November 6, 2018

---------

Think Different

The best way to learn is to be willing to try something new. If you test an idea carefully on just a few acres, it doesn’t matter if the idea succeeds or fails, Jack Boyer believes, because you learn either way.

-----------

Jack Boyer takes a scientific approach to building soil health. For the past 10 years, the retired ag engineer has focused on optimizing cover crop benefits on his farm, learning from both successes and failures of test strips on his farm near Reinbeck, Iowa. Boyer has worked with Practical Farmers of Iowa, the Iowa Soybean Association, Iowa State University and others to test the best ways to integrate cover crops into his seed corn, commercial corn and soybean operation. He and his wife Marion operate a 1,000-acre Century farm and grow their own cover crop seed.

After 10 years of testing and observation, Boyer’s takeaways include:

1) My top 3 reasons for using cover crops are erosion control, building organic matter, and increasing nutrient availability.

2) Erosion is expensive. I’ve been told the average 7.6 tons/acre soil loss per year in the U.S. amounts to a $40/acre loss in nutrients. That cost alone can justify using cover crops along with no-till or strip till for stepped-up erosion control. Soil erosion has both short-term and long-term economic consequences—everything from nutrient losses short term to loss of land value and decreased production long term.

3) Plant cover crops earlier if you want to capitalize most on the nitrogen sequestered for the next cash crop. Good growth in the fall translates to better growth in the spring. I’ve seen first-hand more N is available for the next cash crop—my average has been 66 pounds more N available with cover crops than without. The potential value is from $29 to $36 an acre for that N.

4) Cover crops can suppress weeds, to the extent that it’s possible to save enough money on herbicides to pay for cover crops while you keep fields just as clean. Cover crops cost about $30 an acre, but that’s not as costly as $40 an acre to spray herbicides. In one of my tests, in-season weed control was achieved entirely with the cover crop mulch, whether it was rolled or left standing. The most interesting part of that trial was the improved control of waterhemp in the cover crops versus no covers. I will say, though, the first time you plant green, it’s an emotional experience!

A strip test comparison of rolled rye (left CC302) and standing rye (right CC301) showed little difference in weed control or yields (without herbicides), but Boyer said both improved control of waterhemp better than strips with no cover crop.

A strip test comparison of rolled rye (left CC302) and standing rye (right CC301) showed little difference in weed control or yields (without herbicides), but Boyer said both improved control of waterhemp better than strips with no cover crop.

5) I see no yield differences in soybeans with and without cover crops after 3 years of trial data comparing the two. I haven’t observed any yield differences in corn, either.

6) You can plant green without any soybean yield consequences. After comparing four years of planting green against earlier cover crop termination, I haven’t seen any yield differences in soybeans. I haven’t had any trials for corn.

7) I’ve been applying too much nitrogen. Indicators last year showed I could cut the nitrogen I apply by 25 units without sacrificing corn yields.

8) I haven’t experienced allelopathy. There’s a lot of talk about allelopathy resulting in lower corn yields with rye cover crops, but I’ve never experienced it. I believe the key to fixing what some think is allelopathy is addressing N tie-up early in the season. I put 30 units of N in burndown to prevent N tie-up.

9)� Anhydrous doesn’t mean the end of earthworms. I’ve watched as anhydrous ammonia fertilizer killed earthworms in the 6” space where it was applied, but then I’ve seen them back in the area in eight weeks.

10) Interseeding cover crops at V4-V6 corn stage should work. I’m on a mission to see which cover crops will survive in interseeded commercial corn, in early corn growth stage. This year, I’m comparing a 60” row spacing on three acres of corn to 30” rows, with the same plant populations, to see if I can harvest more sunlight with both cover crops and corn. We’ll see what happens with yields.

Costly erosion: $339/acre

Statistics on costs of soil erosion show why Boyer ranks erosion control high as a reason to use cover crops. An NRCS report of their Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) from 2002 and 2010 indicated that each ton of soil eroded contains the equivalent of 2.32 pounds of nitrogen and 1 pound of phosphorus. The cost per pound for nitrogen and phosphorus were $0.63 and $0.64 respectively.

In 2012, Iowa State University Extension Economist Mike Duffy suggested that the real cost to the farmer based on those estimates was a loss of fertilizer at $2.10 per ton of soil loss per acre.

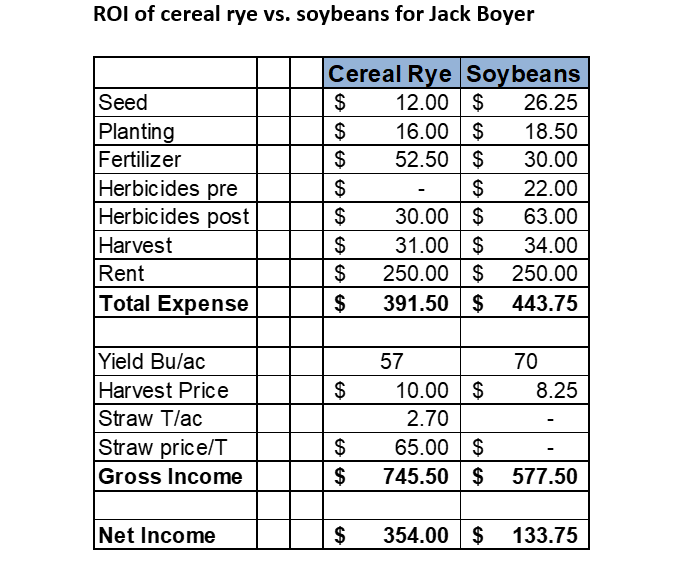

In 2016, Boyer found his ROI was much higher growing cereal rye for sale than soybeans that yielded 70 bushels per acre. He cautioned that it only worked because there was a market for cover crop seed, however.

Based upon July 2012 Iowa farmland values, Duffy also concluded that estimated loss in farmland value caused by soil erosion—based on crop suitability ratings—ranged from 3% to 17%. The average loss in land value per unit change in CSR value was 4.9%, or $339 per acre.

Lost farm income as a result of soil erosion in the U.S. is estimated by USDA at $100 million per year. Offsite costs of soil erosion go beyond the cost of lost fertilizer, loss of crop production and land value figured into lost farm income. When damages to roads, bridges and other infrastructure, environmental damage to streams, rivers and lakes, and other offsite costs were included, a 1995 assessment estimated the annual cost of soil erosion for both on-site and off-site effects at $44 billion a year in the United States.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like