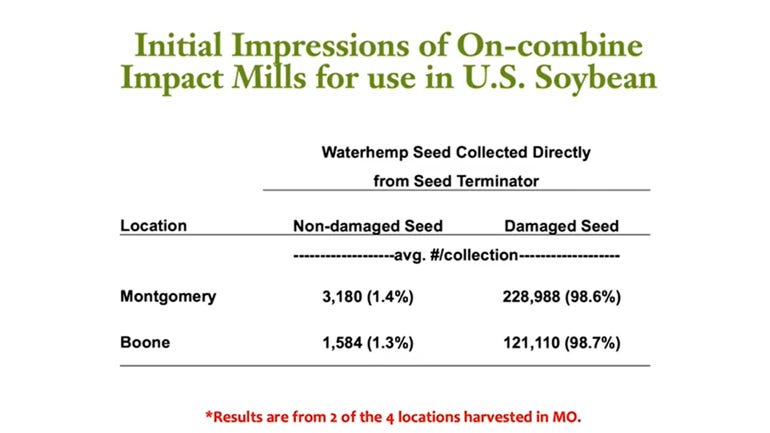

What he found was that more than 98% of weed seed was no longer viable after passing through the Seed Terminator.

How it works

The Seed Terminator is a multistage hammer mill.

The seed enters through the feed chute. It is then struck by “hammers,” or rectangular pieces of typically hard steel that are attached to a shaft that rotates — think your tractor’s power takeoff.

Then through a series of high revolutions, about 2,500 rpm, the seed is shattered by repeated hammer impact with the solid walls of the grinding chamber. “The stationary bars catch the chaff and the seed to further degrade the material,” Winans explains, “and what comes out of the mill is seed that is no longer viable.”

WEED CONTROL: After one year of research, MU researchers are finding promise in the Australia-based Seed Terminator for destroying weed seeds at harvest. Another year of study will solidify results as to whether this add-on equipment makes economic sense for farmers.

The practice of using a hammermill originated in Australia more than a decade ago. The country historically had problems with herbicide-resistant weeds, particularly ryegrass, that were no longer controlled with chemical options.

Missouri has 14 weed species that show resistance to today’s herbicides, and resistance to multiple modes of action are increasing. To combat weeds and protect the future of chemical technology, Bradley and Winans are looking to other options such as the Seed Terminator.

Crush weed seeds

Last year, Bradley asked soybean farmers to allow the university to harvest fields and assess the validity of the tool. Four mid-Missouri farms were selected. The fields ranged from 30 to 60 acres in size.

The study used a Case IH combine outfitted with a Seed Terminator. “We are harvesting these fields just as a farmer would and collecting samples from plots, comparing the seed terminator being on or off,” says Winans, who led the project.

He looked at the samples to determine how much seed came out of the back of the combine and what percentage of the seeds were damaged and would not be able to germinate. Data from two locations, one in Boone County and another in Montgomery County, show that more than 98% of the weed seed is going to be damaged and can no longer germinate, Winans says.

SEED REDUCTION: The table above shows the results of the Seed Terminator at two Missouri locations in 2019. It found weed seed viability reduced.

Much of the data focuses on waterhemp seed. The study concludes that if more than 50% of the seed coat is gone, or the seed is less than half the size of a nondamaged seed, it is deemed damaged. But the Seed Terminator likely will have success on other weed seeds.

Waterhemp is small, 3 millimeters in size or about the size of the tip of a lead pencil. Winans says almost any weed seed is going to be bigger than waterhemp. “If you have velvet leaf foxtail or morningglory, for example, it's going to be ground up in a dust and can be no longer viable for seasons to come,” he notes.

Machine missteps

The Seed Terminator is not a foolproof. “Our initial findings from the 2019 harvest show that there's going to be some degree of header loss,” Winans says. “When the combine header comes in contact with the velvet leaf, the seed falls to the ground before it ever makes it through the combine.”

Although the amount is minimal compared to what makes it through the combine, he says, it's important for farmers to realize the machine is not perfect.

Winans also found a minimal amount of thresher loss. “Not all the seed is directed through the Seed Terminator,” he explains. However, when the chaff comes out the back, he says the amount of seed in it “very minimal” compared to what makes it through the seed terminator.

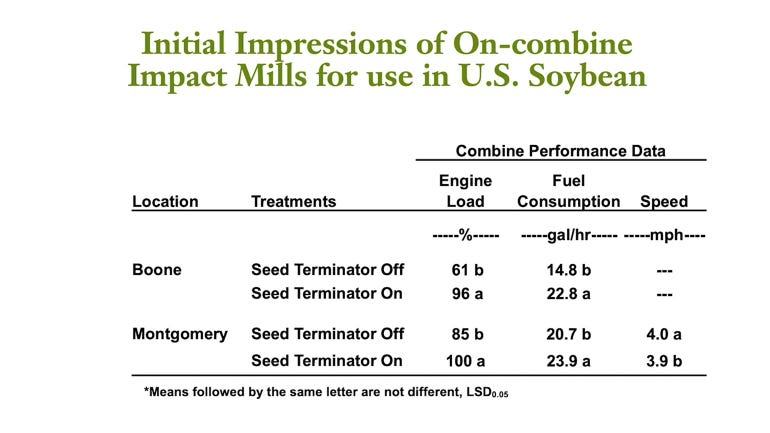

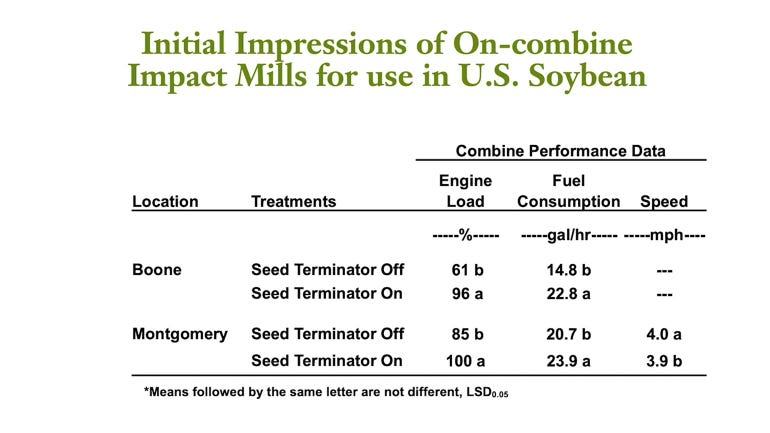

ENGINE NEEDS: The Seed Terminator requires additional fuel when in use.

Like many add-ons to machinery, the Seed Terminator is a drag on the combine engine.

“There is going to be a higher engine load percentage whenever the Seed Terminator is on,” Winans says. The data also found when the Seed Terminator was on, the combine used more fuel per hour. However, engine performance was not affected by a difference in harvest speed.

Winans says these are only the initial results from 2019 harvest. MU plans to continue this Seed Terminator research this year.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like