Each year, farmers take special care to select the best seed varieties. They also plan their fertilizer and chemical applications. But have they taken time to consider which soil sampling strategy is best for the farm?

Soil testing is the foundation for a well-planned fertilizer management program. To get accurate soil test results, you need soil samples that are representative of each field. You need to plan a soil sampling strategy to get those representative samples.

“Soil testing is the basis for developing a plan to control input costs by managing nutrient applications,” says Jim Friedericks, agronomist with AgSource Laboratories at Ellsworth, Iowa. “The challenge is finding what sampling method works best for you and tells you what you need to know, and then sticking with it.”

AgSource receives samples from all sizes of farming operations and from growers who produce crops ranging from corn and soybeans to wheat and alfalfa. There are some things to remember about soil variability and soil testing that can help you choose the strategy most suitable for your farm and manage nutrients wisely for greater profitability.

Select a strategy that fits

There are different ways to sample a field, but it’s most helpful to understand why you picked one strategy, and then use it to your advantage. Two common sampling strategies are grid and zone.

Grid sampling. Commercial soil samplers offer sampling densities, or grid sizes, from one sample per 5 acres to one sample per acre. The smaller grid sizes produce more detailed maps of the variability of the field.

“It’s like pixels in a picture,” says Casey Robinson, AgSource sales representative for Iowa. “The smaller the pixel, the better the picture.”

If the soil variability of a field is not known, such as on newly rented land, then the smaller grids offer the resolution you need to create useful maps for nutrient management, he notes.

Research from fields in Illinois showed that 1.25- and 2.5-acre grids generated maps that are similar to those produced from 0.1-acre grids. But larger grid sizes (5 or 10 acres) tend to mask, or blur, the variability and can lead to overapplication of fertilizer in parts of the field. When the field is known to be fairly uniform, or if there is a known management history of the field, then the larger grids provide enough detail for adequate management.

The larger grids will also be able to reveal changes in nutrient levels within the field over time. A typical grid sampling strategy is to collect sample cores from a specific point within each grid cell.

Zone sampling. With the availability of other spatially indexed field data including topography, soil series, aerial imagery and yield maps, this information can be used to identify zones in the field that can be grouped under the same management strategy. Sampling of these areas under a “zone,” or directed soil sampling plan, has the objective of getting an average soil test value for the area being sampled. In this case, the variability of the field is organized as a mapped zone that will be managed as a single unit.

Considerations when creating zones and a zone sampling plan:

• Segment your field into management areas based on specific field characteristics such as terraces, elevation or management history.

• Identify zones with similar characteristics in each area of the field. Similar zones may be located in separate areas.

• Other data such as electric conductivity mapping or manure application history can be used to identify zones.

• If zones are larger than 20 acres, then subdivide the zone for soil sampling. The results from these samples can be averaged for a uniform treatment.

Take a representative sample

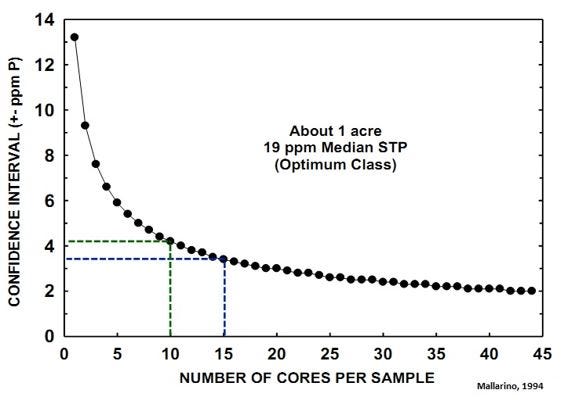

To accurately determine the nutrient content or soil test parameter of a given area, you need a representative sample. As the number of soil cores combined to create a sample increases from five to 10, the probability of finding the “true” value of the sampled area increases from 70% to 80%.

Increasing from 10 to 15 cores brings it to almost an 85% chance of finding the true value. Thus, 10 to 15 cores are recommended as the minimum number of cores per sample needed for reliable results, as illustrated for soil phosphorus in the chart below.

Be precise

Soil sample depth, placement relative to the row, and the consistency of pulling that same quality of sample each time is very important.

“There can be a lot of questions about the correct sampling technique to use in a field,” says Jacob Niewohner, AgSource Laboratories sales rep for Nebraska. “But the key is to be consistent when sampling a field, so when it is resampled in the future, the information can be used in the same way.”

Here are some considerations to keep in mind for consistent sampling:

• Avoid any “outliers” or significantly different field areas, such as terraces, field depressions, headlands, field entries or eroded spots during sample collection. These can generate results that aren’t representative of the rest of the area.

• Collect the same length of core at the same angle every time, and remember to combine and mix the cores before filling a soil sample bag with your representative sample. Typical cores are 6 or 8 inches long.

• Collect cores from at least eight locations relative to the visible rows in a field. If fertilizer has been banded, then collect one core for every 2 inches of row spacing and only one core in the row. This pattern should be followed even when the cores to be mixed together for one sample are collected from different rows and throughout a zone.

Mechanical sampling equipment has the advantage over manual sampling because the core is collected in the same manner each time. But making sure the cores are pulled with an adequate distribution across the rows is more difficult with the automated equipment.

Careful planning and consistent practices will generate the kind of information you can confidently use to get the right soil management practice onto the right place for better crop growth.

Source: AgSource Laboratories

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like