December 6, 2018

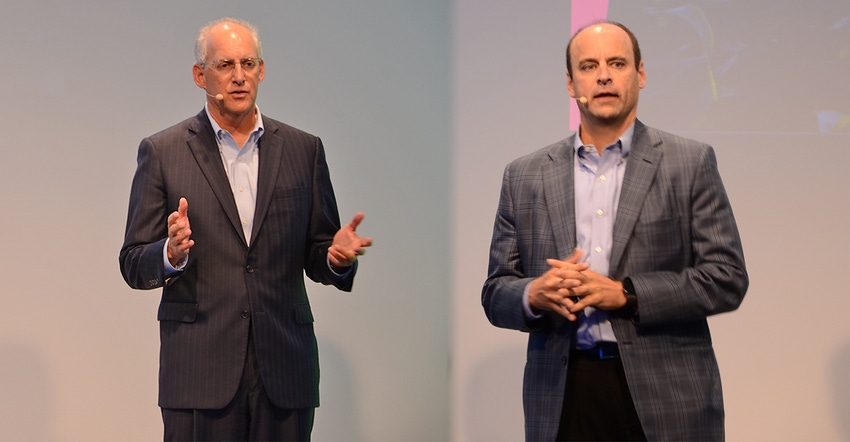

The world of big data gets a lot of attention in agriculture, with the promise of smart programming that takes all the information gathered on the farm and turns it into advice, or other information, you can use. And the market is starting to see that with tools for seed selection, but that’s only a start. Farm Progress talked with James Swanson and Michael Stern recently about the future of digital farming, and learned a bit about what’s ahead — as well as what’s needed for information to be even more complete. Swanson is the chief information officer of the Bayer Crop Science Division; Stern is head of digital farming, Climate Corporation.

The two executives talked a few weeks after Bayer’s acquisition of Monsanto was final during a Bayer Future Farming media event in Germany.

“The geography is bigger [with the acquisition], and both brands are positively known,” Swanson said. “We have the ability to bring data across two sets of companies and bring innovative products to the market for seeds, traits, biologics, crop protection and digital ag tools.”

Stern noted that Climate is now on more than 60 million paid acres in the United States with its FieldView products, both Plus and Drive. The company is covering about 30% to 35% of the corn, soybean and cotton acres in the U.S.

Also early in 2018, Climate expanded into Europe to add acres in that part of the world. “We’ve seen historic growth since we launched FieldView in the United States: from 15 million acres in 2016 to 60 million acres today,” Stern said.

Bayer, before the acquisition, was creating its own digital farming business, which was rolled out at Agritechnica as Xarvio in 2017. That division was later spun off to BASF as part of U.S. Department of Justice requirements regarding competition. Yet Stern sees the digital farming landscape as a series of partnerships.

“For the FieldView platform, we’re looking for partnerships,” he said, noting that billions of dollars have been poured into ag-focused startup companies in the past few years. However, Stern sees Climate leveraging one tool that not everyone has access too — genetic data.

“Genetic data is a very important piece to develop quality algorithms,” he said. Algorithms are programming language used to take information in and turn out useful results. A key example is the company’s recently released Seed Placement Advisor, which will see a commercial launch in 2019 for some parts of the country. The tool will help farmers make precision seed choices for different fields based not only on how specific seeds perform, but also soil information, weather and other factors for that field.

“Having access to grower historic distribution channels — and access to the grower — takes time and trust. And that’s expensive if you don’t have it,” Stern said.

Filling in data gaps

And while Bayer has a vast set of field, weather and genetic data points, Stern pointed out one area where he sees more information could have value. “Soil data is the most relevant gap in what we have,” he said. “Typically, farmers collect a soil sample on 2.5-acre grids every four years.”

However, more precision is needed to match soil information to other data. Stern noted that meter-level accuracy would be more beneficial. One tool he pointed to was the Precision Planting Smart Firmer, developed when Precision Planting was part of Monsanto. “We could get the moisture information from the Smart Firmer into FieldView, and that’s where I think this can go.”

Precision Planting is now part of Agco.

Stern noted that soil is an undeveloped data layer that could have value if captured at planting. “It would be interesting to correlate that information, and we’re going to need more of that type of on implement sensor development,” he added.

And data collection can make a big difference. One area Stern pointed to was hybrid development, noting that, on average, it takes seven years to develop a corn hybrid, and it may be planted on 250 acres during development. But in the first year in the market, if put into on-farm strip trials, the company can see information from 500,000 acres in the first year.

“That’s a larger data set in Year 1 than we ever had in the past,” he said. “And that’s on a more diverse soil environment and geography than ever before.” He explained that adding in Smart Firmer information would allow for advanced correlations of hybrid performance that could be developed with the help of computer algorithms, and even machine learning.

Added Swanson: “We’re working with imputed genomes and simulations on more data. This can progress the pipeline. We can tie to all the data sets that Climate is getting and have new opportunities for innovations. We’re answering questions today that we didn’t imagine just two years ago, and it continues to feed itself.”

The aim is to make a better link between that seed and an individual farm field to maximize yield in the right conditions. It’s a dream for digital agriculture, but one that Climate and Bayer are working toward. It bears watching.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like