Today’s tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from the European Union, Canada and Mexico puts billions of dollars worth of U.S. ag exports in jeopardy. While today’s news is bad for farmers, the bigger concern may be what’s next in the China-U.S. trade negotiation. The administration announced it’s moving ahead with tariffs on China and will have a list of targeted imports by June 15.

What’s driving the protectionist stance in the White House?

Start with the key players in the administration’s trade team. On one side are the trade hawks – the folks who’d like to blow up the WTO and start over. That includes Director of Trade and Industrial Policy Peter Navarro, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer.

On the other side you have Director of National Economic Council Larry Kudlow, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Steve Mnuchin, and USDA secretary Sonny Perdue.

The trade hawks have gotten the president’s ear because Trump talked tough on China during his presidential campaign. They believe that China has for years been abusing international trade mechanisms and, as a result, are ripping off Americans. Navarro even wrote a book about it: Death by China: Confronting the Dragon – a Global Call to Action.

“They believe we’ve been at war with China over trade for decades,” says Mark Duval, immediate past President of the American Chamber of Commerce in China. “These folks believe the war has already been lost.”

Historical efforts to negotiate with China on industrial policy issues have been ineffective, so it’s time for a new approach – even if it means making life uncomfortable for U.S. consumers.

The trade hawks have two goals: one, insulate the U.S. economy from China’s behavior and two, punish China for some of its unfair trade efforts.

The story dates back to shortly after Trump’s inauguration when he began meeting with the hawks, looking at ways to get China back to the bargaining table.

‘Thoughtful and secretive’

“While they do reach out a lot to stakeholders and policy people, this group has been thoughtful and quite secretive, trying to come up with something that will work within the U.S. legal and international (trading) system,” says Mark Duval, who previously served as president of the American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China.

“The Chinese government is convinced that China is on the rise while the west is in disarray and decline,” says Mark Duval, immediate past President of the American Chamber of Commerce in China. “They see Trump as a paper tiger and believe they have all the leverage.”

“They don’t share a lot, but they’re doing a pretty good job trying to figure out a way to change the system,” he adds. “Despite the drama you see in the rest of the Trump administration, this group has been very careful and methodical.”

In January Trump took a new approach by slapping anti-dumping tariffs on solar panels and washing machines; sorghum farmers paid the price. Why is that relevant? Years ago President Obama began an investigation into China’s trade policies in those industries, but backed up for fears it would offend or provoke China. In that situation it was American chicken farmers who paid the price. Reading those case histories may be instructive for the Trump team.

Trump bases his strategy to charge 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports on Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which gives the executive branch authority to investigate impacts of trade on national security. Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, Trump would impose a 25% tariff on $50 billion of goods imported from China containing industrially significant technology. China threatened retaliation, cooler heads prevailed, and the two sides sat down to negotiate - for a while, anyway.

China reverses course on economic reforms

China began to modernize its economy under Deng Xiaoping as far back as 1978. More sweeping changes went into play leading up to 2001 when the country joined WTO. But since 2005 China’s economy began fundamentally shifting back toward heavy government control, which is less WTO-compliant. After the global financial crisis in 2009, the state poured trillions into the economy and directly into State-Owned Enterprises, even after many had been dismantled - and that’s what has U.S. leaders worried.

“From our side of the fence when you look at the impact of China trade policies and their impact on the world, you start to see where the trade hawks are coming from,” says Duval. “The hawks have been arguing they shouldn’t even be in WTO because of the way they have backed away from adopting a market driven, western-like economy.”

In a centralized economy where elections and votes don’t matter, economic planning can be a powerful tool. According to China’s 2005 medium and long term science and technology development plan, the country’s goal is to be self-sufficient in 11 key sectors, including agriculture. It’s a top down national strategy where implementation requires the mobilization and participation of all sectors of society. The plan defines import substitution achieved by leveraging state resources and regulatory systems – regulations that are blatantly unfair to foreign-owned companies. It promotes Chinese enterprises that will dominate domestic markets, and be internationally competitive as well.

In other words, a plan to take over the world. And we’re only half kidding here.

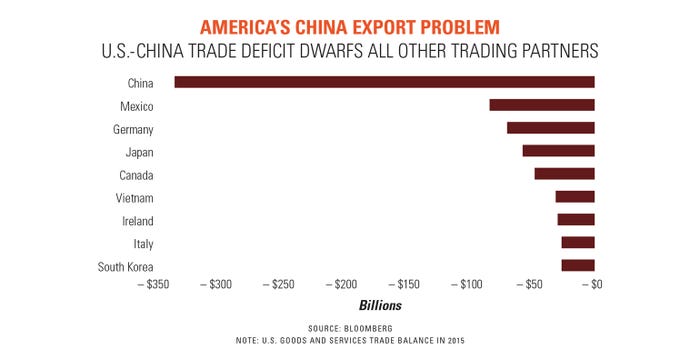

More recently, the government has outlined a three-part plan building on a Made-in-China policy; the first period (until 2020) is aimed at comprehensively building a moderately prosperous society and eliminating poverty. After the second period (2020-2035), China expects true socialist modernization, and by the end of the third period (2035-2050), China will finally become a leading nation in terms of national power and global impact. Trade hawks argue that many of those policies will accelerate the existing U.S.–China trade deficit - $375 billion and growing.

Made in China 2025

The country’s ‘Made-in-China 2025’ policy could certainly make that deficit even bigger. China makes a lot of everything but most production is low value, heavily polluted, and not in industries of the future. Through this policy China plans to upgrade its entire industrial base, focusing on 10 key industries (see table).

“That goal is not the problem,” says Duval. “It’s the tools and methodology they could use to get there. The strategy includes stealing technology, subsidizing local companies and limiting market access to foreign companies. “The methodology for this policy will end up shutting us out and that’s what has everyone alarmed.”

As this Bloomberg story explains, Trump wants tariffs on $50 billion worth of imports from China as punishment for the alleged theft of American intellectual property. Such violations, from counterfeiting famous brands and stealing trade secrets to pressuring companies to share technology with Chinese companies to gain access to China’s vast market, have long angered China’s overseas competitors. The U.S. and European Union are China’s biggest trade partners by far, but both groups complain bitterly about a lack of transparency, industrial policies that discriminate against foreign companies, strong government intervention in the economy resulting in a dominant position of state-owned firms, and poor protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights.

Is there leverage?

Will U.S. tariffs be enough to effect change? Duval says it’s hard to say.

“The Chinese people and government are industrious, smart, and able to get things done,” he says. “They have a plan to address their economic and social issues and ‘Made-in-China 2025’ is part of this plan. They’re not going to listen to us when we tell them to change it.”

On the other hand, “These tariffs would be a tremendous threat to their economy,” he adds. “Ultimately you need something that will force them to the table to make changes.”

While China may be a member of WTO, it clearly shows few signs it will play by WTO rules. The only thing China recognizes and respects is power, but China’s two biggest trading partners – the U.S. and European Union, which together purchased 35% of China’s exports in 2017 – must sing from the same hymnbook to force real change.

“Europe absolutely agrees with our industrial policy concerns,” says Duval. “On the other hand they are delighted to sell more to China if China buys less from the U.S. On a political level we have to work through how we dance together.”

To be sure, that alignment could be easier said than done, especially now that the U.S. has slapped some of its closest allies with tariffs.

“The Chinese government is convinced that China is on the rise while the west is in disarray and decline,” says Duval. “They see Trump as a paper tiger and they have the leverage. They see fragmentation in Brussels, dysfunction in D.C., and tariffs on Trump’s base – U.S. farmers -- are easy to apply.”

The good news is, as China’s middle class grows so will its tremendous appetite for international goods, including American goods.

“That gives us some leverage,” says Duval. “But the Chinese will only change if you force them to change.”

In China, everything is possible but nothing is easy, concludes Duval.

“You have to realize you’re dealing with a no trust society, very different than how we often work in the west,” he says. “China starts with zero trust; so if you go in and have a few dinners and make relationships, and think that you are building a business - remember, you can still lose your shirt.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like