The wintertime drought footprint looks worrisome in many areas, but the silver lining is that no crops are being planted in the central U.S. just yet. Still, the current situation will be important to monitor as winter rolls into spring.

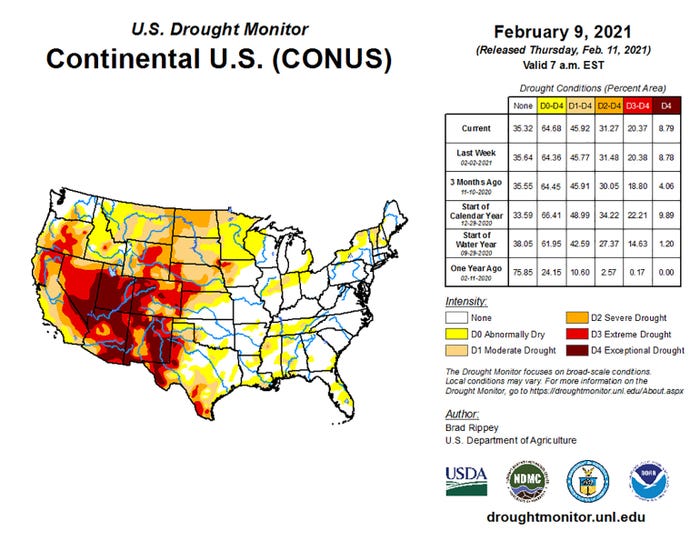

Through February 2, data from the U.S. drought monitor showed 64.4% of the country was affected by some level of moisture deficit, ranging from D0 (abnormally dry) to D4 (exceptional drought). That’s slightly below the worst seasonal levels, but the country has consistently been covered by at least 60% since last September.

The Western United States has been hammered the hardest throughout the fall and winter months, but the Midwest and Plains haven’t been totally spared. In the Midwest, 37.7% of the region was affected through February 2. The worst areas include western Iowa, Minnesota, and a band stretching through central Illinois and northern Indiana.

The High Plains is much worse off, meantime. Through February 2, 93.1% of the region was affected – pretty much everywhere except southern Kansas was facing moderate to severe problems.

A year-over-year comparison shows a stark difference between the start of 2020 and this year so far. At the same point last year, just 25.7% of the country was affected by drought, with virtually no problems in the Midwest or Plains in early February.

The current situation begs the question – when is it time to start worrying?

That largely depends on where you farm, notes Dennis Todey, director of USDA’s Midwest Climate Hub in Ames, Iowa.

“The eastern part of the Midwest is in relatively decent shape starting the growing season,” he says. “There is a band of dry soils running from eastern Missouri to southern Michigan, but we still have expectations of a more active pattern before spring planting that will reduce problems there.”

But from western Iowa into the Plains, more wet weather will be needed to overcome current conditions, Todey adds.

“We would expect to get some precipitation in these areas before planting,” he says. “But the soil moisture deficits are unlikely to be removed by then, so the outlook there is less optimistic.”

One winter wildcard is snow covering the ground in northern states. Through early February, a large portion of the Northern Plains and upper Midwest was sitting under several inches of snow.

“That will need to melt and infiltrate into the soils to allow utilization by crops later on,” explains Brian Fuchs, climatologist with the University of Nebraska’s National Drought Mitigation Center. “This is hard in the winter due to frozen soils and infiltration is minimal.”

With a mild La Niña still in effect, Fuchs is also watching the southeastern U.S. for possible drought development.

A look at NOAA’s three-month outlook for April, May and June, meantime, shows seasonally wet weather could be likely for the eastern Corn Belt and Ohio River Valley, driving home Todey’s assertion that areas farther east may be in better shape by the time planting season begins. But to the west, NOAA largely predicts an equal chance for either overly wet or dry conditions this spring, which may spell an uphill battle for producers in those areas.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like