Think differentIn addition to increasing corn yields and cutting nitrogen expense, keeping soybeans in the rotation lowers next year’s corn rootworm management costs, says Ken Ostlie, University of Minnesota Extension entomologist. “Rotation resets the population of corn rootworms in a field, so you can get by with fewer rootworm inputs the next year. You can eliminate insecticide use, or plant all non-Bt corn that first year.”

September 25, 2013

The Schrader family’s best corn field has a high-tech problem. Fortunately, there’s a low-tech solution: crop rotation.

Corn rootworms in this longtime continuous-corn field seem to have become immune to the Cry3Bb1 trait, the most common source of transgenic rootworm protection, says Keith Schrader, who farms with his sons near Nerstrand, Minn. In 2011, YieldGard VT Triple knocked out just 25% of corn rootworms in this field, compared to an expected kill rate of more than 95% in fields where the trait works, says Ken Ostlie, University of Minnesota Extension entomologist.

Due to a rental agreement, this field remains in continuous corn, but to achieve long-term rootworm control, “We’re going to have to rotate to soybeans,” Schrader says. Ostlie agrees: “Rotation would totally solve this problem.”

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to CSD Extra and get the latest news right to your inbox!

Pest management is the main reason the Schraders keep soybeans in the lineup on their 3,700-acre operation. Even though crop prices and relative yields often favor corn-after-corn, soybeans offer valuable benefits, Schrader says. Along with better pest management, beans in the rotation let growers:

•diversify weed-control chemistry and cut resistance risk

•reduce tillage

•save on N, fuel and labor

•spread out fieldwork

•increase corn yields

A soybean-corn rotation “is a good risk-management strategy for both crops,” says Shawn Conley, University of Wisconsin Extension soybean agronomist. Corn yields are 13% to 19% higher after soybeans, according to 30 years of University of Wisconsin trials. Input costs are lower, and in weather stress years, soybeans and rotated corn are more resilient than continuous corn.

Joel Schreurs follows a two-year, corn-soybean rotation on about 80% of his 1,000-acre operation near Tyler, Minn. “It breaks the cycle of diseases, insects and weeds, and gives you more avenues of crop protection. That’s the biggest value for me.”

Rotation is still the best way to control corn rootworms in most of the Corn Belt, says Tristan Mueller, operations manager for the Iowa Soybean Association’s On-Farm Network. “One year of soybeans will knock out CRW populations.” After that, Ostlie adds, you may only need to plant soybeans every few years to keep them in check.

Rotate crops and tillage

Another advantage of keeping soybeans in the rotation is less need for tillage, Schrader says. On his erodible ground, he no-tills beans into standing cornstalks every third year. That’s followed by minimum tillage for first-year corn to incorporate nutrients. Even in the northern Corn Belt, Conley says, “no-till soybeans yield the same as tilled.” Likewise, there’s no yield benefit for tillage on first year corn after soybeans, adds Joe Lauer, University of Wisconsin corn agronomist.

To make the most of a corn-soybean rotation, though, “You need to treat soybeans as a first class citizen, rather than as a ‘rotation’ crop,” Conley says.

That can be a challenge for time-strapped farmers, Mueller points out. “Soybeans may get less attention because they respond less than corn to intensive management.” Still, Schreurs says: “Don’t treat soybeans as an off-year crop. Give it the same care you do your corn crop.” You should:

Select the best genetics. “Spend the time to select superior soybean genetics,” just as you do for corn, Conley says.

Plant narrow rows. Schreurs switched to 10-inch soybean rows for soybeans after University of Minnesota research showed a significant yield advantage. Research from around the country has affirmed that. For example, the multi-state, high-input USB-sponsored soybean trials, known as the “Kitchen Sink” study, found that narrow rows boosted yields by 3% to 5%, compared to 30-inch rows, Conley says.

Fertilize. Growers often neglect soybean fertility, Conley says, expecting soybeans “to scavenge whatever nutrients are left from the corn crop.” Schreurs does grid soil sampling yearly and applies phosphorus and potassium separately for both corn and soybeans. “Higher commodity prices allow us to run an additional pass with the fertilizer spreader.” What about foliar fertilizers? “You get more bang for your buck with soil-applied than foliar feeding phosphorus and potassium,” Conley says.

Apply preemergence herbicides. In the era of herbicide-resistant weeds, a total postemergence weed-control program is no longer prudent, Conley says. “There is a lot of data to show the economic value of preemergence herbicides” for soybeans, Conley says, “even if you don’t have resistant weeds.”

Invest in seed treatments. In Wisconsin trials from 2008 to 2011, seed treatments increased average yields from 0.6 - 2.3 bushels per acre. However, the probability of a profitable response depends on seed-treatment cost and crop value, Conley says. “Our experience has been that when spring conditions are cool and wet, and when planting date is in late April to early May, seed-treatment fungicides are an effective tool, especially given the current value of seed.”

Control volunteer corn early. Volunteer corn is very competitive with soybeans and also weakens the rotation’s value for managing corn rootworm, Ostlie says. These plants are “like a bridge from one corn crop to the next.”

Conditions that favor soybeans

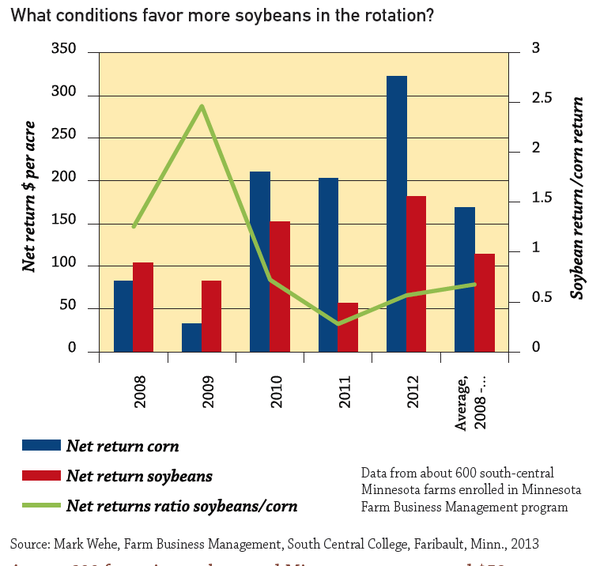

Among 600 farms in south-central Minnesota, corn earned $59 to $147 per acre more than soybeans from 2010 to 2012, says Mark Wehe, Minnesota Farm Business Management educator in Faribault. Corn-on-corn acreage jumped, especially on highly productive fields, where the advantage for corn was even greater.

A soybean-to-corn price ratio of 2.3 or greater favors more soybeans in the rotation; that appears to be the trend in 2013 and 2014. University of Illinois 2014 crop budgets suggest a profit advantage for a corn-soybean rotation over both corn-corn-soybean and continuous corn. An average corn-to-soybean yield ratio of 3.3 or greater favors more corn in the rotation, while a lower yield ratio favors a traditional corn-soybean rotation.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like