After coronavirus-related lockdowns were lifted, stimulus checks were cashed and the economy heated back up, some raw-good costs skyrocketed, most notably steel and lumber.

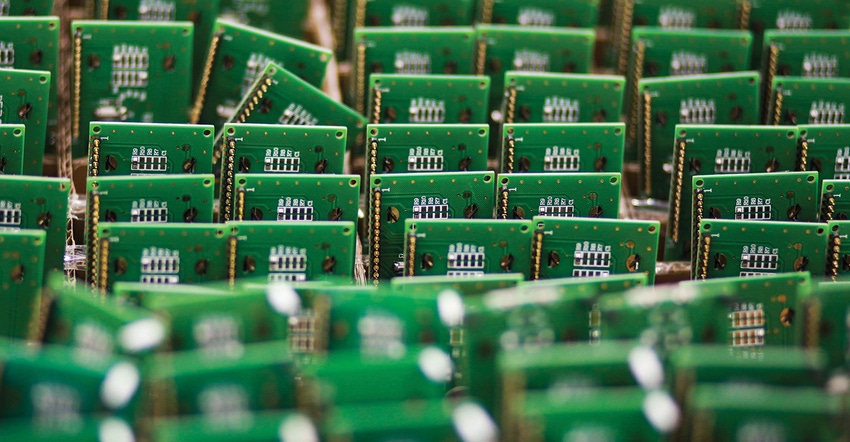

Another demand surge happened in the chip manufacturing industry. Chips aren’t just for computers anymore; they’re inserted into everything from phones and home appliances to pickup trucks and farm equipment. Business is booming — climbing to a record $22.75 billion in the first quarter of this year.

What does this mean for the agriculture industry? Be prepared for a supply pinch in some instances, advises Jason Tatge, CEO of Farmobile.

“It’s basically a perfect storm of high demand and low supply right now,” he notes.

Farmobile, which manufactures a passive uplink connection (PUC) device that collects and organizes a variety of field data, has felt the supply pinch firsthand, according to Tatge.

Normal lead times to acquire parts for the PUC used to average 8-16 weeks — that has since grown to 20-26 weeks in many cases.

“We’re constantly thinking about how to acquire components,” he says.

Related: For the want of a chip, the truck was lost

Not only that, chip supplies have seen an accordion effect — hard to find one day, with an abundance hitting the market soon after. That makes Tatge wary of potential authenticity and counterfeit concerns.

Also, as lead times increase, prices almost always rise in tandem, which is something farmers should be acutely aware of when they’re shopping for new products.

Despite the potential logistical concerns of acquiring certain types of ag tech this year, Tatge hopes farmers will still engage in a deliberate digital strategy moving forward.

“Every field should be a research plot for the farmer, but to do that, you need to take really good notes,” he says. “The problem is that people forget to do one thing or another in the heat of the moment. That’s a huge friction point, and data doesn’t always get entered correctly.”

Tatge also wonders whether the coronavirus pandemic will cause a sea change in supply chain logistics moving forward.

“We’re seeing signs that the ‘just in time’ inventory system of the last two decades creates a lack of visibility,” he says.

Tatge remains confident that these ripples in the industry will soon smooth over, so farmers won’t likely suffer long-term headaches from the current chip shortage.

His focus for now remains on getting past these logistical hiccups and helping more farmers master their field data.

“I continue to preach, ‘Collect the data,’” he says. “It’s a digital asset. Just like cash you put in the bank that you’re not quite sure what you’re going to do with it, there are opportunities to use data going forward that will put you at a big advantage.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like