By now, it's no secret that agriculture is poised to see more benefit from unmanned aerial systems (UAS) technology than any other industry. However, in many cases, there's still the challenge of collecting quality, high-resolution imagery, understanding what it means, and turning that data into an actionable decision.

PUTTING BENEFITS TO USE: Agriculture is reaping great benefits from unmanned aerial systems (UAS), perhaps more than any other industry. Collecting high-quality, high-resolution imagery and understanding what it means can still be difficult, however.

That's where Justin Kyser, founder and CEO of DivviMap, hopes to come in. After earning his commercial pilot's license two years ago, Kyser founded Digital Sky, a UAS service provider focused on image-capturing. Kyser, who graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln this spring, recently founded DivviMap, which focuses on processing these data. DivviMap is one of the companies in this year's NMotion program, a Lincoln-based, mentor-driven startup accelerator.

"We found out farmers were having trouble just using the data because they couldn't access it where they needed it. They were tied down to their desktop computers," Kyser says. "The files are huge. If you look at a 160-acre field, we're talking between 1G [gigabyte] and 2Gs of data. That's a lot for anyone's computer to be able to handle. That's where DivviMap comes in. We thought, 'What if we could make this data portable?'"

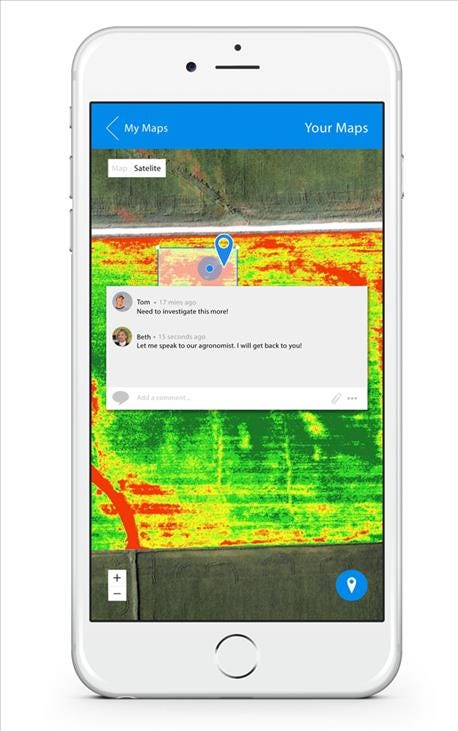

So, DivviMap developed a mobile app that allows growers to work with UAS service providers with a DivviMap subscription, which compresses large images into smaller GeoTIFF files growers can view on their phone. The process lets users load smaller pieces of a field on their phone at a time, using fewer mobile data while allowing them to see imagery on their phone within a few seconds.

CONNECTING TO THE FARMER: Using the DivviMap mobile app, Justin Kyser hopes to helps connect service providers with the end user, the farmer, in a new way.

Kyser says this helps connect the service providers with the end user, the farmer, in a new way. "The way we look at the industry is, we haven't seen enough farmers investing in higher-quality drones to use this yet, so we've tailored this to the drone service provider," he says. "They purchase this software from us, they go out and take imagery, load the map into DivviMap, and the farmer can view it on the phone. The farmer then has an easier way to manage all the maps he's getting."

Using these data, the grower could have multiple layers on one field with different GeoTIFF images, including normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), which measures green leaf area, near-infrared, visible-spectrum, or even hyperspectral imagery — depending on the kinds of imagery and UAS technology the service provider has access to, of course.

Using these kinds of data, Kyser notes there is potential for growers to identify problem spots in the field, and verify and diagnose the problem by ground-truthing. "The NDVI tells me this is a red spot. I can see this image, go out and identify exactly what's going on out in in the field," he says. "I can let my agronomist know and change anything based on this image now, because I have this verified data I've seen from the drone, and I've verified it in the field as well."

By adjusting management practices in-season and for specific parts of a field, these kinds of data could allow growers to do more with the same amount of land, and with fewer inputs.

"The overall amount of arable land is static. We need to get more efficient. The way to do that is data. If you can make fields more efficient without having to pour a bunch of money into it, it's better than running trying to find more land to farm," Kyser says. "That's what data's already doing. Ag wasn't really seen as a science back in the 1800s, but now there's so much technology that goes into growing corn or soybeans that you have to have some sort of data analysis to keep getting better."

For more information on how you can use DivviMap in your operation, visit divvimap.com/agriculture.

This article is the fourth in a web series on ag technology's role in Nebraska's Silicon Prairie.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like