September 4, 2018

There’s a rising movement in agriculture, and it’s not political, it’s technological. Advances in sensor tools to measure more than temperature and moisture provide new avenues of data capture for your farm. But how does this tech work? And once you have the information, what do you do with it?

John Burton, CEO of UrsaLeo Inc., a California startup that got rolling about 18 months ago, explains that the idea of smart sensors gathering information is “already well-established in the consumer space.” He points to the rise of smart buildings and factories, and says moving those same sensors to a field environment has potential for gathering data you can use for decision-making on the farm.

“There are so many advantages to be able to put sensors in equipment, in fields and in buildings to gather data, and put that data to work to make decisions,” Burton says. “And as you gather more data, you can use more advanced techniques and predictive analysis to make decisions with that information.”

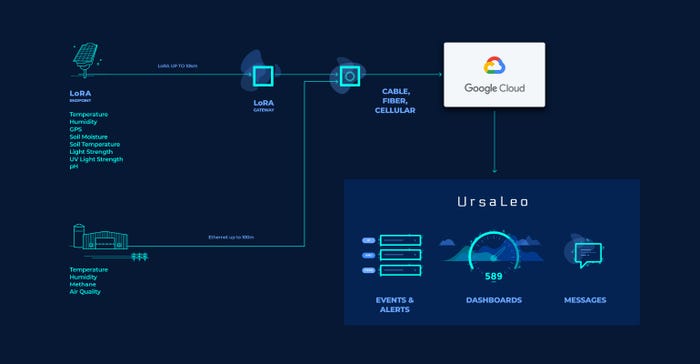

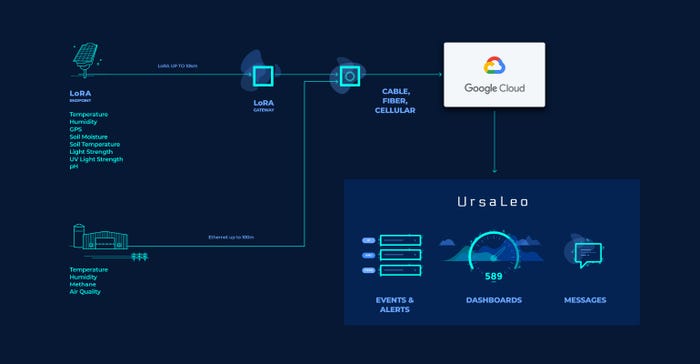

UrsaLeo has developed what’s called an “internet of things” system that provides sensors and the means for taking that information and getting it to the cloud where it can be accessed by farmers, or by programs farmers use for making decisions. The key is this concept of the internet of things (IoT).

IOT AT WORK: This diagram from UrsaLeo shows how data from the field move to the cloud and into the company’s dashboard, where users can see information. (Image courtesy of UrsaLeo)

What the IoT is, and how can it help

In the past, a sensor in the field was often a stand-alone item. A single weather station might gather temperature, wind, humidity and rainfall information and send information to a computer; or allow the user to “call in” to get automated information from the station.

The challenge is the stand-alone nature of that system. How many of those stations can you have in a field if they don’t connect to a central source easily?

The new sensors that leverage the internet of things can be diverse, and farmers can increase their number in the field. Each sensor uses a network approach to “report” information gathered to a central location that would then move that information to the Web, or cloud, where it can be accessed by other software for decision-making.

The system uses the Google cloud, making the information available to any service that a farmer might subscribe to for data analytics.

However, an initial internet of things application on a farm might very well be a grain bin where temperature sensors in the bin report information; and if the crop gets hotter, or cooler, than desired, the system can alert you to act. That’s not data analytics, it’s tech in action.

Having those sensors at work in the bin gathering that grain condition information could go beyond a simple alert to provide data to fans or other temperature-control devices that can be put to work to manage that grain quality.

One innovation that’s making field-level IoT possible is something called LoRa (Long Range). This is a communication network standard. “In a building where you have easy access to Wi-Fi or wired internet, transmitting the data is relatively simple,” Burton notes. “We have to have a system in the field where there is no power for the sensor.”

Burton explains that LoRa is a low-power, long-range system. “If you transmit information using cellular networks from each sensor, that’s a relatively high-power consumption approach,” he says. “LoRa is extremely low-power, and each sensor can have a range up to 6 miles or more. This is a better way to get information from the field into a centralized system, or cloud.”

He adds that LoRa works best if you’re not collecting too much data, and reporting it over intervals — say every few hours. The individual LoRa sensor shares its information to a centralized collector, which in turn could use LoRa, a cellular connection, Wi-Fi or even satellite connectivity to move information to the cloud.

Putting it into practice

Angie Sticher, cofounder of UrsaLeo, is an Apple alum who is chief operating officer and chief product officer of the company. She explains that the firm now has a system that includes sensors and a way to get information from field to cloud. “We have a customizable dashboard that a farmer could use to see information as it comes in.”

If you’re just focused on temperature or humidity, the system can send you an alert over text or by email. If parameters being measured are either too hot or too cold, you can take action, she says.

In other ways, UrsaLeo sees putting sensors to work on machines. If you have a piece of equipment where something isn’t working properly, the UrsaLeo system could pull that into this dashboard, and you could be alerted ahead of equipment failure.

Adds Burton: “We love this kind of stuff. We live and breathe all the ‘plumbing’ that ties this together. We don’t plan on going vertical to do the analytics; we just want to be able to capture the information and share to other services easily,” he says. “We have an application program interface that others can use to pull in our information.”

Burton listed a range of ways IoT could be changing your farm life in the future, including:

• tracking air quality for animal safety

• checking on grain condition and storage temperatures

• monitoring manure waste and methane levels

• watching water, fuel and other fluid levels remotely

UrsaLeo already has hardware available for field deployment, and farmers could engage the cloud with some information as a test. How the API connects with other programs would have to be determined on a case-by-case basis. Learn more at ursaleo.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like