January 16, 2018

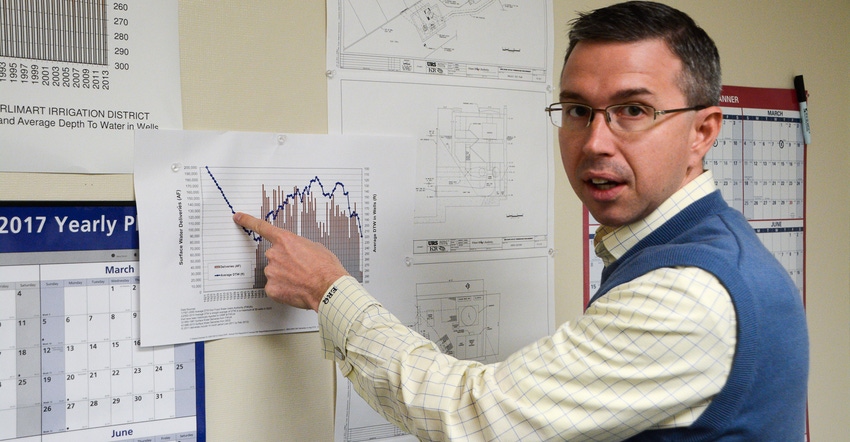

A central California irrigation district will build a new water bank in an adjoining district to bolster groundwater supplies and help reduce subsidence, which caused a 60 percent reduction in delivered capacity in the Friant-Kern Canal.

Delano-Earlimart Irrigation District (DEID) hopes to have a 30,000 acre-foot water bank in neighboring Pixley Irrigation District (PID) complete by the end of 2019. The plan is to use surface water from the Friant-Kern Canal in surplus seasons to bank water in the aquifer under DEID’s northern neighbor and draw on those supplies in dry seasons.

Under the agreement with Pixley, 10 percent of water deposited in the water bank by DEID will be left behind for PID use.

DEID has two water contracts with the Bureau of Reclamation – a firm supply of 108,000 acre feet, and wet-year availability to capture an additional 74,500 acre feet. This water comes from Millerton Lake near Fresno.

Planning for the estimated $50 million project has taken about 10 years, according to Eric Quinley, general manager of DEID. The goal is two-fold: help PID farmers replenish their aquifer and provide an additional water bank for DEID. Funding for the project will come from a federal grant related to the San Joaquin River Restoration and through the sale of water banking shares.

Both districts use a combination of surface water and groundwater to irrigate crops in the region, though PID is much more reliant on groundwater for its crops, which range from almonds to dairy forages. While PID has access to 31,200 acre feet of surface water from the Cross Valley Canal, Quinley says availability is scarce because it must first come through the Delta from northern California.

“They experience more challenges than south-of-Delta federal contractors because they’re last in line to get their water moved,” Quinley says.

For DEID, the crop make-up is largely permanent plantings. Half of the district’s 56,500 acres of irrigated land is planted in table grapes with significant acreages of pistachios and almonds. It recently annexed 7,500 acres of previously-unregulated lands for purposes of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

The district has groundwater banking assets in its own Turnipseed Water Bank, and by deposit in two nearby districts. Quinley says DEID has been “dutiful” in its effort to protect aquifers and prevent subsidence.

Canal subsidence

Early last year surveys revealed five inches of additional subsidence in an area of the Friant-Kern Canal just upstream from where DEID gets its surface water. That happened over a five-month period in early 2017 which choked water deliveries to DEID and districts to the south by 60 percent. Until repaired and restored to designed capacity, this will limit water available to growers and the water bank DEID and PID will build.

The problem with subsidence is once the aquifer collapses upon itself “you don’t get that capacity back,” Quinley says.

Not all farms in the southern San Joaquin Valley are served by canals and surface water.

This makes surface deliveries even more critical for districts like DEID. Last year DEID had used excess runoff from the Friant-Kern Canal to recharge aquifers. In its newsletter and through other communications the district told growers to turn off wells and take what water they could from the system to maximize groundwater recharge.

With the subsidence comes the need for costly repairs to the Friant-Kern Canal and questions of who pays for those repairs. While the Friant Water Authority says it will seek federal funds to repair the Central Valley Project system, Quinley worries that districts in the system will be forced to pay if federal funds are not available.

Whether the downstream districts directly affected by subsidence will foot the bill, or if districts across the entire Friant system will share in the cost is a question Quinley says has not been answered. Nevertheless, Quinley says restoring water deliveries to their designed capacity within the canal is critical.

“In our opinion Friant Water Authority needs to do whatever it takes to restore the capacity of the Friant-Kern Canal,” Quinley says.

You May Also Like