August 19, 2019

If you have eyes or ears, there’s a good chance you’re aware of last spring’s Green New Deal proposed by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Sen. Ed Markley, D-Mass. Simultaneously broad and vague, it’s a resolution to battle climate change that includes changing the U.S. food system.

Please note neither of its authors exactly hail from farm country.

Agriculture’s response to the Green New Deal was immediate and damning, particularly regarding an FAQ document from Ocasio-Cortez’s office that mentioned cow flatulence as a problem. Her staff later denounced their own document, but Ocasio-Cortez admitted part of the Green New Deal does indeed include reducing “factory farming.”

Much of ag Twitter lost its mind over the cow farts stuff, and farmers there wrote off the entire resolution as little more than another pile from the business end of a cow.

I wish it were that simple.

In a year like 2019, it’s tough to be a farmer arguing against the existence of changing weather patterns — also known as climate change. On our western Illinois farm, for example, April and May were marked by rains of 2 inches and more. Deluge after deluge. It kept up until we got 5 inches in two major storms around the Fourth of July. Then it quit. For five weeks, we got little more than a couple tenths.

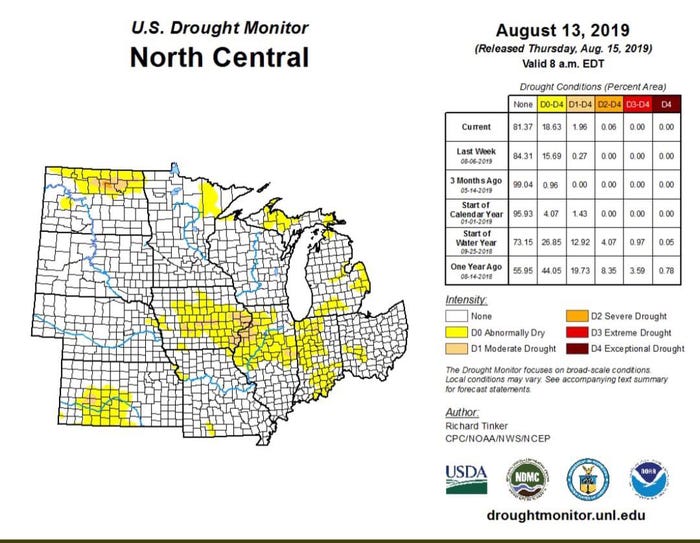

The great irony of 2019 is that after a historically wet spring, parts of nearly 40 Illinois counties are now flagged as abnormally dry or in moderate drought on the national Drought Monitor map. It’s bad enough in seven counties that the Farm Service Agency opened up Conservation Reserve Program ground for emergency haying and grazing in August and September.

Eric Snodgrass, who studies weather patterns for Nutrien Ag Solutions, called this change more than a year ago. Weather patterns suggest we’ll still get our 40 inches of annual rainfall — not in an inch at a time, but in major rain events followed by longer dry spells. Over the past 40 years, Illinois has seen the average frost-free season length grow by 10 to 20 days. The growing season is a month longer in the Dakotas, and they’re growing soybeans instead of barley.

So here’s what we know: Our climate is changing, right here on the farm. What we don’t know: What to do about it — and how to manage what everyone else wants to do about it.

Specifics

The Green New Deal calls for a “10-year national mobilization” to “eliminate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector” by “supporting family farming,” “investing in sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health,” and “building a more sustainable food system that ensures universal access to healthy food.”

You know as well as I do those are goals, not plans. They’re intentionally vague because if AOC can get the culture on her side during a time when the Green New Deal doesn’t have a prayer of passing the Republican-led Senate and White House, she might build enough cultural support to get it done when a new administration comes to town.

The cultural will to respond already exists; it’s simply waiting on the political will to legislate. That means we need to be part of the conversation.

Last week, Rep. Cheri Bustos, D-Moline, introduced her own plan for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, calling it the Rural Green Partnership (read it; it’s not long). She grew up in an extended farm family and has a reputation for listening to farmers. She acknowledges that ag contributes 9% of all greenhouse gas emissions — the least of all economic sectors. But we’re removing more carbon dioxide than we’re generating, offsetting 11% of emissions. She offers up the following specifics:

more money for precision ag and conservation measures that increase soil carbon and reduce runoff

more technical conservation experts

streamlined conservation program sign-ups

more incentives for energy efficiency

more research money for crop breeding, precision ag and soil health

guaranteed broadband access on all farms

The devil may well be in the details — particularly in how to pay for it all — but Bustos deserves credit for getting us in the conversation. She told me at the state fair last week, “I want to make sure rural America is part of the conversation and that ag is viewed as being part of the solution, not part of the problem.

“We can’t be left behind. We’ve got a lot at stake in rural America. And if we’re not part of those discussions, coastal people might not think of us. I want to make sure we’re thought of.”

Bustos has submitted her plan to the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, which will weigh it with the other ideas out there (shortlist of politicians with plans includes Elizabeth Warren, Beto O’Rourke, Kirsten Gillibrand). The committee will come up with policy the House will actually vote on.

Here’s the thing, friends: Bustos is the only Midwesterner in senior leadership in the House Majority. Legislation will ultimately be written to address climate change, regardless of our beliefs or motivations. I’d rather have a seat at the table and be able to explain how potential solutions will affect me and my farm than be complaining from the next room over.

It’s time for agriculture to be part of the conversation. We may not be breaking the planet, but we sure could help fix it.

Comments? Email [email protected].

You May Also Like