“The nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself.” — Franklin Delano Roosevelt

“…civilization itself rests upon the soil.” — Thomas Jefferson

Farmers understand that soil health is the building block of every successful farming operation.

The objective, however, is to maintain the perfect balance between moisture, decaying plants, minerals, and microbial residues — what agronomists call soil fertility. Making certain that soil has the proper elements for good nutrition represents an important step in the pre-planting process.

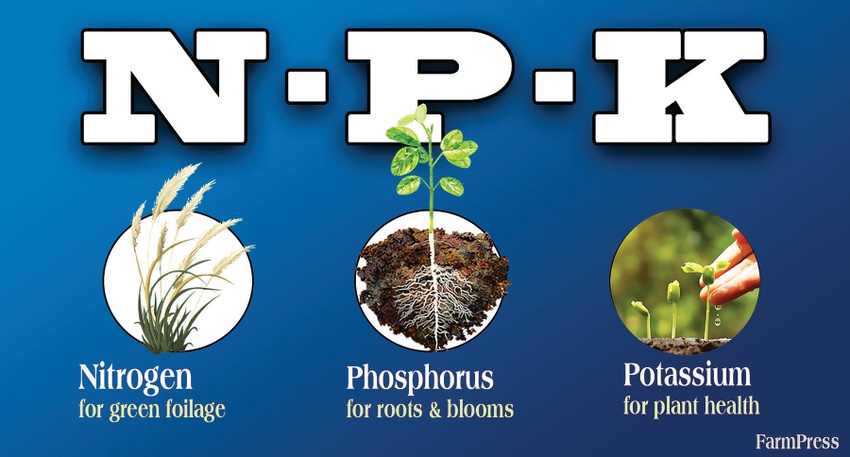

The many elements of soil fertility include soil pH, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur, iron, copper, boron, zinc, and molybdenum.

In general terms, farmers will only be concerned with three basic elements of plant nutrition: soil pH, nitrogen, and to a lesser extent, phosphorus and potassium, or P and K.

“The thing we recommend that every farmer do is to keep a current soil sample from the field,” says Dr. Angela McClure, University of Tennessee Extension professor and agronomist. “They need to have some idea of nutrient levels and ideally test at least every other year to determine pH and the P and K levels.”

WHERE TO BEGIN

Test the pH of the soil —

The starting point in soil fertility, McClure says, is determining the pH of the soil, which is critical because proper pH helps some macronutrients and micronutrients in the soil to function.

A pH imbalance can prevent the plant from doing a good job with the other elements farmers may apply to improve soil fertility. She recommends soil testing in the fall because warmer weather is best for testing pH, P, and K, and even sulfur, if that is a suspected problem. A 4-inch to 6-inch sample should be sufficient, though deeper soil sampling may be desirable if testing for sulfur or other mineral elements.

Dangers of pH imbalance —

Researchers warn that a significant drop in soil pH will result in soil acidity. Aluminum toxicity could occur when soil pH levels drop below 5 parts per million (ppm), and could affect plant root systems.

Dr. Darrin Dodds, Mississippi State University Extension cotton specialist, prefers the pH level to be at least 5.5 ppm for cotton, but ideally he would like to see 6.5 ppm.

“In Tennessee,” McClure says, “we have a variance in soil types. In the western reaches of the state, many soils are more acid, and in central Tennessee more neutral, so that would determine the need for pH adjustments. Keeping an eye on the pH level is a starting point and a key component in maximizing soil health.”

Nitrogen —

Testing generally is not recommended. Nitrogen levels vary across the year, making it difficult to know at any given time whether levels are high or low enough to justify additional applications.

Agronomists across the Delta region generally say pre-plant applications of N should represent approximately one-third of the annual N budget. An application of about two-thirds can be applied as a side-dress during the crop year.

Residual nitrogen can generally be found on both low-yielding and non-irrigated fields following a drought year. In such cases, as much as 40 pounds per acre of nitrogen on the top 10 inches of the soil may be available to support nitrogen needs for the next planting year.

“When addressing the needs of nitrogen in cotton in the Delta, I generally think that if you're growing in some of the alluvial soils of the Delta, around 80 to 100 pounds per acre would be required,” says Darrin Dodds. “If you’re rotating peanuts or corn with cotton, I would probably go on the lower end of that, about 80 pounds of nitrogen. But when growing cotton on cotton, I would use 90 pounds to 100 pounds. If you are growing on heavier clay soils I might go 120 pounds per acre.”

Too much N —

Dodds cautions that with too much nitrogen farmers typically are going to have a lot of rank growth, and plants will not respond well to growth regulators. Also, plants could get too tall, and defoliation is more difficult. In such cases, it is too late in the growing season to reverse the process, but it is a sign for growers to use less nitrogen the following year.

Phosphorus (P) —

Phosphorus plays a role in photosynthesis, respiration, energy storage and transfer; cell division, cell enlargement, and several other processes in plants. A plant must have phosphorus to complete its normal production cycle: Stimulated root development; increased stalk and stem strength; improved bloom formation; uniformity and early maturity; crop improvements; and resistance to disease.

Potassium (K) —

Potassium, the third most important element for healthy soil nutrition, can greatly increase crop yields under the right circumstances. It aids water absorption and retention in plants, and encourages strong roots and sturdy stems. Potassium aids the plant in preventing heat damage and in preventing some diseases.

Additional N, P, & K considerations —

Dr. Todd Spivey, Louisiana State University assistant professor, works with soybeans, and warns that initial application of nitrogen is often made before a producer makes a final decision on what type of crop he is going to plant.

It’s not unusual, he says, that a change in plans will slow the planting process, and a different crop may require less or more nitrogen than the original crop required. Under such circumstances, input costs can increase unnecessarily.

For soybeans, Spivey says, nitrogen fixation is, “for a lack of a better term, a lazy process.” If nitrates are in the soil, bacteria might not fix nitrogen to its fullest ability, and could delay nodulation in the crop. Because of that, he says, some farmers are reluctant to use a little aluminum sulphate because they are concerned about the effect it might have on nitrogen.

“But mostly, the amount of nitrogen being used across the Delta is not going to hinder nodulation to the extent that we will see any ill effects from it,” Spivey says.

Dr. Jason Kelley, University of Arkansas Extension agronomist, says except for nitrogen, a soil test is the only way a producer can determine soil fertility requirements. He recommends soil testing every other year, or every third year at a minimum.

“Fertility and seed represent a major portion of total input costs on the farm,” Spivey says, “so if we spend more on fertilizer than we should, it could mean the difference between profitability and no profit at all. Knowing your fertility needs, through a good soil test, is absolutely needed to address those types of problems.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like