August 3, 2016

Research and farmer experience proves that leaving soybean residues undisturbed on the soil surface after harvest curbs soil erosion. Now, a study in Iowa suggests eliminating fall tillage could also be a key management practice to reduce the amount of nitrate-nitrogen lost through tile-drained soils into downstream waters.

A study by the Iowa Soybean Association (ISA) and the Iowa Institute of Hydraulic Research at the University of Iowa analyzed water quality data from samples collected by Agriculture’s Clean Water Alliance and compared it to fertilization data of ISA’s On-Farm Network in Iowa’s Raccoon River Watershed over a 15-year period, from 1999 to 2014.

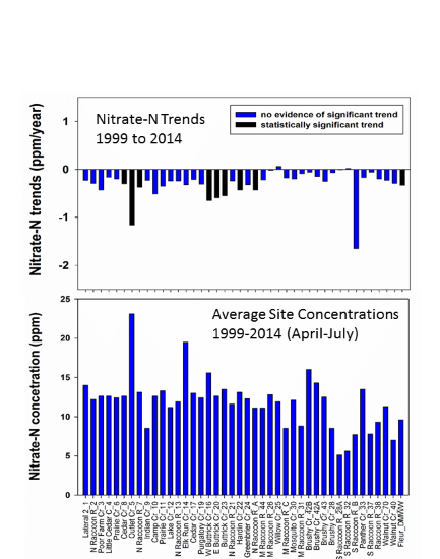

“Conventional wisdom is with increased corn acres and increased nitrogen use, you’d see more nitrate-nitrogen in the rivers downstream,” says Roger Wolf, ISA environmental programs and services director. “But when a team of scientists looked at nitrogen use and corn acres in the Raccoon River Watershed over the past 15 years, they found a 19 percent increase in corn acreage and a 24 percent increase in nitrogen application to corn. Despite those increases, in 39 of the 41 water sampling sites, there were small but statistically significant decreasing trends of nitrates in the water.”

“One might conclude from these data that fertilizer use efficiency improved,” says Dr. Chris Jones, a research engineer at the University of Iowa and part of the study team. “But we believe that was not the case. The amount of nitrogen leaving the watershed in the harvested grain actually declined a little bit during our study.”

“One might conclude from these data that fertilizer use efficiency improved,” says Dr. Chris Jones, a research engineer at the University of Iowa and part of the study team. “But we believe that was not the case. The amount of nitrogen leaving the watershed in the harvested grain actually declined a little bit during our study.”

Tilled soybean residue leaches

That led the research team to consider the effects of the decrease in soybean acres on nitrate levels in water bodies. “Especially in tile-drained soils in Iowa, nitrate leaching potential is greatest when soil nitrate is readily available and no plants are growing for nitrogen uptake,” Wolf says. “The research team found that nitrate resulting from incorporation of soybean residue would be immediately vulnerable to leaching, and would stay that way as long as the ground was unfrozen to the depth of tile drainage.”

Other studies have shown heavier crop residues in a continuous corn situation can return as much as 20 pounds per acre per year of soil organic N to soil N stocks, and increase soil organic matter and total N in the soil, while the soybean phase of a corn-soybean rotation favors mineralization of soil organic N stocks into leachable nitrate-nitrogen.

“From our On-Farm Network data, we know there’s a higher risk that corn after soybeans will be deficient in nitrogen than with corn after corn,” says Dr. Peter Kyveryga, operations manager of analytics at ISA. “Corn has more residue, with a higher carbon to nitrogen ratio. That high ratio may result in no net release of N,” Kyveryga says. “But soybeans have less carbon, and they decompose very quickly.” He also notes water transport has a lot to do with nitrate leaching. “Soybeans are planted later in general and have less uptake of water than corn,” Kyveryga adds. “There’s also more evapotranspiration with corn, resulting in less total water in the soil.”

“Understanding these processes could prove important as we try to reduce the loss of nutrients to Iowa streams as part of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy,” Jones says.

Jones says he and his colleagues believe that declining soybean acres may have reduced the cropped areas most vulnerable to nitrate loss, more than compensating for the increased fertilizer inputs on corn acreage.

Systems approach to water quality

“We know we can’t just focus on fertilization of corn. We need a systems approach to improve water quality. It also demonstrates the power of monitoring water quality. Without this data, we could easily have missed this important and counter-intuitive conclusion.”

Without this kind of data, Wolf says there’s a risk that agriculture, industry and society might chase the wrong solutions. “As we work on watershed plans in the Raccoon River Watershed, we take a science-based approach and consider the practices that address the points illuminated in research,” Wolf says.

Wolf says the data points to no fall tillage and to less tillage overall, along with more use of cover crops. “If we get something growing with cover crops, we have a better chance of keeping water and nutrients in the landscape for crops and avoid loss to water resources. Farmers are going to win with less tillage and cover crops.”

Embrace nutrient reduction

While some farmers resist or are slow to react to Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy, Wolf embraces it. “I believe we can use the Nutrient Reduction Strategy to improve the efficiency of our cropping systems. It can be a catalyst for better agricultural performance. No-till and cover crop, farmers get this—they’re on board. Carbon management, better soil health, less nitrates in the rivers—they all fit together.”

David Ausberger, a no-till farmer who’s incorporating more cover crops into his system near Jefferson, agrees. He’s contributed to and learned from On-Farm Network data on his central Iowa farm within the Raccoon River Watershed. He says he learns the most from his own strip trials; he has multiple trials on his own land each year.

“I learn something new with cover crops each year. I’m no scientist, but I can believe there could be nitrate leaching after soybeans—we put rye out following soybeans and I’ve seen it soak up nitrogen,” Ausberger says. “My thought is we need to take the long view, and replicate Mother Nature with farming systems that mirror what would be happening on the land if we weren’t farming it. That means a system that includes roots growing in the ground in the winter, allowing earthworms and bacteria to do their thing.”

The Power of Data

Unlike studies that have estimated fertilizer inputs, this analysis used actual management data from 698 farms in the Raccoon River Watershed who participate in ISA’s On-Farm Network. Data from multiple years included crop rotations, timing of fertilizer and manure applications, rates and total N applied, tillage systems and other key production information.

The water samples came from Agriculture’s Clean Water Alliance (ACWA) monitoring program that began in 1999. Samples were taken every other Thursday, April through July, the time of year 66 percent of N-loading occurs in Iowa streams.

Water samples were analyzed by Des Moines Water Works and Iowa Soybean Association labs, both certified by the State of Iowa for nitrate analysis.

“Having the On-Farm Network’s unique database and 6,842 water samples from 64 sites in the watershed over a 15-year period allowed us to analyze fertilizer inputs and nitrate-nitrogen in downstream waters,” says Dr. Peter Kyveryga, one of the study’s team members.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like