"The worst thing we can say when something changes is we didn't see it coming," says Ronnie Hopper.

For Hopper and many other irrigators on the High Plains of the Texas Panhandle, things have changed drastically in the last 50 years — and will continue to change, he says.

"If you were to plot on a graph the number of farm families in my community over a 50-year period, that slope is going down. If you were to plot the number of acres under tillage in the last 50 years, there's less now than 40 to 50 years ago. The amount of water pumped for agricultural use is going down. The number of on-site landlords is going down, too," says Hopper, who farms near Petersburg, Texas. "We need to recognize what's happening around us."

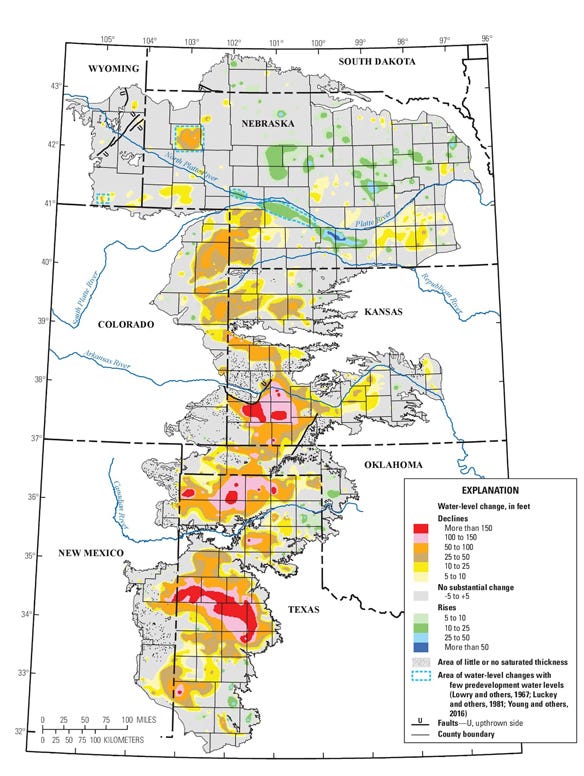

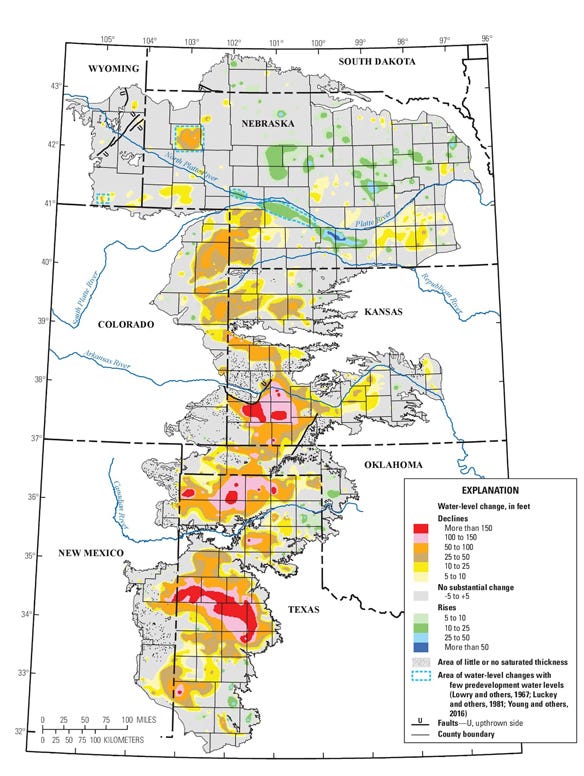

The Ogallala Aquifer underlies about 174,000 square miles and eight states on the High Plains. For reference, that's an area roughly the size of Colorado and Oklahoma combined.

VALUED RESOURCE: This map shows the water level on the High Plains Aquifer from predevelopment to 2015. The Ogallala Aquifer underlies about 174,000 square miles and eight states on the High Plains.

The Llano Estacado region of the Texas Panhandle has a population of around 1 million people — most living in the metropolitan areas of Amarillo, Lubbock, Midland and Odessa. While rural towns are experiencing depopulation, the total population of the Llano Estacado region has been stable overall. However, metropolitan areas throughout Texas continue to grow.

"Those small towns are in the process of depopulating. Some of that population is moving to Lubbock and Amarillo. A good portion are moving off the High Plains to Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin, Houston," Hopper says. "They claim 1,000 people are moving to Texas every day."

Those population centers have a high demand for water. Municipalities like Amarillo and Lubbock have, on several occasions, purchased thousands of acres of land for access to water rights. As water requirements for these municipalities rises, it means less water available to irrigated agriculture, although saturated thickness of the aquifer varies by location.

This, combined with groundwater declines and variable saturated thickness of the Ogallala Aquifer, are challenges faced by many in the High Plains. So, it's even more important to use the water available in a more economical way. A grower panel at the recent Ogallala Aquifer Summit in Garden City, Kan., weighed in on this ongoing challenge.

Moving up adoption curve

One of the first steps is determining the value of the water applied, and that comes from its consumptive use. This means determining beneficial and nonbeneficial consumptive uses.

Technology plays a role here, including the use of flowmeters, soil moisture probes, weather station data tools and devices measuring evapotranspiration (ET). These tools are key to understanding the full water budget within a field by establishing how much is available to begin with, how much is used by the crop, and how much percolates into the ground and is returned to streamflow.

However, adoption of technology is often a slow process, notes Darren Buck, who farms in Morton County, Kan., and Texas County, Okla.

"The biggest challenge is making sure your farm and what we're doing is the most efficient we can be. I used to think I was pretty good at it. The more I learn, there are probably other things we could do to help — like using technology to monitor soil moisture, and coupling it with weather and forecast data so we can truly dial in and give the crop what it needs," Buck says, adding, "We're barely registering on the adoption curve."

To encourage quicker adoption, Roric Paulman, who farms near Sutherland, Neb., envisions a kind of "Master Irrigator" program offering different curriculum for training irrigators on using soil moisture probes, weather stations and any other water-related technologies, as well as serve as a kind of certification process for participants. So, a certain level of training would qualify irrigators to use a given amount of water, based on the watershed they are located in.

"Adoption and innovation has been at a rapid pace, but adoption beyond early innovators and the challenges that face that next group of producers is the next step. That's 40% to 50% of the adoption curve. How do you reach that?" Paulman asks. "You'd have a base, and if you complete a certain level of education, you're allocated this much more water. Then you incrementally come to a cap, eventually reaching the master level. When you achieve that, it's like ongoing professional development."

This certification process could also be used to track production of certain commodities, and add value to the products being raised, earning a premium for growers.

"This is where we're heading with the consumer mindset," Paulman says. "If you underpin it with a certification process, it's just like certified pesticide-free, or non-GMO. Why wouldn’t we certify our water use? It's going to come back to us. I think it's going to tie into every piece of the food chain. How do we set the stage for this? Is it an uphill battle? Absolutely."

Diversity brings opportunity

Optimizing the value of the water available means something different depending on the location. In some cases, Paulman notes, assigning water applied to its highest value means growing value-added crops.

"I admire my friends and neighbors for growing corn and soybeans out here, but with the cost of energy, a good dryland quarter will still net better out here today," he says. "What we have is the ability to apply just in time, and variable-rate and all those tools. But if you don't have a crop that returns some value to that, all I'm doing is the same thing I've always done in looking at ways to reduce inputs on a bulk commodity."

Crops like yellow field peas have grown in acres in Nebraska. Other less water-intensive crops include popcorn and grain sorghum. In Texas, Oklahoma and southwest Kansas, irrigators have started growing cotton, which uses less water than corn while still creating value. In places like the Texas Panhandle, split-pivot irrigating has been used to grow crops with different pollination periods — sometimes two separate maturity corn hybrids, or a split between corn and a drought-tolerant crop like cotton.

One option Buck has advocated for is industrial hemp, which is still in its infancy.

"Hemp is a drought-hardy crop, and it could have value," Buck says. "There's another example of looking down the road of what might be an alternative crop that might have value. It's going to take quite a bit of time to develop market or processing, because we haven't been in the market for decades."

Soil health practices like no-till and diverse crop rotations also play a role. This includes building soil organic matter and water-holding capacity, as well as planting crops with lower water demands.

"We get about 18 inches of annual rainfall. Generally, those rains are pretty violent. If you can improve the infiltration rate and water-holding capacity of your soil, that's a good thing you can catch more of those rains," Hopper says. "We know we're going to be pumping less water from the Ogallala moving forward. That makes it even more important to ensure we can maximize the potential of the rainfall we have."

Kyle Averhoff, manager of Royal Farms Dairy near Garden City, notes in addition to minimum till, no-till, diverse crop rotations and residue management, they're also returning nutrients to the land while reusing water. For Averhoff, water quality is just as important as water quantity.

"We try to add value to the water. Being a livestock operation, we're fortunate to be able to enrich our water with nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. At our home dairy, we're connecting into around 23 different systems with effluent water. We can maintain very high organic matter levels in our soil," Averhoff says. "We're also raising crops that can maximize our dollars per acre inch of water, and we work with different rotations in our forage program that maintain residue and organic matter in the soil. All of those things are important to being stewards of how we use water."

Boosting rural viability

With diversity also comes opportunity for new markets and jobs. Averhoff says for communities to function, people are needed — and those people need employment.

"At the end of the day when you take away how much we re-irrigate in our dairy, it's plus or minus the water use of one circle of corn," Averhoff says. "But we employ a lot more people than an irrigated circle of corn, pay more property tax and put more kids in school. That's the benefit. Livestock, whether dairies or feedyards, bring a lot of families and children into local communities and school systems. It brings a higher value, a more competitive market to your choices when you're raising crops."

According to the 2012 USDA Census of Agriculture, irrigated farms contributed about 39% of U.S. farm sales. Farm sales for Western irrigated farms — including Nebraska and Texas — averaged $513,272 per farm, over four times the average for Western dryland farms. That's why it's important to maintain the long-term viability of the resource, Buck says.

"Irrigated agriculture creates so much value," Buck says. "My head farm manager is in the top 25% of paid people of this community. He works hard and he earns it, but he earns good money. He has health insurance, a pickup to drive, a cellphone, and makes a solid wage. He makes well over the median and average wage in the U.S. That would go away without irrigation. That impacts families. You multiply that by thousands of irrigated acres just in Texas, Cimarron and Morton counties, that's a huge deal."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like