Greg Busch has a new farming mission. When he began farming on his own in 1980, his mission was to leave the land in as good or better shape than when get got it.

“As time went on, I could see that I could do a lot better than that,” he said.

With the technology that’s was available today, the Columbus, N.D., farmer believes that he can restore the soil to its virgin prairie condition.

“That become my mission now,” he said.

Busch, of Columbus, N.D., farms with his spouse, Jessica. He spoke at the 2020 Farming for the Bottomline Conference sponsored by the USDA ARS Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory, the Natural Resources Conservation Service in North Dakota and several other organizations.

First no-till

“I started with a degraded soil,” said Greg, who began farming with his father, Francis. “That really wasn’t my grandpa’s fault. It really wasn’t my dad’s fault. They worked with the technology they were afforded in those days.”

They were in a wheat-fallow system, the predominate production practice in the western Dakotas at the time. The farm’s soils had just 1% to 1.5% organic matter. They dried out every summer and were being eroded by wind and water.

“And we weren’t profitable,” Greg said.

In 1978, Francis — who was about a year from retirement — did a no-till trial on 80 acres.

“I was the naysayer,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Dad you can’t do that. It is going to look like hell.’ And he said, ‘I don’t care. let’s just see what it does.’”

INTERCROPPED: Greg Busch examines flax and chickpeas, which he planted as companion crops.

INTERCROPPED: Greg Busch examines flax and chickpeas, which he planted as companion crops.

The result was not great, Greg said, but he and his father considered it to be a success. No-till worked. It took Greg until 1985 to embrace no-till, and he has continued the practice through today.

In hindsight, Greg said his no-till management was pretty simplistic.

“I just grew cereal grain and applied way too much fertilizer,” he said. “We did see some good things [from no-till], but our soil organic matter plateaued at 2.5%.”

Financially, no-till helped them a little.

“We were making more money, but we still weren’t very profitable,” Greg said.

Biodiversity drive

In 1992, they began adding more crops to the rotation. Other no-tillers and Dwayne Beck, manager of the Dakota Lakes Research Farm near Pierre, S.D., were advising farmers to add biodiversity to improve soil health.

“In all, we’ve grown over 20 different crops,” Greg said.

Now, they usually grow eight to 10 different crops each year. Field peas, canola, flax, spring wheat, sunflowers, soybeans and oats are mainstays.

Increasing the number of crops in the no-till system changed the soil.

“Organic matter started creeping up and the number of earthworms in the soil, the amount of water the soil absorbed, and the soil structure improved,” Greg said.

Cover crops added

In 2010, the Buschs started planting cover crops. Their goal was to have living roots in the soil and a cover on soil surface for longer during the year.

Today, they try to plant at least a five-way cover crop mix. They keep the cost of cover crop seed low by using leftover seed — flax, oats, and rye — whatever is bin, Greg said. They buy radish, turnip and clover seed because they don’t grow those crops.

STORED TOGETHER: Greg holds a handful of field pes (large seeds) and canola seeds that he stores together.

STORED TOGETHER: Greg holds a handful of field pes (large seeds) and canola seeds that he stores together.

In 2018, they began intercropping. They grew field peas and canola together in the same field at the same time. They also tried flax and chickpeas together.

In 2018 and 2019, yields from growing the two crops together were more than growing them separately. Costs were lower, too. They didn’t have to fertilize canola or flax because the field peas or chickpeas fixed enough N for themselves and their companion crop. They didn’t have to spray chickpeas with fungicide to protect the crop from Ascochyta blight.

Often, chickpeas in a monoculture have to be sprayed several times to keep them healthy. Field peas — especially Maple field peas, which are tall but prone to lodging — used the canola plants as trellises. It was easier to harvest the intercropped field peas, and the combined yield was higher than monocropped field peas.

Organic matter and profits

Now the Buschs’ average soil organic matter is starting to approach 4%. Their profit margin has improved, too. No-till has cut their fuel use to 1.8 gallons of fuel per acre. They don’t need any heavy tillage implements or big tillage tractors in their equipment lineup anymore. They are using 30-40% less fertilizer than in the 1980s.

Labor needs are also down. Greg and Jessica do nearly all of the fieldwork on their 5,000 acres themselves. They sometimes have fertilizer custom spread and Greg’s brother helps them with harvest for about 7-10 days each fall.

Next steps

Greg’s next steps in his mission to restore their soil include:

Reduce use of Roundup Ready crops. Greg wants to conserve glyphosate for pre-plant burndown, an important practice in no-till. Other postemergence herbicides can be used in crops, he said.

Reduce monocultures. Once they can buy multiperil crop insurance for intercropped fields they won’t likely grow canola, flax or field peas separately. It takes three years of history before special written agreements for intercropping can be applied for.

“Eventually we may intercrop or relay crop everything,” Greg said.

Plant more high-carbon, warm-season crops such as corn and millet. They need higher residue crops in rotation because the biological activity in the soil has increased so much that they are not able to keep the ground covered after growing two low-carbon species back to back, Greg said.

Bring in more livestock. The Buschs don’t own cattle, but they have had a neighbor graze his cows on their land. The animals seem to add a significant amount of nitrogen to the soil and they appear to increase the biological activity in the soil, Greg said.

He and Jessica did a fertilizer strip trial on field where the cows grazed the cover crop in 2016. The following year, their fertilizer applicator applied rates of 230, 170, 115, 60 and 0 pounds of urea per acre in strips across the field. They didn’t see any difference in plant growth or yield across the strips.

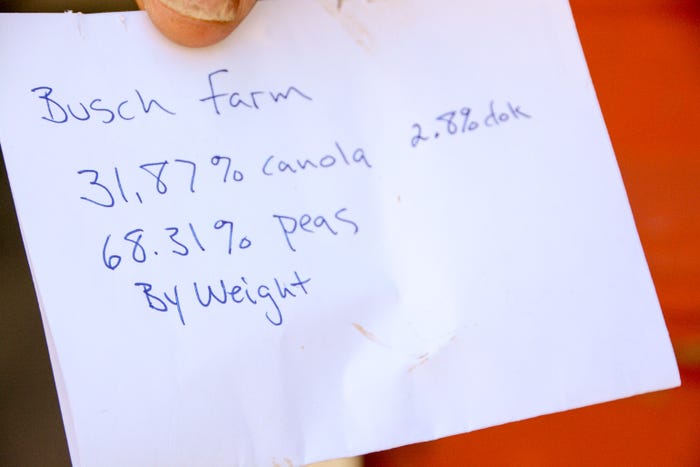

PERCENTAGE BREAKDOWN: A grain elevator analysis shows the percentage of field peas and canola in one of Greg Busch’s intercropped samples.

PERCENTAGE BREAKDOWN: A grain elevator analysis shows the percentage of field peas and canola in one of Greg Busch’s intercropped samples.

More testing is needed to confirm the results, Greg said, “but I think we could have saved a lot of money on fertilizer.”

They plan fence cropland and install livestock waterers. In the future, they could set aside the fields every fourth or fifth year, plant a full season cover mix and then graze it, Greg said.

More information

Learn more by watching Greg’s full 2020 Farming for the Bottomline Conference presentation below.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like