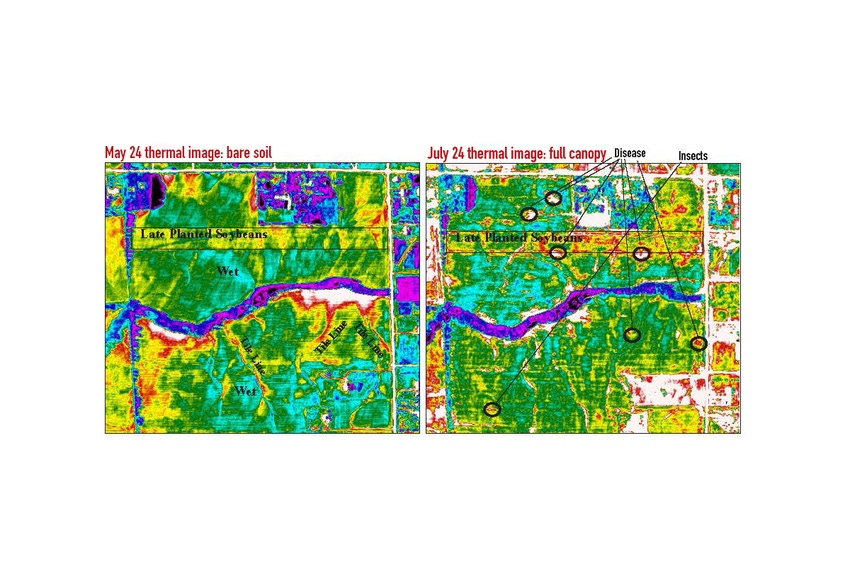

Think differentFlying farmer Brian Sutton’s patent-pending aerial images detect slight temperature variations in fields that lead scouts to problem areas, such as disease, insect problems, wet and cold soils, compaction, planter issues, nitrogen deficiency and other issues. He says thermal imaging is far more precise and sophisticated than the normalized difference vegetation index and infrared technology. Taking photos every two weeks, he sees value with early detection and timely corrective action, as well as analysis after harvest that compares yield variations with thermal variations throughout the season.

June 9, 2015

What is the earliest possible way to detect stress or disease in your corn and soybean fields? Brian Sutton, a flying farmer from Lowell, Ind., takes their temperatures. The thermal cameras used in his AirScout service detects stress and disease in plants before they change color, when he still has time to take corrective action, he says.

“Plants react to disease like humans and animals – they develop a fever,” Sutton says. “A sick plant shuts down the evapotranspiration system from the bottom up. A temperature change of just 1° F is readily apparent in a thermal image.”

The thermal cameras, far more precise and sophisticated than current technology, record only emitted energy, ignoring on-ground color differences. They can even pick up disease in the bottom one or two leaves.

Color variation marks the spot

Temperature differences are recorded with white as the hottest and violet as the coolest, with red, yellow, green and blue in between. However, the relative differences are key, Sutton says. “You might see a difference of 6° F from a well plant to a very sick plant,” he notes. “We’re learning we can pick up any disease with these images, from northern leaf blight to anthracnose.”

Maykol Hernandez, an agronomist for B and M Crop Consulting in Coldwater, Michigan, just started using images produced by the AirScout service. “We don’t have to walk the whole field to see where the problems are,” he says.

Using the thermal imagery service for his customers, Hernandez spotted downed corn in July and identified parts of center-pivot irrigated fields that were lacking moisture. “It’s a valuable part of our service to be able to pinpoint an area of a field that needs water and get it to the crop before it becomes stressed,” Hernandez says. “Even a quarter-inch of water at the right time makes a difference in reducing crop stress.”

Hernandez has had growing interest in the technology from his corn, soybean and tomato grower clients, noting that it is particularly helpful in obtaining information that can be used the following year.

That’s how Tom Wietbrock sees it, too. The Lowell, Ind., farmer does his own scouting. “This was my first year for thermal images,” he says. “I could see tile lines from pictures taken before planting, and I saw differences in one soybean field in these photos that I couldn’t see walking out into the field.”

Impact from previous crop

When Wietbrock observed a distinct color separation between a 58-acre area and a 95-acre area of a knee-high soybean field, he called the seed dealer. “Their reps came out and decided the difference had to be that the corn varieties on those two areas the year before were different,” he says. “The soybeans didn’t handle the corn residues left from the corn variety on the 95 acres as well. There was a 2- to 3-bushel difference in soybean yields. So I won’t use that corn hybrid next year.”

Wietbrock especially wanted the images for 100 acres he purchased and farmed for the first time this year. “We’re mostly no-till, but that farm wasn’t,” he says. “The early photos showed the compaction lines.”

In another field, seedling blight showed up on one of two varieties on about 50 acres, so Wietlock says he won’t be planting that variety next year either. “Just knowing we had that problem was worth this aerial photo service,” he says.

Wietbrock agrees that the photos direct him to problem areas in the field. “You see the color changes, walk to the exact spot and ask yourself, ‘why is it this way?’” he says. “That’s the real value.”

Sutton also believes there’s much to be learned from the set of 10 field images taken over time. “We pull up a yield map, then back up in time looking at these images,” Sutton says. “We might not be able to fix every problem, but at least we will know what it is and how it affected yields.”

Compliment to crop scouting

“I believe a good agronomist or crop scout can bring tremendous value to a farmer, but you have to get him or her to the right place,” Sutton says. “By looking at slight variations in temperatures, you can direct the scouting to precisely the right place during the growing season.”

They fly about every two weeks. “That’s better than sending a scout out to your field three or four times a year,” he says. “Your odds aren’t real high in finding that poor spot when you walk a field without any guidance.”

That said, Sutton stresses that thermal imaging is a tool for crop scouting, not a replacement. “You still have to get on the ground to discover what’s causing the temperature difference,” he says. For example, he uses a rig to spot spray for insects before the problem gets too big.

“Another example is the red area we saw in photos we took for a client,” Sutton says. “When he walked to the area, he discovered it was a nitrogen deficiency. He added N to the affected area, and in the next photo, the problem was fixed.”

Sold on the service

After he took the first set of thermal photos four years ago, Sutton was so sold on the technology he invested in the Indiana-based business AirScout. “That summer, to my eye, the soybeans all looked green – they looked great, in fact, all over the field,” he says. “But from the thermal photo, we knew there were differences in a field close to the house. Soybeans react thermally even more than corn. Ideally, the field would be all blue, but the yellow and green colors in a wide horizontal strip all across the center of a field told us the soybeans had a higher temperature than the rest of the field.

“At first, we thought it might be from a different variety of beans or a different planting date,” Sutton adds. However, they then remembered using a temporary fence to pasture cows on corn stalks the previous fall.

“The photo picked up the compaction caused by those cows and defined the area right up to the fence line,” Sutton says. “We noticed that the warmer yellow colors were on the west half of the pastured area, where the cows entered the pasture. We also saw red in a diagonal waterway area that was wetter, which became more compacted.”

Sutton watched the combine monitor closely to match color variations with yield differences. “We found out what we thought was cheap feed for our cows that wet fall cost us 7 bushels an acre in lower soybean yields the next year,” he says, “and we saw it was still costing us in reduced wheat yields last year, three years later.”

The images also informed Sutton that his combine wasn’t spreading residues evenly across the row and that auger cart travel was causing compaction. “You don’t tend to think about your actions having such a lasting effect on future crops, but this thermal imaging proves it,” he says. “There’s value to looking back at these images from the current crop year, but also in looking back to previous crops. It keeps you from making the same mistakes year after year.”

Sutton has expanded AirScout’s offerings throughout the Midwest, with Texas being added soon. An added yield estimator feature even takes a thermal image in late July or early August and applies a three-range temperature color palate, which a farmer uses to conduct a yield check. The estimator then correlates this data with thermal temperatures over the entire field.

Scientists: Thermal imaging part of multiple flights, multiple sensors

A thermal image is a snapshot in time, says Bruno Basso, an ecosystem scientist at Michigan State University. “The thermal camera gives you the temperature of the plant. If it’s hot, it’s water stressed,” he says. “Then you have to go figure out the cause.”

Basso is a fan of using multiple sensors with multiple flights over the growing season to scout for stress. In his research, he uses a drone equipped with a high-resolution radiometer, a thermal camera and a laser scanner.

Rick Perk, a geoscientist at the University of Nebraska Lincoln (UNL), has used a thermal camera to pick up subtle differences in crops for more than 5 years. “We’ve seen thermal differences in plants with moisture stress – for instance, irrigation anomalies that show a stripe in a field from a plugged irrigation nozzle,” he says.

Perk has been involved with remote sensing for 40 years, conducting close-range crop sensing since 1990 at UNL’s Center for Advanced Land Management Information Technologies.

“Instruments on our aircraft have collected image data from the visible and near-infrared portions of the spectra. The SC640 camera we’ve used expanded those capabilities into the thermal range. Each has its place; I won’t say one is better than another. But timing is critical for farmers,” he adds. “You can’t argue the value of early detection. The big thing is being able to affect the bottom line for the producer.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like