December 12, 2014

Harper Armstrong knows he was lucky in 2014. Plenty of rain kept his irrigation engines turned off. And relatively milder temperatures helped prevent dreaded aflatoxin from invading his Bastrop, La., farm.

But he will be prepared each season for the potential return of the feared Aspergillus flavus fungi that causes aflatoxin.

He won’t be alone. Corn, cotton and peanut producers across the Mid-South, Southeast, and Southwest always face an aflatoxin threat due to the region’s climate.

High humidity, simmering summer days and drought can combine to breed the fungi. If it invades corn, any corn containing 200 parts per billion aflatoxin can’t be fed to beef cattle and other livestock.

If it tests at or above 20 parts ppb, the corn can’t be used in food products or fed to dairy cattle.

Many foreign buyers refuse to accept corn with 20 ppb aflatoxin. More than one shipload of corn has been turned away at foreign ports. And many farmers have seen truckloads of corn denied by grain elevators if it tests high in aflatoxin.

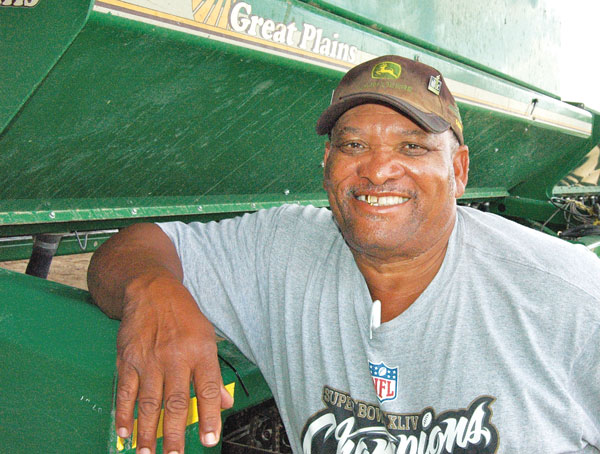

Armstrong farms about 2,400 acres of corn, soybeans, wheat and double-cropped soybeans in the northeast Louisiana region.

Aflatoxin has caused problems for him in the past — before he began using a granular anti-fungal crop protection product, Afla-Guard, approved for use on corn and peanuts.

“Corn has become more and more important to us,” Armstrong says. “We’ve had to worry about aflatoxin in the past. We scout the crop carefully to see if there are signs of aflatoxin or other diseases. Afla-Guard is helping combat the toxin.”

Combination of products

Spores of the non-toxic Afla-Guard fungus grow and colonize the field, which allows for efficient growth of the crop.

“Our corn yields are about 150 bushels per acre,” Armstrong says. “We started applying Afla-Guard and a fungicide in 2011, and we’re seeing a response in production.

“We sprayed Afla-Guard in 2014, even though we had good rainfall. We’ve had no corn to show up with aflatoxin. We’re also seeing better yields from Bt corn — kernels on top of the ear that earworms used to eat add up.”

Armstrong has farmed for 48 years in the Morehouse Parish region. In 2013, he was named Louisiana Farmer of the Year.

Technology improves production

He has taken advantage of technology to improve his production. When irrigation has needed improving, he has used specific conservation programs offered by USDA’s Natural Resources and Conservation Service.

Kira L. Bowen, plant pathology professor, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at Auburn University in Alabama, says the material in the aflatoxin control product “contains a strain of A. flavus that doesn’t produce any toxins, i.e., it is non-toxic atoxigenic.

“When this atoxigenic is applied to corn, the naturally-occurring aflatoxin-producing A. flavus strains are displaced by the introduced strain, and are less likely to infect the grain.”

She says aerial application of 20 pounds per acre of Alfa-Guard should be made just before tasseling and active silking occurs.

“Optimum results will be obtained if application is made when abundant moisture is available, such as soon after a rain or irrigation,” Bowen says. “While the product doesn’t prevent aflatoxin accumulation, toxin concentration in grain is greatly reduced.”

Timing can help

Timing of harvest can also help manage aflatoxin.

“Producers may reduce the continued accumulation of aflatoxin in corn grain in the field by harvesting before it reaches the industry standard of 15.5 percent moisture,” Bowen says.

“Corn reaches physiological maturity at about 30 percent moisture and can be harvested any time thereafter.”

She says there is also research that indicates the risk of aflatoxin contamination is consistently higher on the edges of a field.

“If a problem is suspected, it may be worthwhile to separate the grain from the field edges (8 feet to 10 feet inward) from the field center,” Bowen says.

Since ear damage by insects can contribute to aflatoxin problems, pest management in corn is important.

“There are a number of insects that may play a role in aflatoxin problems, such as stink bugs and weevils,” she says. “Bt traits only provide protection against lepidopteran pests, so they are inadequate to control aflatoxin.”

Armstrong says that in the event aflatoxin returns, he’s hopeful additional products will be available to fight the fungus. AF36 is one of those tools, but it’s only labeled for use in Texas and Arizona corn and cotton.

Scott Averhoff, a Waxahachie, Tex., grower and chair of the Texas Corn Producers Board, says there’s hope the Environmental Protection Agency will provide approval for use of AF36 across the South and in the Midwest.

“Growers would like to see more products available to help control aflatoxin,” he says, adding that new research is looking at additional aflatoxin control systems with multiple strains of fungi to fight the disease.

You May Also Like