A lot goes into figuring out what kind of lighting is suitable for a greenhouse. Much of that depends on what’s being grown, whether it’s flowers and herbs or tomatoes and cucumbers. But it also depends on how much light Mother Nature provides.

Neil Mattson, associate professor of plant science at Cornell University, said proper lighting can allow a grower to get a head start on the growing season and potentially make more money.

It all starts with knowing how light is measured. In a greenhouse, the amount of light coming through is measured in micromols. The total light intensity — measuring all light between 400 and 700 nanometers, the visual light spectrum — can be measured using a quantum sensor, which costs around $550.

“A micromol is telling us how many little packets, or bundles of light, that we get. How many of those packets of light are hitting a square meter per second,” he said at the recent Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Convention. “That’s an instantaneous measurement, and this changes very quickly.”

How much total light a plant gets per day is what’s most important to consider.

“Those little packets of light, you think of them as little droplets of rain,” he said. “What we’re really interested in is setting out a rain gauge, or a rain bucket, and calculating how many droplets of light that we got for that whole day. This what’s called the daily light integral.”

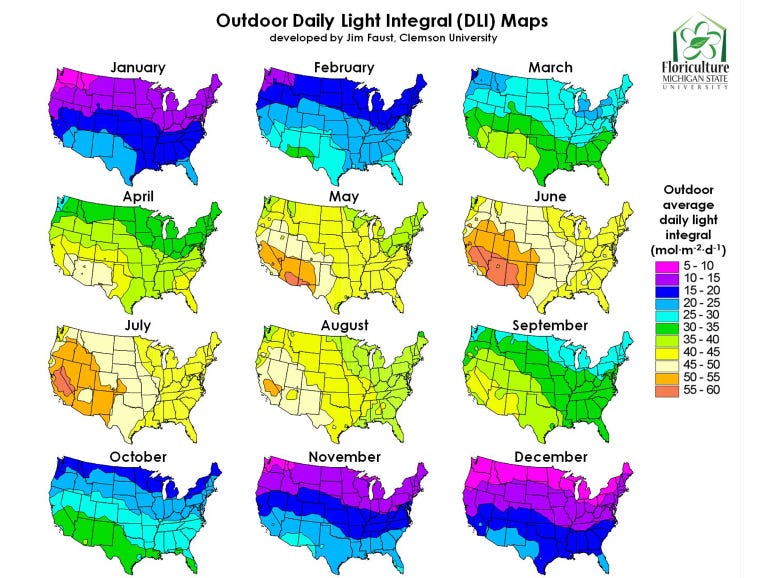

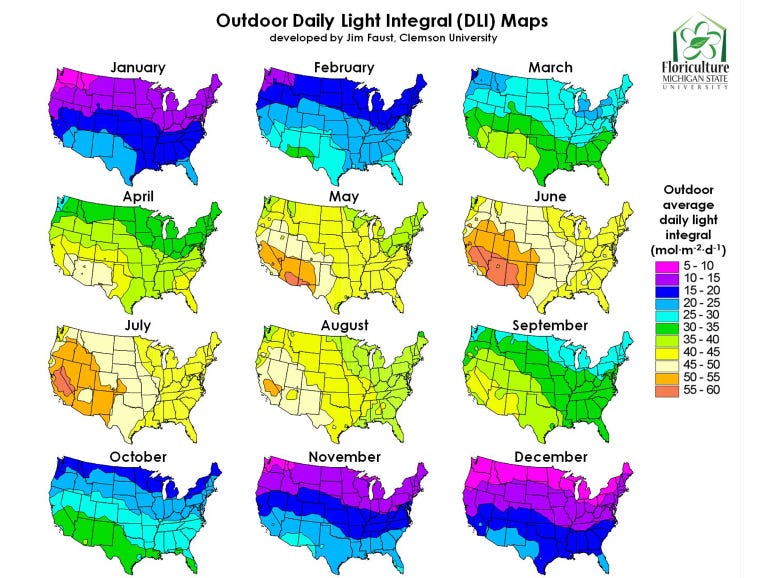

The daily light integral is measured in mols per square meter per day, and that varies depending on the time of year. In summer, you can get as much as 65 mols per square meter per day, while a cloudy day in winter generates between 1 and 3 mols per day. Calculating the daily light integral and making sure your plants get their required amount of light is crucial. It also helps determine what kind of supplemental lighting is needed.

Daily light integral maps show how much mols are generated on average. “So, if you’re propagating things in the middle of winter, it might be viable for you to buy more supplemental light to have more crop turns for propagation,” he said.

MOTHER NATURE’S LIGHTING: A daily light integral map is helpful as it can show you the average amount of natural lighting per month.

MOTHER NATURE’S LIGHTING: A daily light integral map is helpful as it can show you the average amount of natural lighting per month.

Another thing to consider is the amount of light that can make it into the greenhouse, called transmittance. In an average greenhouse, 50% to 70% of light gets through. At his research facility at Cornell, where he has a single-pane greenhouse with lots of overhead structure, Mattson said he gets 50% light transmittance.

“So, if you’re getting 10 mols of light outside and 50% light transmittance, you’re actually getting 5 mols of light inside,” he said. The difference would have to be made up using supplemental lights.

Winter darkness means more lighting

For plugs and cuttings, which often get started in greenhouses in winter, between 8 and 12 mols of light are needed after callous formation to drive good root development and to speed up propagation. For bedding plants, between 10 and 12 mols are needed to build good biomass and get decent plant quality.

“You can see thicker leaves, more and more larger flowers, faster flowering, increased branching, stem diameter, and increased root growth,” he said.

For vegetables, getting more fruit is the objective.

“So, getting that biomass started early is important,” he said, adding that, on average, 1% more light increases yield by 1%.

For lettuce, 12 to 17 mols per day is ideal. But lettuce can also get tip burn if grown too quickly, especially in varieties where older leaves encircle younger leaves. This is caused by a calcium deficiency where the plant is growing faster and producing more calcium than the roots can take up.

Good vertical airflow, he said, can be used to alleviate this problem because it will help mix air.

TOO MUCH LIGHT: Certain varieties of lettuce can get tip burn if grown too quickly, especially varieties where older leaves encircle younger leaves. This is caused by a calcium deficiency where the plant is growing faster and produces more calcium than the roots can take up.

TOO MUCH LIGHT: Certain varieties of lettuce can get tip burn if grown too quickly, especially varieties where older leaves encircle younger leaves. This is caused by a calcium deficiency where the plant is growing faster and produces more calcium than the roots can take up.

“What that does is it moves air on the young growing points and drives calcium uptake,” he said.

“So, for butterhead lettuce, 17 mols of light with good airflow will get you from seed to a harvestable head in 35 days.”

More light — mols — are needed to grow cucumbers, tomatoes and sweet peppers. Cucumbers need at least 30 mols, he said, while tomatoes and sweet peppers do well with 20 mols per day.

But you also must provide a dark period. For peppers, at least four hours of darkness are needed while tomatoes need six hours of darkness.

“If you don’t do that, they will get yellowing leaves, reduced plant size and yields,” he said. “The dark period is a signal to the leaf to transport sugars to the fruit. Without that darkness, sugars can build up in the leaf.”

Calculating costs

LED lights are much more efficient than traditional incandescent or fluorescent lights, but they are also more expensive.

Calculating the system’s cost along with electricity cost per year will give you an estimate on how many years payback there will be. If the money saved in electricity results in a payback of three or four years, Mattson said the system is worth it.

“Because of that, it's really more important to be able to kind of estimate how many light fixtures you will need for your facility,” he said. “And you can do estimates of what their electricals cost is going to be to run per year.

“You want something that will give you a payback of three to four years at most. Energy efficiency rebates can help, but you have to be careful.”

For more information, go to cea.cals.cornell.edu.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like