Many non-native pests, from fire ants to slithery, slimy worm-like creatures, have come into the U.S. and made themselves at home, often causing widespread economic damage and other disruptions to life and commerce, says Blake Layton, Mississippi State University entomology professor. “It’s important that we remain on the alert for these invaders," he says. "You never know when one will have the potential to be the next boll weevil — or even worse.”

In 1978, the horror movie, “The Swarm,” hit the nation’s theaters, featuring vast hordes of killer bees that wreaked havoc in south Texas.

Chockablock with big name stars — Henry Fonda, Olivia de Havilland, Michael Caine, Richard Widmark, Fred MacMurray, Richard Chamberlain, Ben Johnson, Lee Grant, Patty Duke, Slim Pickens — the $21 million production (a lot of money in that era) was a colossal boxoffice bomb, lasting only a couple of weeks in theaters.

Although it was subsequently labeled one of the worst disaster movies ever, four decades later it enjoys something of cult status among horror movie buffs.

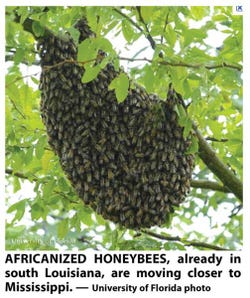

“It was a cheesy movie,” says Blake Layton, Mississippi State University Extension entomology professor, “but it was also somewhat prophetic in that we’ve seen Africanized honeybees, which were dubbed ‘killer bees,’ move into the southern U.S. and become established.”

While not nearly so dramatic on a human scale as in the old movie, many non-native pests, from fire ants to slithery, slimy worm-like creatures, have come into the U.S. and made themselves at home, often causing widespread economic damage and other disruptions to life and commerce, he said at a recent meeting of the Starkville, Miss., Ag Club.

“So, in reality, we can say ‘the swarm’ is still coming.”

Africanized honeybees, which are a sub-species of the common European honeybees, came into Texas in 1990 and have spread from there, Layton says.

“Their movement has been more westward than east, although they’re in south Louisiana, only two parishes away from Mississippi. They are much more aggressive than our native honeybees — the analogy I use is that it’s like comparing a Labrador and a pitbull. When they do move into Mississippi, it will change the way we deal with honeybees.

“Even our ‘native’ honeybees aren’t native; they were brought here by settlers from Europe. The Indians called them ‘white man’s flies.’”

There are more than 1,700 significant insect pest species in the U.S., Layton says, and half or more have been introduced in one way or another.

“The boll weevil is a prime example of how a non-native pest can move in and wreak economic havoc,” he says. “It cost Mississippi farmers millions of dollars before it was finally eradicated. We’ve not had a boll weevil in the state in more than two years.”

Imported fire ants have spread across most of the lower Southeast and across south Texas and into parts of Oklahoma.

“Thus far, we’ve not been able to stop them,” Layton says, “and there’s nothing on the horizon that promises to halt their spread.”

Another species, Argentine ants, “have been here for a long time, but haven’t spread as fast as fire ants. South of Jackson, Miss., they’re quite abundant. They don’t sting or build visible mounds, and they’ll run off fire ants. The difference is that they will come inside houses and other buildings.”

Hairy crazy ants

Recently, the media have given a lot of attention to hairy crazy ants, also called raspberry crazy ants and Caribbean crazy ants.

“These began showing up in Mississippi about three years ago,” Layton says. “They also don’t sting or build visible mounds, but their populations can be really huge, and they will come inside in vast numbers. They don’t bother human food or pet food, but they can short out electrical circuits, well pumps, and other electrical devices, and if you disturb them they can be all over you in 30 seconds. They feed on other insects and plant nectar/exudates.

“Homeowners tell me they can kill them, but they may end up with a half inch thick pile of dead ants.

“We think they originated in South America, were then introduced into the Caribbean, and from there probably came into the U.S. on ships or in potted plants.

“At present, we know of two places in south Mississippi where they’re located, but we think they will spread rapidly. We don’t have any idea how far north they will move.”

Other non-native pests that have taken up residence in Mississippi or elsewhere in the U.S., Layton says, include:

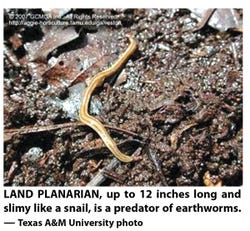

• Land planarian: “It’s long like an earthworm, slimy like a snail, with a head like a cobra.” A predator of earthworms, it can be up to 12 inches in length. It has been in Mississippi for quite a while.

• Formosan termites: “They were first found in 1984 in coastal areas of Mississippi and now about 25 counties have infestations, including one documented at Tupelo in northeast Mississippi this year. They can eat a lot more, a lot faster, than the more common eastern subterranean termites.”

• Brown marmorated stinkbugs: “These have come from the northeast U.S., where they’ve been well-established for some time. They’re harder to control and have a much stronger odor than our other stinkbugs; they’re also more damaging to fruits and some landscape plants. They will also come inside in large numbers; homeowners in the northeast tell of sweeping out five-gallon buckets full.”

• European hornets: “They can be up to 2 inches long and prey on honeybees. We don’t have that many in Mississippi yet, but there are a lot in Arkansas and Tennessee.”

• Giant resin bees: “Something of a curiosity, they showed up in Mississippi about 8 years ago and have spread all over the state. While they don’t bore holes in wood like carpenter bees, they will go into holes already present.”

'Kudzu bug' damages soybeans

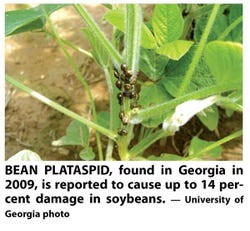

• Bean plataspid: “This pest, also called kudzu bug, was found in Georgia in 2009, and is reported to cause losses of as much as 14 percent in soybeans, and could potentially be a problem across the South. It will also come into homes in the fall.”

• Bean plataspid: “This pest, also called kudzu bug, was found in Georgia in 2009, and is reported to cause losses of as much as 14 percent in soybeans, and could potentially be a problem across the South. It will also come into homes in the fall.”

• Chili thrips: “This one is in Florida, Alabama, and Louisiana, and is likely in Mississippi, although we don’t know if has become established. It can be very damaging to roses, vegetables, fruits, and row crops. It has the potential to become a big deal if it gets established in the state.”

• European wood wasp: “It has been attacking pines and softwood conifers in the northeast. It will attack slash and loblolly pines, which are widely planted in Mississippi. It can devastate entire plantations, and if it becomes established here growers will have to do a good job of thinning trees to promote more vigorous growth to allow the trees to resist the pest.”

• Walnut twig beetle: “Already in Tennessee, it kills black walnut trees. We think it came in from Colorado, where it existed in other walnut species.”

• Granulate ambrosia beetle: “We already have this pest, which bores into the trunk of saplings less than three years old and pushes out frass. Just 10 of them can kill a small tree. We’ve had a lot of calls about from peach growers about this pest.”

• Red bay ambrosia beetle: “It has already killed most of the red bay trees in Georgia and South Carolina. It also attacks sassafras and Florida growers are concerned that it could be a problem in avocados.”

• Crape myrtle aphids, azalea lace bugs, and camellia tea scale: “These are pests of ornamentals widely planted in Mississippi, and can cause varying damage. A common means of introduction is via nursery plants.”

• Mediterranean fruit fly: “Not a problem in Mississippi, it is a major concern for growers in Florida and California, which have carried out extensive eradication programs. It has also been seen in Gulf coastal areas.”

• Balsam wooly adelgid: “A destructive pest of Fraser firs, it and the hemlock wooly adelgid, have had a huge impact on the landscape of the Smoky Mountains, with great swaths of dead and dying trees.”

• Emerald ash borer: “This one came into Michigan in 200s and has killed millions of trees across the north.”

• Asian bighorned beetle: “Found in New York state in 1996, it bores into non-oak hardwoods and eventually kills them.”

With the increase in global commerce, opportunities have increased for the introduction of many non-native species that can adapt to life in the U.S., Layton says. Some have no predators here and can quickly multiply and overwhelm an ecosystem.

“It’s important that we remain on the alert for these invaders. You never know when one will have the potential to be the next boll weevil, or even worse.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like