Agriculture in what we call the developed world is based on killing what we have convinced ourselves are malevolent organisms.

The list of such candidates is extremely long. Everything from the smallest microbes through most of the plant kingdom and good portions of the animal kingdom are routinely condemned as harmful pests fit only for extinction.

Attempting to eliminate weeds, insects, pathogens, fungi and predatory animals consumes countless manhours and billions of dollars every year. Despite the "miracles of modern chemistry," most of the targeted organisms not only survive but thrive. Short-term results often appear to be favorable, the bug, weed or coyote died. There have been many apparent short-term successes of this sort through the years – DDT, 2,4-D, low-level feeding of antibiotics – but between target organisms developing resistance and side effects of the treatments being as bad or worse than the treated malady, the kill-the-pest approach seldom, if ever, cures the problem.

Quite frequently, the cure creates real problems that have severe and long-lasting effects. Tillage is an example. Plowing to kill vegetation, to prepare a seedbed, or to relieve compaction introduces large amounts of oxygen deep into the soil, oxidizing soil organic matter and thus reducing the ability of the soil to take in and hold water. The loss of organic matter has multiple ill effects. Soil life and its’ beneficial actions – biological, mechanical and chemical – is destroyed every time the soil is disturbed. As soil organic content and soil life is lost, production drops. This calls for more inputs of the exact kinds (tillage and poisons) that caused the problem.

Here's the punch line: Killing pests doesn’t work because the pests are not the real problem but rather, only symptoms of deeper under lying problems.

On degraded areas, weeds proliferate because they are better suited to these conditions than are higher-successional plants. Weeds are nature’s attempts to correct, or at least not make worse, poor growing conditions. Poor growing conditions are caused by damage to the ecological processes: The water cycle, mineral cycle and energy flow. Most of the tools commonly used in modern agriculture, things like monocultures, tillage, insecticides, herbicides, rapidly available fertilizer and continuous grazing, damage long-term growing conditions and cause pest outbreaks.

Many years ago, when I was following university recommendations, I sprayed my pecan trees early in the season to kill casebearers. In two weeks, aphids would be swarming the trees, forcing me to spray again. Spraying killed the casebearers but also killed the predator insects that kept aphids and other pests in check.

When I stopped spraying and changed my management to increase rather than to reduce the number of species present – to increase biodiversity – pest populations of all sorts were reduced. I still had casebearers, ragweed and horn flies but in much lower numbers. This was brought about not by killing pest organisms but by improving long-term growing conditions.

The most misunderstood of these long-term conditions is biodiversity. Nature develops a very effective system of checks and balances if we don’t interfere. Competition plays a role, particularly in the early transition from a degraded to a healthy ecosystem, but much more important are the multitude of mutually beneficial relationships that form when biodiversity is high.

Simple ecosystems like corn fields and clean Bermudagrass pasture are inherently unstable. In simple systems, large numbers of individual organisms are competing for the same set of resources, while other resources go without use. Consider a clean Bermudagrass pasture: Throughout much of the South, Bermudagrass makes full use of available sunlight for 90 to 100 days in late spring and early summer. The sunlight that falls in the other 265 to 275 days is largely lost to the system.

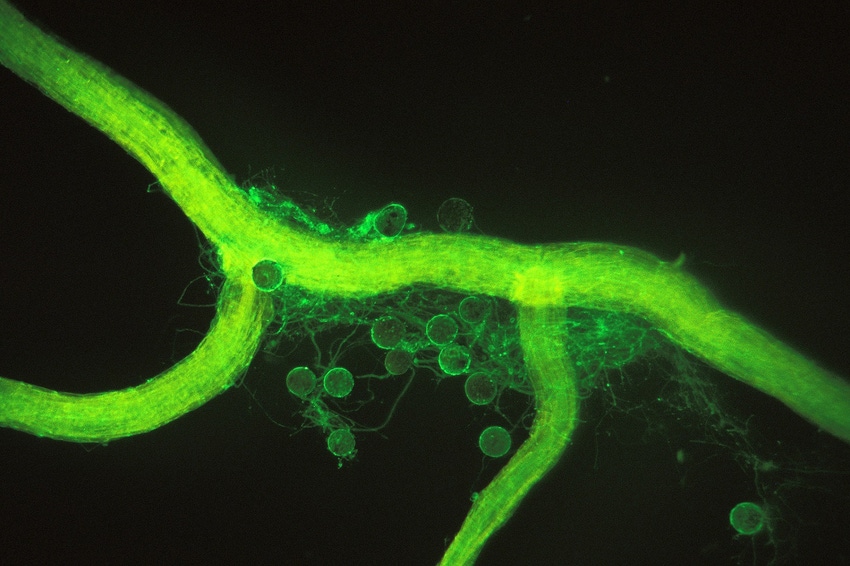

Cultivated crops like corn, even when no-tilled, are even more wasteful since prolonged periods without green plants destroy the mycorrhizal fungi that is so valuable to the entire soil-plant-animal-wealth-human complex.

We would be better off financially, ecologically and in human wellbeing if we changed from a production model based on killing to one designed to promote life. For a more complete discussion of the value of biological capital, see Biological Capital under the heading of "articles" at my website.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like