January 21, 2020

Over the years, the conversation among conservationists and conservation-minded farmers in Iowa was about “tolerated soil loss” from erosion. The thinking was you could slow soil loss, but you couldn’t stop it. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service says on average, sloping soils in the state have lost half their topsoil. And the question was always when, not if, topsoil would be depleted.

That conversation was much different than the one Iowa NRCS soil scientist and soil health proponent Patrick Chase has today when he talks to groups of conservation-minded farmers about regenerating and building topsoil, rather than losing it.

“Scientists said it would take 300 to 500 years to build an inch of topsoil,” Chase says, “and unfortunately, as sloping soils were cropped, erosion stripped it away faster than that. But in the past 20 years, farmers like Gabe Brown of North Dakota have proven you cannot only stop soil erosion, you can actually rebuild an inch of topsoil in three to five years by practicing the five pillars of soil health.”

CHECKING SOIL HEALTH: Soil scientist Patrick Chase uses a spade, penetrometer, infiltration rings and other tools to get a reading on the health of soil.

Chase says these practices mimic natural ecosystems on the prairie that built Iowa’s rich soils in the first place. “Prairies were very diverse, with a variety of growing plants through much of the year to feed microbes in the soil, and they were grazed,” he says. “That’s what we’d like to work toward — soil that’s armored to maximize cover and minimize disturbance, with a diversity of plants growing as much of the year as possible. And where possible, graze the plants on a rotational basis.��”

Healthy soils are stable

“Soil that’s tilled falls apart with water,” Chase says. “In a healthy soil, microbes build soil aggregates with pore spaces that retain and exchange air and water. It’s really tough to feed microbes enough to build those aggregates if we have plants growing in the soil only four to five months out of the year with a corn-soybean rotation. I’d love to see a third crop in the rotation, maybe a small grain like hybrid rye that could be harvested early in the year. That would allow a multispecies cover crop to be planted. All those elements, with no-till farming and some grazing of those cover crops, would be a Cadillac system of soil building in my mind.”

Instead, Chase says, a corn-soybean rotation with tillage destroys the microbial life in the soil. “Fungi produce the glue, called glomalin, that holds soil aggregates together,” he explains. “Without that glue, the soil aggregates are not stable. When raindrops hit bare soil at 20 to 30 miles an hour, they displace the soil and it clogs pore spaces. Then we get runoff instead of infiltration. It can take an hour for half an inch of rain to infiltrate into a highly tilled soil. But in a healthy soil that’s been no-tilled with cover crops for a few years, anywhere from 6 to 10 inches can infiltrate in that hour.”

Short growth better than none

While Chase advocates for the Cadillac system of cover cropping with as much diversity as practical, with winter-hardy cover crops that extend growth into the spring, he says growing cover crops for even a few weeks in the fall can make a difference in the soil. Short growth of the cover crop in the fall is better than no growth. That is, it’s better than not seeding a cover crop in the fall and not having a cover crop in the field over winter.

“I’ve seen the difference even a week of fall cover crop growth can make,” Chase says. “That’s why more and more farmers are planting green, especially planting soybeans into standing, tall cereal rye that they let grow longer into the spring. They want to get the full benefit from that cover crop. But we shouldn’t discount what the roots of radishes, rapeseed, kale or oats can do in the fall. Those plants might winterkill, but their roots can feed microbes longer into the fall compared to nothing growing at all.”

Cereal rye standard cover

While cover crops aren’t being used on a high percentage of cropland, more farmers are trying cover crops, and cover crop acreage has steadily grown across the state. In 2009, Chase notes, a survey by Practical Farmers of Iowa showed an estimated 10,000 acres of cover crops in Iowa.

“A 2018 estimate by ISU Extension put the figure at 800,000 acres, so that’s a big increase,” he says. “And a lot of those acres aren’t being planted through government programs. About 60% of the people using cover crops now are planting them without any kind of government incentives.”

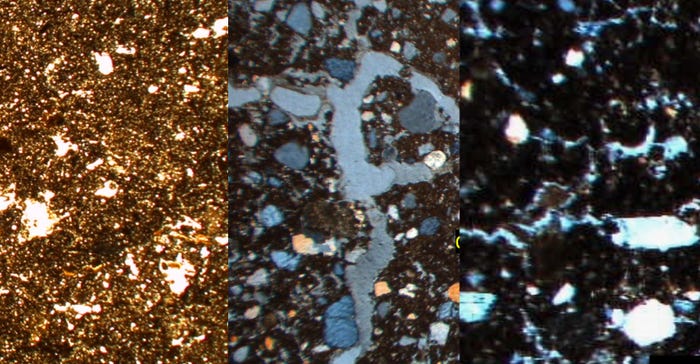

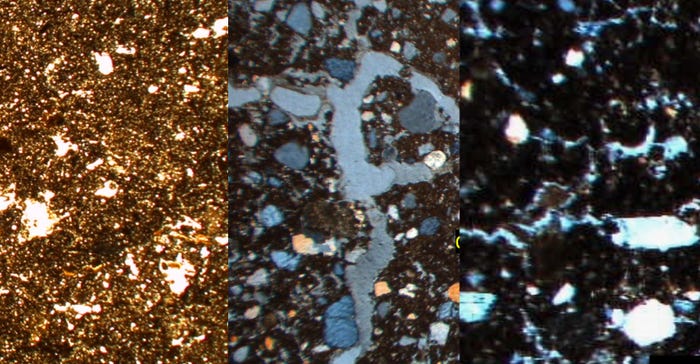

POOR PORE SPACE: The conventionally tilled soil on the left has very little pore space, while the pore space for air and water movement through the soil in the healthier no-tilled soil in the center looks much more like the virgin native prairie soil on the right.

By far, cereal rye is the most used cover crop. “It’s easy to work with, and it survives the winter,” Chase says. “Which species of cover crop you choose depends on your primary purpose. For instance, a typical nitrogen efficiency without cover crops is 30% to 50%. But that nitrogen efficiency — how much of it is used by the corn plant — can increase to 70% by using a cereal rye cover crop that takes in the nitrogen and then later releases it slowly for use by the corn plant.”

“If you’re looking to break up compaction, rapeseed has a taproot that can do that,” he adds. “The same is true of radishes. Some people are using winter wheat or triticale, and some are using oats. Annual ryegrass is a great plant to aggregate soils, and its roots will grow deep into the soil, but you have to watch it because annual ryegrass could be hard to kill if you let it grow too long. You don’t have that problem with cereal rye.”

Get started with cover crops

Chase advises trying cover crops or new combinations of cover crops on a small area and using test strips to check on what works and doesn’t.

“After six to eight years of no-till and cover crops — maybe not that long if you use cover crop mixtures — you can start taking credit for a healthier soil,” he says. “You can be thinking about cutting back on nitrogen fertilizer application, seed treatments and other inputs. You should see an increase in soil organic matter by that time and notice a much better rate of water infiltration into the soil than you had with tillage and no cover crops. Your soil should be crumbly and look like cottage cheese. This tells you that you’ve begun to regenerate and build topsoil.”

For information on cover crops and building healthy soil, visit nrcs.usda.gov.

Betts writes from Johnston, Iowa.

Build soil health, improve water quality

Rod Swoboda | Jan 21, 2020

Improving soil health plays a role in improving and protecting water quality. A publication, “Soil health in Iowa,” put together by the Center for Rural Affairs analyzes the impact healthy soils have on water quality, weather resiliency and farm productivity. Citing university and NRCS information, it shows how conservation practices, including grazing cover crops, can improve soil health and quality. Through better soil infiltration, absorption and carrying capacity, conservation practices create on-farm value for farmers. These changes also improve water quality by keeping nutrients on farm fields where they were applied.

“Better resilience during extreme weather events and a lower need for inputs like fertilizer are just a few of the benefits farmers see when they invest in soil health,” says Katie Rock, policy associate at the center. “The evidence is clear: Healthy soils result in long-term gains in productivity and financial stability of farms across Iowa.”

Policies supporting soil health will play a key role in meeting the goals of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, which aims to reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus in the state’s waterways by 45%. “As we encourage practices that can rebuild topsoil, farmers and their downstream neighbors will continue to see financial and recreational improvements,” Rock says. “Several studies of farms in the Upper Mississippi River Basin document cost savings of $100 per acre after they invested in soil health practices.” For more information, visit the Center for Rural Affairs.

Cleaner water with cover crops

Cover crops significantly reduce nutrient runoff in crop fields, according to tile drainage water monitoring results compiled by the Iowa Soybean Association. In 2018 tests at various locations, average drainage water nitrate concentrations were 23% lower in fields with cover crops compared to fields without cover crops.

“We’re seeing significantly less nitrate concentration and less loading in cover crop fields,” says Tony Seeman, ISA environmental research coordinator. “Without cover crops, we see a wide range of concentrations coming out of tile lines. Where there are cover crops, the concentration of nitrate coming out of the tile is more even. Those cover crops are working year-round.”

ISA researchers collected and analyzed 4,000 water samples from 613 locations across Iowa, including 335 tile drainage outlets. They also analyzed water samples from rivers, streams and conservation structures such as bioreactors, saturated buffers, ponds and wetlands.

ISA studies show it’s more important to identify the most effective practices for a particular field and landscape, rather than rely on a one-size-fits-all approach. For example, Seeman says a bioreactor in a field in Pocahontas County in northwest Iowa showed a 50% to 60% reduction in nitrate concentrations. In other situations, saturated buffers or wetlands have proven more effective. “The data we’ve collected can help us manage these practices better,” he notes.

Working across small watersheds, ISA research has documented positive results over time from coordinated efforts by farmers to reduce runoff. “Farmers who are using these conservation practices to reduce runoff are moving in the right direction, as they are also reducing nitrate concentrations in drainage water,” he says.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like