Building soil health, profitability and soil fertility is not something that happens overnight. For Scott Heinemann of Winside, Neb., the transition from feeding cattle and conventional no-till corn and soybeans to a new system that adds small grains and cover crops is more of a marathon than a sprint.

Heinemann comes from a family of cattle feeders. Following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, Heinemann fed between 400 and 500 head annually and hauled manure on his fields for fertility. But he used to till the land, too.

In 2006, Scott and his wife, Pam, did some soul searching about the future of their operation. They decided to get out of cattle feeding and add diversity and cover crops to their systems.

"We debated about whether to expand in the cattle or to farm more ground, but both options would have required a lot of expense and investment, just to make extra income so we could pay full-time hired help," Heinemann says. "It was a tough decision, but in the end, it was a good decision for us."

Heinemann had diversity when he had cattle, cutting silage and planting rye as a cover into the stubble. "We raised corn and soybeans, but we knew we needed to be more diversified," Heinemann says. "We decided to add small grains back into the rotation to allow us to plant a diverse summer-seeded cover crop. Although we don't have cattle now, there are a lot of young producers wanting to come back to the farm, and they like livestock. We were able to rent our grazing acres to those farmers, to the benefit of both of us."

The changes Heinemann made to his farm are significant, but he admits that he is trying new things to see what works and what doesn't. Here are four strategies he is studying:

1. Relay soybeans. This spring, Heinemann experimented with relay crops of cereal rye, broadcast planted last fall, and soybeans, planted in 20-inch rows into the growing rye on May 19. The idea was to harvest the rye for grain in July before the soybeans got tall enough to be pruned with the combine header. Heinemann was hoping the two crops would be more profitable than soybeans alone, because of the soil benefits and weed suppression potential of rye.

"The results this year were kind of disappointing," Heinemann says. "But I've identified some mistakes that can be avoided in the future." The rye yielded 17 bushels per acre, and the soybeans yielded 27 bushels. "It doesn't pencil out as well as soybeans alone, but with the savings in herbicide costs, it is closer than one would think," Heinemann adds.

Those who are having success with relay crops plant a longer-maturity soybean variety and then modify their combine header to push soybeans gently down while harvesting rye.

"This allows for shorter stubble height, without pruning the soybeans," Heinemann notes. "I also plan to plant a bush-type of soybean next year into rye that was drilled — not broadcast seeded — this past fall."

2. Shorter-season corn. Heinemann began to plant shorter-season corn on his dryland farm to test yields and provide more opportunity for interseeded cover crops to flourish. The 93- to 101-day corn varieties he plants, for example, allow him to gain yields of about 170 to 200 bushels per acre without worrying about drydown.

"My goal is to eliminate herbicides, or at least use as little as I can," he says. This practice avoids any risk of interseeded buckwheat or other cover crops growing too much biomass into the cornfields and compromising harvesting operations late into the season. Cover crops that grow forages after harvest when the corn plants are removed provide more grazing opportunities for cattle in late fall and winter months.

3. Grazing crops and small grains. "Cereal rye is my favorite herbicide," Heinemann says. He plants rye in the fall and harvests it for grain in midsummer. He then seeds a grazing crop mixture into the rye stubble. This diverse mixture may include sunflowers, sunn hemp, radishes and turnips, among others. A neighbor brings cattle into those plots to utilize the forages and cycle nutrients back into the soil.

"I just love to go out and look at the soil in those fields," Heinemann explains. "You can pull up some of the plants and see the numbers of earthworms." For Heinemann, these fields provide major soil health benefits, a rye grain crop and grazing forages for farmers with cattle.

To make this strategy work, the custom grazer must share Heinemann's goals for the land and be willing to follow his management requirements. "You have to get the right person with cattle to manage the grazing closely, and they have to be willing to check on the cattle and grazing conditions regularly," he says.

4. Wildlife plots and "chaos" gardens. "We love to see wildlife," Heinemann explains. Wildlife plots, which are located around the borders of several fields, are planted to wildlife-friendly species. Last season, Heinemann planted a tenth of an acre that yielded 150 pumpkins.

"The cows loved them and cleaned them up," he says. "We planted a chaos garden with all kinds of different crops, and we planted a pollinator mix next to the chaos garden. These plantings included safflower, buckwheat, sunflower, sudan and others." Corn is planted into these plots in the spring to study how the crop responds the following year.

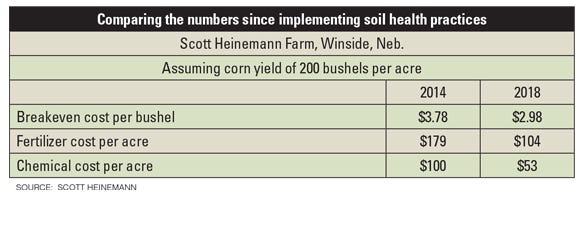

In addition to boosting soil health, the financial results of Heinemann's practices have been promising. He has lowered his breakeven price on corn from $3.78 per bushel in 2014 down to only $2.98 per bushel in 2018, assuming yields of 200 bushels per acre.

He has cut input costs considerably, lowering fertilizer expenses from $179 per acre in 2014 to $104 per acre in 2018. Chemical costs dropped from $100 per acre to $53 per acre in the same four-year period. Costs dropped to $50 per acre in 2019.

One of the reasons for lower expenses was that 2014 was the last time Heinemann used fungicides and foliar fertilizers, along with herbicide. Fertilizer use has dropped to 0.36 pounds of nitrogen per bushel of corn produced on his best fields in 2019, and 0.6 pounds of N per bushel produced average across the whole farm.

Soybeans have seen similar gains because of increased weed control from cover crops and his trend of lowering his seeding rate without giving up on yield. Herbicide costs on soybeans have gone from $56 per acre in 2014 down to $32 per acre in 2019.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like