September 27, 2010

There are major soybean disease problems lingering, including frogeye leaf spot, sudden death syndrome, charcoal rot, soybean mosaic and bean pod mottle viruses, but most are well-studied with potential control measures established across states and regions.

New problems occur when a disease emerges and there is no prior knowledge of the pathogen, its biology and effect on yield. Such is the case with soybean vein necrosis, a disease of unknown etiology, observed for many years across the Mid-South and Midwest.

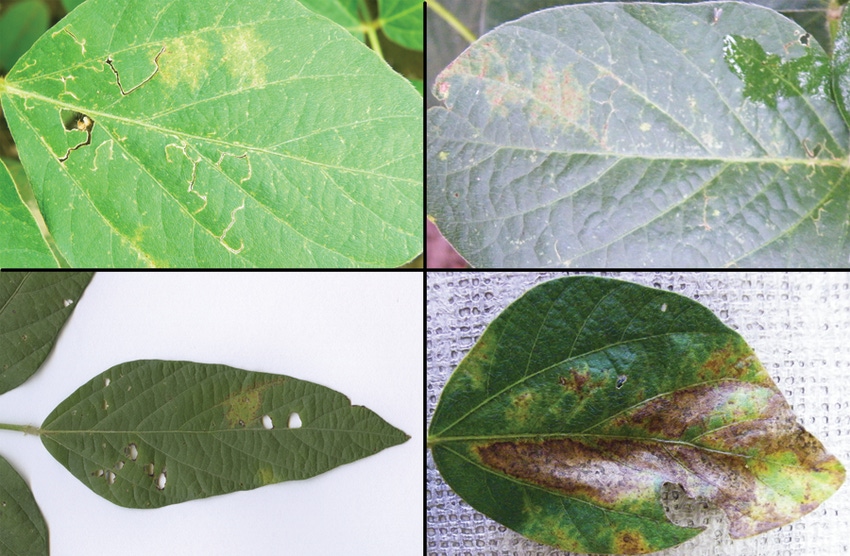

The first symptoms are observed in June for Arkansas and Illinois and appear as light green patches, normally in proximity to the main veins of a leaf. As the season progresses, lesion areas die, resulting in a scorched appearance to severely affected plants.

Symptom severity appears to be cultivar-dependent, with some showing severe symptoms, whereas others show the death of infected leaves but only in limited areas on an infected leaf.

In 2008, Dr. Melvin Newman (University of Tennessee) and Dr. John Rupe (University of Arkansas) provided our laboratory with samples from Tennessee that had typical virus symptoms but tested negative for 16 previously documented soybean viruses.

We discovered a new virus in the infected material and provided our findings to Dr. Reza Hajimorad (University of Tennessee), who confirmed that samples with similar symptoms he collected were also infected with the new virus, establishing a strong association between virus and symptoms.

For this reason we named the new virus soybean vein necrosis virus (SVNV). We are now working closely with Hajimorad’s group to develop detection tests and better understand the virus and its biology.

What we know so far: SVNV belongs to a group of thrips-transmitted viruses. Viruses in this group can also infect the insect. Once this happens, viruses can be transmitted for the lifespan of the insect.

Over the past two years numerous samples have been submitted and screened for the presence of the virus. In addition to screening for the virus, we have developed a test to look at the diversity of the virus across a broad geographic area. We are attempting to fingerprint the virus, with the hope that we will be able to identify its specific origin.

With the data we have so far, using isolates collected from several different states, it appears that SVNV is probably a new introduction to soybean.

What we are trying to accomplish: Vector identification. Although it is almost certain that thrips are vectors of the virus, we do not know which of the thousands of species out there can do so.

Why is this important? Thrips are ubiquitous pests and trying to eliminate them can be very costly to the grower. If we identify an efficient vector then we can (a) learn of the critical time that it is present in the field and try a limited control program to eliminate the vector and (b) see what other hosts the vector feeds on and thus be able to identify alternative hosts the virus may overwinter on.

Host range of virus

Currently, experiments are being conducted to determine the host range of the virus. This crucial step, while time consuming, is extremely important to combat SVNV because the virus can hide in other plant species (even without showing any symptoms) that will serve as a constant inoculum source, undermining the efforts to eliminate the virus from the system.

Several viruses have been documented to be seed-transmitted in soybean. Even though viruses in the group that contains SVNV are not known to be seed-transmitted, we will be testing SVNV for this property as even that minimal possibility can be important in the overall movement of the virus between different areas.

Viruses can result in yield losses in single-infections, but there is a large amount of data reporting that viruses can affect yield in a major way when two or more accumulate in a plant. Our goal is to evaluate the effect of SVNV on yield when found in plants alone and with other soybean viruses such as soybean mosaic or bean pod mottle.

While we are accumulating data on the virus, we have started testing for resistance in cultivars and advanced selections. Several accessions from the program of Dr. Stella Kantartzi (Southern Illinois University) are being tested and similar work will soon begin in Arkansas in collaboration with Dr. Pengyin Chen.

We are early in our experiments and presently do not know enough about the virus and the disease to make recommendations, but we want growers to be aware of the disease.

As this work moves forward we will determine the yield effect of the virus in single and mixed infections with other viruses and will eventually be able to make recommendations on the necessity of pesticide usage to eliminate the vector(s).

This will be region-dependent, but we have a strong network assembled which includes (in addition to the previously mentioned individuals) Dr. Tom Allen and Dr. Sead Sabanadzovic (Mississippi State University) and Dave Johnson (Missouri Department of Agriculture).

Through this team, information will be disseminated to growers to minimize input and maximize profit. We also expect to find germplasm that shows tolerance or even immunity to the virus that will eventually make its way into commercial cultivars.

e-mail: Yannis Tzanetakis

You May Also Like