Temperatures are still cold in Nebraska, but planting time is only a few months away. And as spring approaches, one of the many decisions growers will make is whether to inoculate their soybeans with nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

But first, there are a few things to understand about soybeans, their relationship with rhizobium, and biological nitrogen fixation, says Nathan Mueller, Nebraska Extension cropping systems educator.

"People don't always realize there are two different species of Bradyrhizobium that can form symbiosis with soybeans," Mueller says.

There's Bradyrhizobium japonicum, which usually is the first species to come to mind when it comes to nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and there's Bradyrhizobium elkanii. Fields can have either, or both.

That relationship with rhizobium starts at the root hair level.

"Bacteria attach to soybean roots in response to an attractant given off by the roots, and that compound is usually a flavonoid," Mueller says. "Soybeans start the process with an attractant, and the bacteria respond with a signaling module called a nod factor. That causes the soybean root hair to deform, curl and eventually become a nodule. That initial process, the change in the root hair, is where abiotic stresses are, like high or low pH, or salinity."

And Bradyrhizobium japonicum is long-lived.

"Bradyrhizobium japonicum can survive in soils for over 20 years without soybeans growing in the field," Mueller says. "Once you've inoculated a field and grown soybeans there, you could walk away and then plant it again in 20 years, and it may not be the level you want, but they're fairly long-lived.

"Bacteria aren't that mobile in the soil. Based on one study, from where they've put inoculum or bacteria, 20 years later, they only moved 150 feet. Unless there's soil erosion, the chance of moving that bacteria is pretty slim in the soil."

Through this partnership, soybeans get nitrogen, and bacteria get carbohydrates in return.

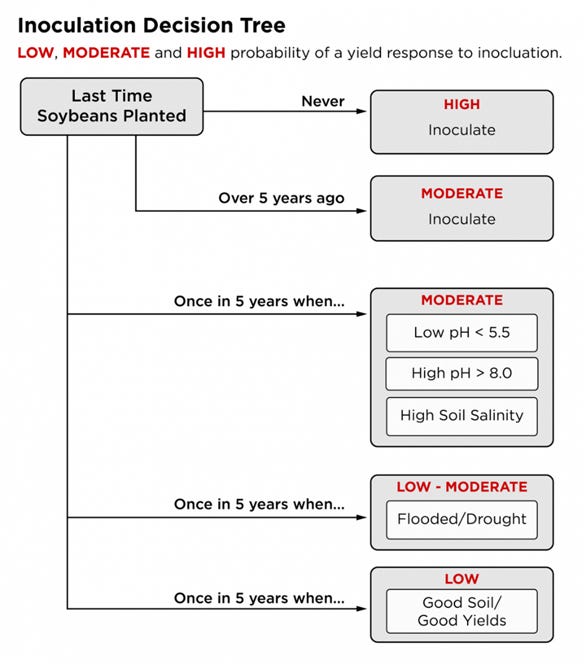

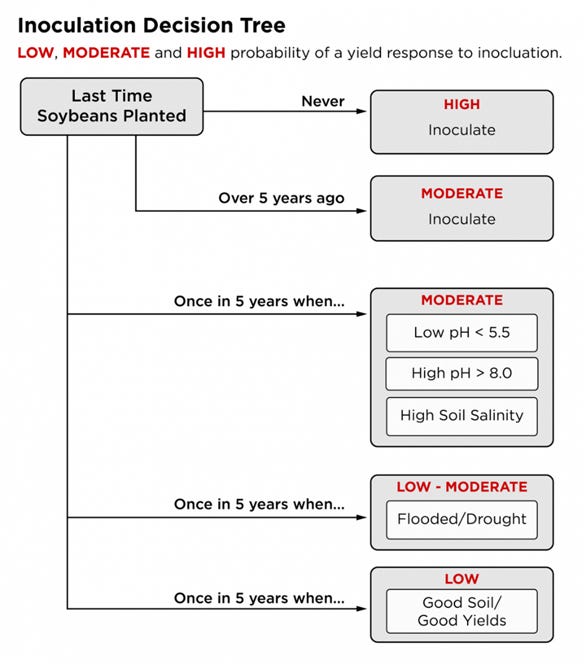

YIELD RESPONSE: This decision tree — created by Nathan Mueller, Nebraska Extension cropping systems educator, and other Nebraska Extension educators and specialists — outlines the probability for a response using an inoculant based on the field's history and current conditions.

However, there's a range in the ratio of how much nitrogen a soybean plant takes up from the soil versus biological nitrogen fixation.

"Ideally, in a good situation, a 70-bushel-per-acre soybean crop needs 330 pounds of nitrogen. It's a lot more than a corn crop," Mueller says. "About 75%, or three quarters, is coming from fixation, and the other 25% is from the soil. However, the opposite end of the range is about 50-50 from each. The key takeaway is, if you need a lot of nitrogen, you can only expect so much from our soil."

With this in mind, Mueller and other Nebraska Extension educators and specialists developed a decision tree, based on on-farm research studies in Nebraska and other Midwestern states, to help producers determine whether there's a high, moderate, low-moderate or low probability of a yield response to inoculation on a given field.

"Farmers don't have a quick test they can use to see, how many Bradyrhizobium japonicum cells do I have in the soil?" Mueller says. "The decision tree asks questions like, when were soybeans planted last? Do you have high or low pH? Was the field flooded recently? It's going over those situations based on experience to determine the probability of a response."

"Where you haven't had any extremes in soil conditions, you've had good yields, good nodulation, and you've had soybeans in the rotation frequently, there's a low probability of response," Mueller adds. "The bulk of the on-farm research studies have been done in those situations. Only 1 out of 18 on-farm studies in Nebraska showed a yield response."

That is, the probability of a yield response in fields with a recent history of soybeans is extremely low unless the field recently was affected by environmental factors such as flooding or erosion. A regional study involving 73 experiments testing 51 inoculation products across the Midwest over eight years — from 2000 to 2008 — showed an average yield response of zero bushels per acre.

"It might cost $1 to $4 per acre, but when the average yield response is next to zero, the data would suggest if you haven't had problems in the past and have good nodulation, you're not going to make that $4 back either," Mueller says.

Of course, some situations have a higher probability of response. These moderate- and high-probability situations typically come after five or more years of continuous corn, after alfalfa, or in land coming out of the Conservation Reserve Program.

High or low pH, as well as high soil salinity, also can decrease survival. In these moderate-probability situations, yield increases of about 2 bushels per acre have been observed in studies in Iowa and Wisconsin.

The highest probability of response comes in places where soybeans have never been grown — in some cases, yield increases of up to 49 bushels per acre have been measured in Nebraska, although more modest increases of 1 to 10 bushels are expected.

"Look at moderate probability fields with high or low pH, or flood-damaged soils," Mueller says. "That's a situation this year where the probability might be higher, or you might have been in continuous corn for a few years, or you've had an alfalfa stand for four or five years."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like