Face and horn flies are the most common cattle pests, but horn flies are the one which causes the most damage.

Now that we're in the wet part of spring and early summer, it's the time horn fly populations build fastest.

The average meal size by a single horn fly is only 1.5 mg of blood per feeding (Kuramochi and Nishijima 1980), each fly takes between 24 to 38 blood meals per day (Foil and Hogsette 1994). Therefore, the sheer numbers of flies infesting an animal, as well as the numbers of blood meals taken daily by each fly, can result in substantial blood loss (Harris et al. 1974) and nearly constant irritation.

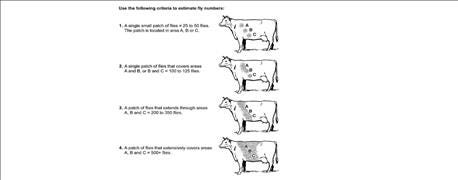

Research in years gone by suggests economic thresholds for various cattle, a point beyond which it should pay off to treat livestock. Calves and dairy cattle generally are considered to be worth treating when levels reach 50 or more flies per animal. Beef cows can tolerate up to 200 flies per animal, while bulls can tolerate the greatest number of horn flies. Very fertile bulls with high testosterone may attract more flies.

Use several methods

By all reliable accounts, an integrated pest management (IPM) approach to control is most effective, and includes management, mechanical, chemical, biological and perhaps genetic controls.

It helps to know the adult horn fly rarely leaves the animal except to lay eggs on the edges of fresh manure pats. The life cycle is 10-20 days, meaning the reproductive cycle, but the horn fly adult can live six to eight weeks.

Adult horn flies feed 20-35 times per day with piercing, sucking mouthparts, and rarely leave their host animal.

A Texas A&M veterinary entomology publication addresses control methods within the framework of the lifecycle. It says there are three general approaches to reduce horn flies:

1) Prevent successful breeding by making manure unavailable or too dry or wet for the larvae to survive or kill the larvae before they become adults

2) Kill adults before they begin to cause economic loss and before their numbers build too high

3) Exclude adult fly entrance to livestock facilities by using screens or other barriers, or remove on pasture them using traps

The first is the most effective point to disrupt horn flies, with the most options available.

Some relatively large, pasture-based operations can move cattle fairly quickly, leaving behind the fly larvae with poor access to host animals for the flies when they emerge. However, some sources say horn flies can fly more than nine miles to find a host.

Dung beetles in high populations can decimate manure piles, burying most of the manure and often the fly larvae with it. They also help scatter and dry the manure, making in unfit for fly larvae development.

It is unclear whether dung beetle larvae can tolerate the feed-through insecticides, also known as insect growth regulators (IGRs). A North Carolina laboratory study suggested minimal effect from light doses of the IGR methoprene on one dung beetle species.

This Australian publication offers some thoughts on fly-control and other insecticides less harmful to dung beetles.

Fly populations can also be reduced by predatory mites, beetles, and other fly larvae that feed on the developing horn fly larvae. Parasitic wasps are said to be ineffective in pasture situations.

Florida entomologists say the IGR feed-through products and boluses kill only the immature stages of the horn fly and do not affect the adult flies feeding on the animals. Therefore, because the adult flies are not killed, and because new adult flies may emigrate onto cattle from nearby untreated herds, feed-throughs are not considered cure-all treatments.

Adult-fly control

Eartags can still be effective, but the continual exposure flies get to the tags can render either organophosphate or pyrethroid tags poorly effective very quickly.

A Texas publication suggests these four guidelines to help use ear tags effectively.

1. Avoid tagging cattle until there are more than 200 horn flies per cow. This delay minimizes the chance for the flies to develop early-season resistance to the insecticide in the tag. If you do not tag cattle until the horn flies appear, the tags will remain effective late in the year when horn fly populations rise.

2. Read the ear tag labels carefully to determine when to remove them from the animals, and do not use the tags beyond their recommended useful life. If left in longer, the flies are exposed to lower insecticide doses, which may increase chances for fly populations to develop resistance.

3. Rotate classes of insecticides (not brand names of tags) every year. Most ear tags contain one of two classes of insecticide— pyrethroid and organophosphate. If you use the same class of insecticide 2 years in a row, horn flies can quickly become resistant.

4. Do not use ear tags that contain both pyrethroids and organophosphates. These combination tags do not slow resistance development and may actually increase it.

Back rubbers, dusters and other means of delivering insecticides can be effective, if cattle are forced to pass through them. The fact horn flies rarely leave their host makes them susceptible to on-animal chemical control measures. Research has shown self-treatment methods are less effective.

To learn which insecticides are legal in your state, try this website of registered pesticides by state for a variety of pests and animal types.

Fly trapping

A walk-through fly trap is a non-chemical method of control that collects and kills horn flies directly from cattle. The animals must be “forced” to pass through the trap regularly as with the chemical options described above.

The same forced use of a fly trap, perhaps between pastures in controlled grazing or on the way to water or a feed source can be very effective. Missouri has a fact sheet and plans available online for a fly trap.

Pick resistant cattle

Last but not least, a few forward-thinking producers try to select cattle that show more resistance to all flies. This is possible and was shown by a researcher in Arkansas to be a viable opportunity, although not a quick fix.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like