Most herbicide labels warn farmers not to apply herbicides during a temperature inversion. However, there is little research on inversion with respect to agriculture.

When University of Missouri weed scientist Mandy Bish went searching for temperature inversion research, she found data based on 1960s pollution work. So over the last two years, she's studied and collected information about temperature inversion in Missouri for farmers, companies and government agencies.

Here are eight things about temperature inversion based on University of Missouri research you should know now.

1. What it is a temperature inversion?

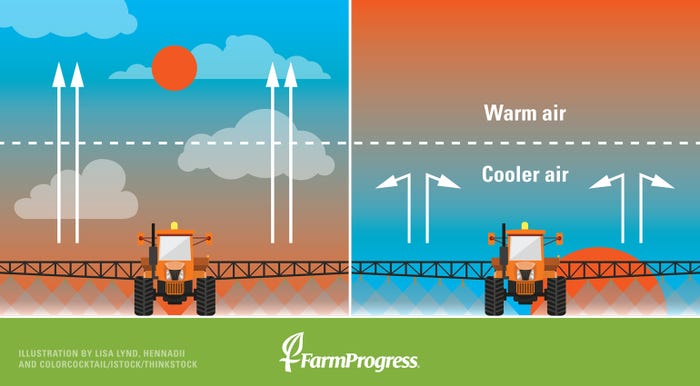

On a typical day, cumulus clouds fill the sky as the sun radiates energy to the earth and warms the air. Warm air rises, because it is less dense. With warmer air rising, cooler air drops, is warmed by the earth and then rises. "It is a constant shuffling of air," Bish explains. "We feel this, because wind occurs."

An inversion happens when the sun sets and is not warming the earth's surface. The cool air sinks, the air shuffle stops, there is no wind and the cumulus clouds dissipate. Now, the cool air is trapped on the bottom.

2. Why is inversion a problem?

Warmer air temperatures near the earth's surface allow volatile compounds to dissipate into the upper air levels. The problem with an inversion scenario — where cold air is trapped near the earth's surface — is that it is very stable. "So when the air is not mixing, any particles suspended in that air stay suspended in the air," Bish says. "If you have particles suspended in the air and you have a horizontal wind gust come through, it is going to push those particles somewhere else." Think smog in a city.

3. When is the most likely time for a temperature inversion?

Last year, in June and July, inversions started at 6 p.m. and continued until 7 p.m. "That was a little bit alarming, because it is still daylight out," Bish says. "The wind has died; it seems like a pretty good time to apply herbicides." But it is not.

This year is showing that inversions last longer. For example, in June, there were 12 temperature inversions reported in Columbia, Mo. Eight of those lasted from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., Bish says. Most are lasting more than eight hours.

4. Does wind speed indicate inversion?

For the past two years, Missouri weather data recorded wind speeds every 3 seconds in March, April, May, June and July. Combining all of the data, Bish looked at where inversions occurred, and how often, at that inversion, the wind was speed less than 3 mph. "Over 90% of the time in June and July, when you have an inversion, wind speeds were less than 3 mph," she says. "That is why we think wind speeds are an indicator of a temperature inversion setting in."

5. Where do most temperature inversions form?

Some farmers believe inversions happen only in valleys. There is a type of inversion that can happen specifically over a valley, Bish says, but really, anyplace where the sun can hit the earth's surface can have an inversion.

Temperature inversions can also form, break up and reform in the same location in a matter of hours. "We had a crazy event on June 20 where an inversion formed, a rainstorm came through, it broke it up, then it came right back," Bish says. "So we are still learning a lot about these."

6. How locally restricted are these inversion?

Temperatures vary around the state, causing inversions to occur on different dates. However, in Missouri the entire state experienced inversion on the same day last month. "There were a couple of nights [June 24-25] with clear skies and calm winds across the entire state," Bish says. "In every area we were monitoring, there was a temperature inversion those nights."

There are localized inversion events. One location had temperature inversions three nights in one week. Then the next week, the same location saw cloudy skies and rain and not many inversions. "So, sometimes they come in chunks," Bish warns.

7. Can you track or predict a temperature inversion?

Predicting temperature inversion is tricky. There are tools for farmers that record soil temperature and relative humidity, but not many for inversion potential, according to Bish. The University of Missouri has developed a real-time temperature inversion monitoring website for real-time temperature inversion monitoring.

The site reports air temperatures from eight Missouri locations. On the home page, a state map displays locations, along with a blue arrow. A downward arrow means there is likely an inversion, an upward arrow means there is likely not an inversion. Along the left-hand side of the page, there is a links to graphs and charts that include inversion, temperature and wind speed.

Another tool that may help predict temperature inversion is Agrible's Spray Smart phone app. The tool provides real-time data for inversion risk, atmospheric conditions, wind direction and wind speed.

No access to internet or website? Bish says to step outside. If it is a clear sky with no wind or cumulus clouds, it is the right atmosphere for an inversion.

8. Do smoke bombs work as a test for inversion?

Some herbicide labels say use a smoke bomb to see if there is an inversion. The University of Missouri tested the theory. Researchers lit off a smoke bomb at 4 p.m. when there was no inversion. The smoke dissipated within 50 seconds. Then they set one off at 7 p.m. The red smoke lingered well beyond a minute, indicating inversion. Bish says smoke grenades can validate an inversion, but more work still needs to be completed.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like