July 27, 2020

An article I wrote a month or so ago hit on a lot of pests to watch for in soybeans, focusing on the more common ones. At the time, we were in pretty solid shape in terms of soil moisture, so we didn’t spend much time on pests that can hit when hot summer temps combine with dry weather. With that dynamic changing in much of the state, it’s time to share a “heads up” on some sporadic pests on the rise this season.

We are starting to get reports of spider mites across Iowa, primarily in the drier areas. Maybe by talking about dry weather and spider mites, they’ll both go away for the rest of the summer and you can ask, “What ever happened with the dry weather and spider mites in that article I read?”

The two-spotted spider mite can be a problem in soybean fields, and sometimes in corn, in hot and dry conditions. Mid- to late July through August is typically when they hit economically damaging levels. The literature says “two-spotted spider mites can increase whenever temperatures are greater than 85 degrees F, humidity is less than 90%, and moisture levels are low. These are ideal conditions for the two-spotted spider mite and populations are capable of increasing very rapidly.”

Scouting for spider mites

We typically see them start to become a problem at field edges, and they can disperse with wind to develop a field-wide infestation quickly. Iowa State University recommendations start with checking the edge rows to see if mites can be found. If you find them, estimate populations throughout the field by walking a "Z" or "W" pattern.

Early symptoms of two-spotted spider mite injury are little yellow dots (called stippling) on the lower leaves of plants. The mites typically start their feeding at the bottom of soybean plants and move up the plant after wrecking the lower leaves. Since they pierce bean leaves and draw plant sap out, the damage they do to the soybean leaves exacerbates water loss and plant stress under hot and dry conditions.

If left unmanaged, infested leaves turn yellow, then brown and eventually can die and fall from the plant; it isn’t a pretty sight. Sometimes we can find webbing on the edges and underside of leaves, but I haven’t found that to always be a reliable and timely scouting key. Mites can reduce soybean yield by 40% to 60% when left untreated. Drought-stressed plants could experience even more yield loss. Shatter loss can also increase significantly in fields that had spider mite pressure.

To spray or not to spray?

If you see spider mites in your field, should you spray an insecticide? I wish I could give a solid set of criteria, but spider mite treatment economics depend on a lot of dynamic factors.

ISU Extension entomologists say, “The decision to treat should take into consideration how long the field has been infested, mite density including eggs, mite location on the plant, moisture conditions and plant appearance. A general guideline for soybeans is to treat the crop between R1 to R5 stage of growth (bloom through beginning seed set) when most plants have mites, and if there is heavy stippling and leaf discoloration apparent on lower leaves.”

Things to think about if we have to tackle spider mites this season:

Chemistries limited. We don’t have a lot of variety in chemistry to battle spider mites. Organophosphates are the primary insecticides for two-spotted spider mite control (dimethoate and chlorpyrifos), with only one pyrethroid (bifenthrin) being very effective.

Patience needed. Don’t treat too early or try to do a “preventive” treatment for spider mites. By eliminating natural enemies that can help suppress spider mite populations, these types of applications could cause more problems. Several times over the years I’ve seen fields where an insecticide was thrown in with the last post weed treatment or a fungicide treatment, as a just-in-case treatment, only to see spider mites flare up in those fields. So as a heads up, fields where a just-in-case insecticide was thrown in should be monitored closely for spider mites.

Scout for success. Insecticides may not kill the eggs, so scout fields five to seven days after application to determine if a second application is necessary. If we must make a second application, if at all possible, rotate to the other class of chemistry.

Coverage critical

For the most part, the insecticides need direct contact to kill mites. With the little critters spending most of their time on the underside of soybean leaves, coverage is key to getting the best results. By coverage, I mean a lot of water — like 20 gallons per acre through a ground rig.

Sure, there are cases where 15 gallons per acre has done the job. On the other hand, hauling water to a ground rig and loading a few extra times is a good trade-off for having better control and reducing the odds of a second application.

For aerial application, it gets more complicated. Experts recommend 5 gallons per acre through a helicopter or airplane, and that would be ideal. Getting pilots to fly 5 gallons per acre isn’t an easy sell and can mean higher application fees.

I’ve seen good results at lower aerial GPA, but I’ve also seen fields with lower GPA need a second treatment a few times where others in the area at higher GPAs didn’t. How many gallons to run via air often comes down to what your chemical supplier, the pilot and you can all agree on and see as the best risk-and-reward scenario — and there isn’t always much flexibility.

I used to think maybe we could scout field margins and spray them earlier to try to avoid spraying the entire field. It only worked a few times — in years where we didn’t end up spraying a lot of fields for spider mites since pressure was low and treating was questionable anyway. If you have a significant spider mite outbreak, and they are in your field borders, I’d recommend treating the entire field.

Watch and follow the preharvest intervals spelled out on insecticide labels. These label restrictions specify the number of days after spraying that you must wait before you can legally harvest the beans.

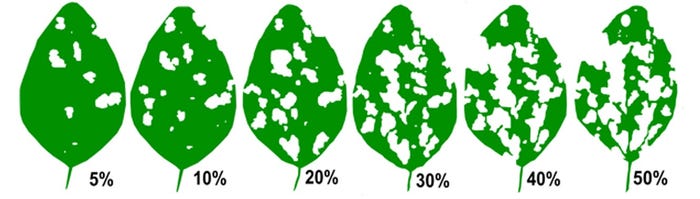

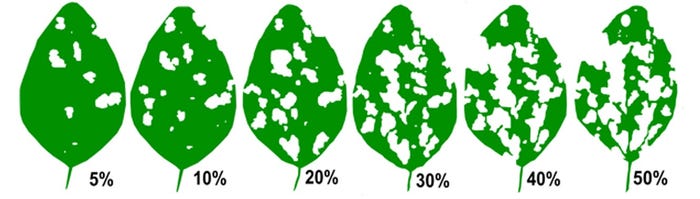

DEFOLIATON: This illustration shows what various percentages of soybean leaf defoliation by insect pests look like.

What’s eating my leaves?

This year has been interesting to say the least, so why would soybean pests be any different? In Iowa, there is a longer list of pests munching on beans than most years, so scouting deep into the growing season will be needed.

Japanese beetles have been problematic in areas this summer. With an adult lifespan of four to six weeks, farmers should keep an eye on the beetles’ defoliation damage through July and into August depending on growing degree units in an area.

Thistle caterpillars and green cloverworms have been noted in areas in Iowa this summer. While they are noted in the literature to “rarely cause economic injury in Iowa,” it’s worth keeping an eye out for them.

Japanese beetle, thistle caterpillar and green cloverworm are defoliators. When a bunch of holes are found in soybean leaves, it’s bound to make anyone nervous. The good news is beans can withstand a lot of defoliation, even after they start flowering, when the most common economic threshold is 20%.

What does 20% defoliation look like? The phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” sums up soybean defoliation since describing the various percentages is difficult. Smartphones with good cameras can help, and scouting apps are handy. But knowing what 20% looks like on a soybean leaf is only part of the “picture.”

It seems like every piece of entomology literature ever written contains the phrase “soybean defoliation is often overestimated.” As cliché as that line seems, it has stuck around because it is spot-on for several reasons.

Different pests often feed at different levels of the canopy, so evaluate the entire picture. Fields with 30% or 40% defoliation in the upper canopy look awful. It can be tempting to pull the trigger after seeing that, but if the rest of the canopy is in good shape, the overall percentage may not approach 20%. Field borders and edges usually look tougher than the rest of the field, so wading farther in and scouting the whole field is necessary.

Iowa State University is also getting early reports of soybean aphids and grasshoppers, so field scouting will be critical for the rest of the growing season. The bright side is when scouting beans, it’s easy to maintain social distance and you probably won’t have to wear a mask.

Most pest management information including thresholds and treatment advice can be found at ISU Integrated Crop Management News.

McGrath is the on-farm research and Extension coordinator for the Iowa Soybean Research Center at ISU. Contact him at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like