Nitrogen is a cost that Mike Braucher wants to minimize. He knows his corn needs it, but he’s keeping an eye on the bottom line. That means managing N the best he can on his 1,500-acre farm just outside Mohrsville, Pa.

And that process starts now.

“For us, producing the crop, we're going to start with residue management," Braucher says.

The chopping corn head spreads out the residue, helping to break it down so it becomes usable next spring as soil nutrients.

He rotates his corn and soybeans to improve disease and weed management and prevent resistance to sprays. When he gets in his cornfields next spring, he’ll put a little nitrogen out at planting and use a stabilizer to prevent leaching and volatilization.

“Everything we do has a cost to it, so we're going to try to limit our costs and then protect our costs,” he says. “So, by using the products that'll help the nitrogen remain in the soil where it's available to the plant, we want to protect our investment as much as we can, and we do that by using products that help it adhere to the soil and to the organic matter. And then by timing and then by product selection.”

Preventing N losses

Lots of factors lead to nitrogen losses, whether natural or manmade. When biological activity is active, nitrogen loss pathways are active, according to Eric Rosenbaum, owner of Rosetree Consulting LLC.

“It's our job that with nitrogen loss and managing that nitrogen loss to make sure that the manmade part is minimalized," he says.

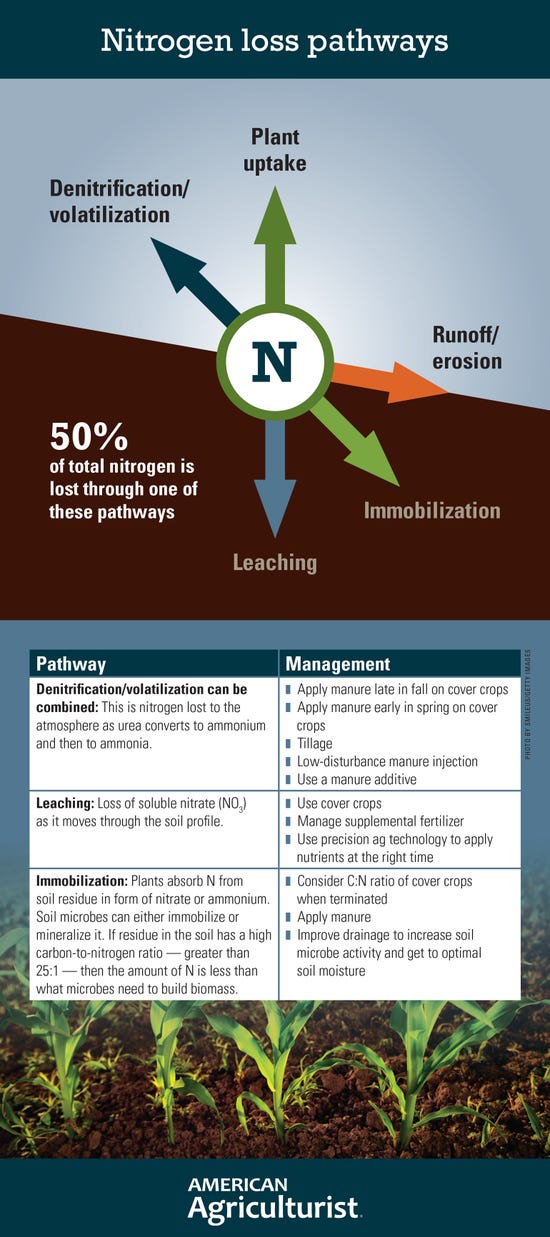

The goal of applying nitrogen is to make sure it gets to the plant, whether it’s from manure or fertilizer. And each day that goes by, there is always a chance that nitrogen will be lost through one of the following nitrogen loss pathways:

Immobilization. This usually occurs from heavy residue. For example, if you have heavy corn residue and want to go out and no-till corn, nitrogen can be immobilized in that residue because of its high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. In general, when residue has a C:N ratio greater than 25 to 1, the amount of nitrogen is less that what the soil microbes need to build biomass, so they pull the nitrogen from the soil, making it unavailable to plants.

One way to prevent this, he says, is to look at the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of cover crops when they’re terminated. Another tool is to improve drainage to increase nitrogen to the plants.

Leachate. This is the loss of soluble nitrates as it moves through the soil. Sandy are more prone to nutrient leachate.

Runoff from heavy rainfall and lack of cover crops can also cause leachate loss.

Denitrification. This occurs when nitrogen is lost through the conversion of nitrate to gaseous forms of nitrogen like nitric oxide, nitrous oxide and dinitrogen gas.

It happens most often when soil is saturated and bacteria use the nitrate as an oxygen source.

Volatilization. This is the most common nitrogen loss pathway. Think of surface-applied manure, where 80% of it volatizes into the atmosphere.

Rosenbaum says that around 50% of total nitrogen applied is lost through one of these pathways. In the more limestone and clay-based soils of Pennsylvania, volatilization is more of an issue, he says. So, he works with farmers on things that can prevent volatilization, such as applying bands of nitrogen at planting, using a nitrogen stabilizer and side-dressing later in the season when volatilization decreases.

Cover crops are especially important if you’re spreading manure or have corn silage acres, he says.

Manure injection is good for volatilization as well as tillage, so long as you incorporate the manure within 24 hours of application. But that 24-hour window is key, he says, as it can save money on nitrogen above and beyond the cost of tillage.

“The quicker you can work it in, there is more nitrogen to save. I usually tell people that if they can do tillage in 24 hours, that's their best bet to get it back,”, he says. But do it within the confines of your farm conservation plan.

A whole-system approach

Braucher, for the most part, rotates his corn and soybeans — though sometimes he does back-to-back plantings depending on the field. He also does 100% no-till.

The crop rotation helps improve disease and weed management by changing chemistries. He mostly uses synthetic nitrogen, though he’ll use manure from time to time.

His soil’s cation exchange capacity (CEC) is something that also drives his management. Soil particles are negatively charged and attract positively charged molecules like nutrients, water, herbicides and other soil amendments.

A soil particle’s ability to react with these molecules is its CEC. If the CEC number is low, it’s harder for molecules to bind (react) to the soil particle surface. If the number is high, a larger number of molecules can bind to the particle’s surface.

On his farm, the CEC levels are low.

“We need to spoon-feed our crop at our soils ... mostly what the soils can handle, but we want to get enough nutrients, especially nitrogen, on the corn crop that it maximizes the potential for that field and for that seed and variety,” he says.

Once he completes planting and applies some starter fertilizer, he’ll monitor the plant through tissue sampling and other testing. Once it gets to 3- or 4-feet tall, he’ll go in and side-dress if he needs to. He’ll even put on another nitrogen stabilizer not only to limit volatilization, but to also free up some nitrogen in the soil because he wants the roots to be able to draw it in as quickly as possible.

He doesn’t do much cover crops. Instead, he has winter annuals and targets insects and weeds through herbicides, pesticides, integrated pest management and scouting.

"We want to plant the longest relative day-length corn that we can because it makes a longer pollination window, makes it drought tolerant, and that's our biggest concern on our soil, drought tolerance," he says. The day length ranges from 104- to 117-day corn.

He’s not done though. Braucher plans on increasing his variable-rate nitrogen applications and wants to fine-tune the types hybrids he’s using in certain fields.

This year he experimented with soil biologicals and he’s mapped where those soil biologicals have been applied.

For Braucher, proper nitrogen use isn’t just about saving money or increasing yields, it’s about profitability and how it applies to his whole farming system.

Read more about:

NitrogenAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like