Texas potato growers have been waging war on a tiny potato psyllid ever since its arrival from across the Rio Grande River in Northern Mexico in the early 1990s when a disease known as papa manchada, or more commonly referred to as the Zebra Chip (ZC) disease, hopped a ride into Texas, Arizona, Colorado and other Southwestern states, bringing millions of dollars in damages to U.S. commercial potato crops in the ensuing years.

In addition to the risks for potato producers, USDA researchers later correlated the presence of the tomato-potato psyllid Bactericera cockerelli, which infests both potatoes and tomatoes, to the presence of Zebra chip. Scientists soon learned that by targeting the suspected host psyllids with neonicotinoid insect control measures, an effective management program could be and has been developed.

In recent months however, Dr. Ada Szczepaniec, a Texas A&M Assistant Professor and entomologist in Amarillo, has been working to help identify and implement new methods of management and treatments for controlling these psyllids, which according to the latest reports, have been able to develop resistance to neonicotinoid-based insecticide management programs.

Now she is warning that new, future and alterative management and control programs are needed and must be used to combat what is apparently a growing neonicotinoid treatment resistant problem that further threatens heavy economic losses to U.S. potato and tomato crops.

COMMON PEST

To complicate this latest development, these psyllid are so common now in parts of Mexico, especially around Saltillo, where the psyllids were first detected in the late 80s and early 90s, resistance problems have surfaced further west across the U.S.-Mexico border and threaten to migrate to other areas in the United States.

The latest reports indicate resistance problems have already been reported in agricultural-rich production areas in Texas, and further movement is expected in the years ahead.

For the latest on southwest agriculture, please check out Southwest Farm Press Daily and receive the latest news right to your inbox.

The latest reports have been filtering in from the heavy potato growing region of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley. From here, they have spread north into the Winter Garden region of Southwest Texas and eventually into the potato fields of West Texas and the Texas Panhandle.

Researchers working on the genome of the psyllids say they believe though early reports suggested the cause of Zebra chip might be the bacteria Candidatus Liberibacter, studies have not been able to consistently associate any phytoplasmas with the disease, and they say the tomato psyllid also carries the pathogen and infects commercial tomato crops in Texas and across the Southwest as well, and could continue to spread north in the years ahead.

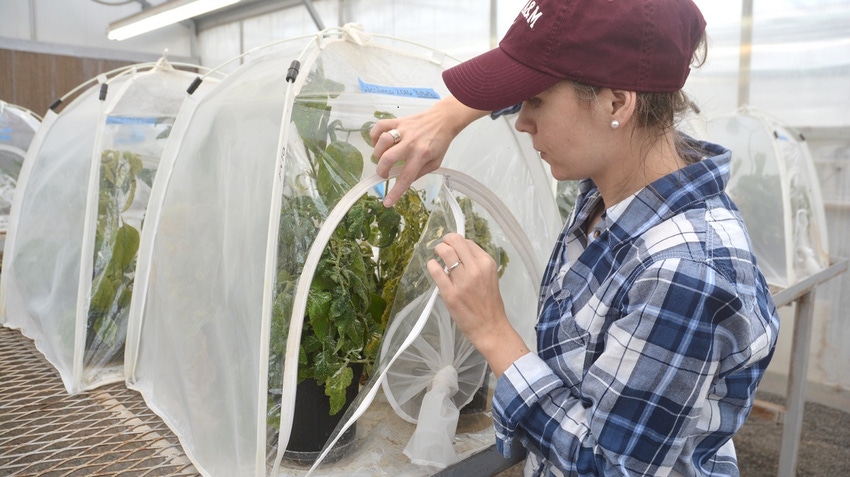

Szczepaniec has been capturing these infected, resistant psyllid varieties and has been intentionally moving them to potato and tomato greenhouses in the Amarillo area in an effort to determine resistance levels of the insects and to develop new insecticide treatments that could be used to control them.

"The problem we are seeing is the aggressive use of the neonicotinoid product in Mexico has allowed the psyllids to develop a resistance over time to the insecticide, and we are in need of developing alternative treatments that would prove effective as these existing controls fail," she said.

"When the neonicotinoids work, they work really well. They can be used during planting and are taken up by the plant and can be found inside the plant tissue. So when the insects feed on plants treated with the insecticide, they die," she says.

But other formulations of these insecticides can be sprayed onto the crop after it emerges, offering new and possible future treatment methods.

"We are seeing some resistance to neonicotinoid control measures, especially in the Valley now, so some populations of psyllids are no longer effectively controlled by these neonicotinoid insecticides. This has not been confirmed experimentally until now, and this is one of the priorities of our current research program.

“We want to figure out what producers can use if neonicotinoids are no longer effective in their region,” she said. “We will continue testing and collection over several years in order to provide producers with customized combinations for their regions where we collected the psyllids and help them manage them successfully.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like