Think DifferentIf you’d spent decades conducting seed-treatment experiments like researchers Ray Knake and Tristan Mueller have, you might see seed treatments in a new light forever. You’d no more want to miss insuring early seedling health than you’d skip your children’s immunizations.Seed treatment is all about reducing risk, especially in the first 72 hours of a plant’s life. And farmer use is proof. Aided by newer systemic fungicides and insecticides, their global sales more than tripled from $700 million in 1997 to $2.25 billion in 2010, and they’re estimated to reach $3.4 billion in 2016.

January 30, 2014

High yields begin with a uniform, healthy plant stand. “You can help this with protective seed treatments,” says seed-treatment expert Ray Knake, Ray Knake Consulting, who has more than 40 years in the business.

Earlier planting dates, reduced tillage and a compressed planting season have driven the seed-treatment sales boom, he says. “Maximum yield potential begins with a uniform, healthy, optimal stand. But wet, cold soils harm seeds and seedlings, especially during their first 72 hours, he says.

“If everything’s ideal, seed treatments don’t bring a lot to the table. But you see the difference in times of stress, with cold, wet conditions,” Knake says. “In 2013, we saw it in side-by-side field comparisons. There’s no rescue treatment available for below-ground pest control after planting with saturated soils and sudden soil-temperature drops.”

And while crop residues protect the soil, they can result in colder soils, Knake adds.

Higher input and seed costs almost mandate that you protect seeds and young seedlings, Knake says.

Seed-treatment choices

A corn grower doesn’t have many seed-treatment choices, Knake says. “Your seed company has decided what will be on its seed—it’s a blanket treatment. You might have a choice on a higher insecticide rate than the base treatment, and you could order a nematode control, but that’s about it.”

Soybean treatments have many more choices, for insecticides, fungicides and Rhizobia inoculants, Knake says.

He believes the whole package is best because it reduces risk. “Planting earlier, planting quickly, using crop residues—all favor seed treatment.”

Tristan Mueller agrees with him. He’s a program manager who helps coordinate on-farm evaluations for the Iowa Soybean Association’s On-Farm Network who previously worked with seed treatments. “Generally our on-farm trials haven’t shown large differences between seed treatments on corn or soybeans, but there’s a reason both are treated,” he says. Reduced corn stands do not compensate like soybeans—you’ll lose yield, he adds. “The trend is toward soybean treatment. I’d recommend treating most of your soybeans with a fungicide and an insecticide to reduce the risk of replanting. And I believe there’s a good chance of the treatment paying for itself in higher yields because of better stands and plant vigor.”

Ohio State University Plant Pathologist Anne Dorrance, and entomologists Ron Hammond and Andy Michel, have found success with seed treatments in soybeans during the all too common wet years. But if they could predict a dry year like 2012 they would say, “don’t treat your seed at all.”

In their research against water molds using metalaxyl and mefenoxam, they recommend the high rates to save stands and stop replanting, which deliver yield gains come harvest. They found this to be true in poorly drained fields, in no-till, in continuous soybeans and in a corn-soybean rotation.

When looking at the Strobilurins, the researchers find some helpful activity on some Pythium diseases, and good help with seedborne Phomopsis. fludioxinil (Maxim) has shown excellent activity on Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Sclerotinia and Phomopsis. Sedexane, a new mode of action, has good activity on Rhizoctonia. Ipconazole has good activity on Fusarium and Rhizoctonia. Penflufen is also good on Rhizoctonia.

See more details of their recommendations, including insecticide seed treatments.

New treatments for SCN and rhizoctonia

A new nematicide with season-long activity against SCN will be added to last year’s new Vibrance fungicide against rhizoctonia as part of Syngenta’s new triple pest protection seed treatment in 2014, with the introduction of Clariva Complete Beans nematicide/insecticide/fungicide.

“Soybean growers in the Midwest have told us their No. 1 problem is controlling cyst nematode, and that’s what has been missing in seed treatments,” says Wouter Berkhout, soybean product lead at Syngenta Seedcare. Vibrance was introduced for soybeans in 2013 (coming for corn in 2015).

DuPont Pioneer will continue to offer growers the same Pioneer Premium Seed Treatment program for 2014 planting as it did in 2013 in both its corn and soybean seed products. That includes EverGol Energy fungicide, (introduced in 2013) with enhanced protection against a broad spectrum of early-season diseases including Rhizoctonia, Fusarium and Pythium.

For more information from several major seed companies, check out Syngenta, Pioneer and Monsanto. Also check out a new in-depth report just released by CropLife America called “The Role of Seed Treatment in Modern U.S. Crop Production” and “The Guide to Seed Treatment Stewardship.”

Pythium resistance challenges; new treatment

Pythium caused several thousand corn acres in southeast Iowa to be replanted the past several years. Despite using seed treated for Pythium, they had trouble maintaining a good stand in some fields.

Last year and again this year, corn plants would emerge, but then die, says Alison Robertson, Iowa State University plant pathologist, whose investigative team documented this. In samples brought back to the lab, the mesocotyl tissue was rotten, she says.

Corn growth slows considerably in cold, wet soils with temperatures below 55 degrees, and seedlings become susceptible to Pythium, Robertson says.

“We saw corn at the V2 to V3 stage, that had been sitting in the ground 4 to 5 weeks. All corn seed treatments contain either metalaxyl or mefenoxam, both very effective against Pythium. We don’t know if the seed treatments didn’t last long enough or if the fungicide just wasn’t effective,” she explains.

“Resistance to this fungicide is real, so that’s always a concern. Last year, it appeared the species P. torulosum was a primary problem—80% of the isolates recovered from diseased corn seedlings belonged to this species. But this year we found a wider range of species of Pythium.”

Robertson says she heard of similar Pythium problems last year in Illinois and Indiana, and this year in Nebraska and Minnesota. Ohio researchers reported resistance several years ago. “It seems to be becoming more of an issue,” she says.

Knake says Pythium is in every field, and without a systemic fungicide seed treatment against it, growers would need to delay planting both corn and soybeans, or risk the need to replant too many acres each year.

We still use the original Pythium product introduced in the 1980s, Knake notes. “There’s no confirmed evidence of resistance, but it could develop. For Pythium, there’s only one mode of action. The industry is working on one more, but there’s really nothing a grower can do.”

Robertson and Knake agree that a “next-generation” seed treatment needs to be developed, tested, and made available. Robertson points to ethaboxam, a new fungicide that belongs to a different chemical group than metalaxyl, the primary ingredient that’s been used for years against Pythium and other pathogens.

“It’s a new fungicide that will be combined with metalaxyl and marketed as the AP3 fungicide system. In our 2012 greenhouse evaluations, ethaboxam and metalaxyl in combination reduced root and mesocotyl rot and improved emergence,” Robertson says.

Seeding rate by seed treatment

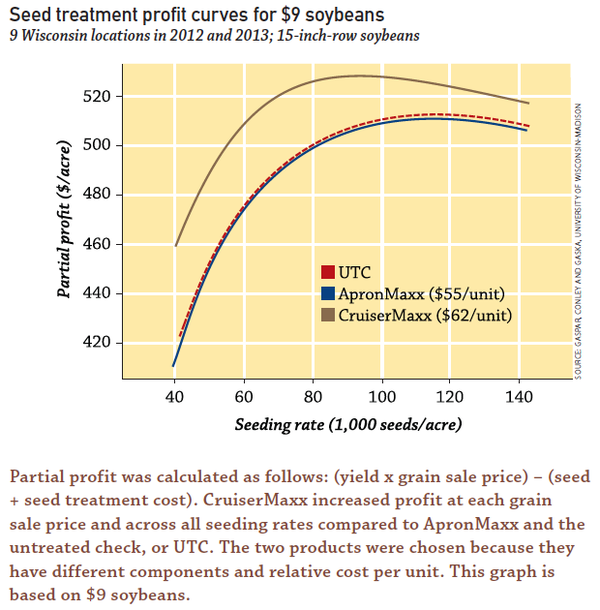

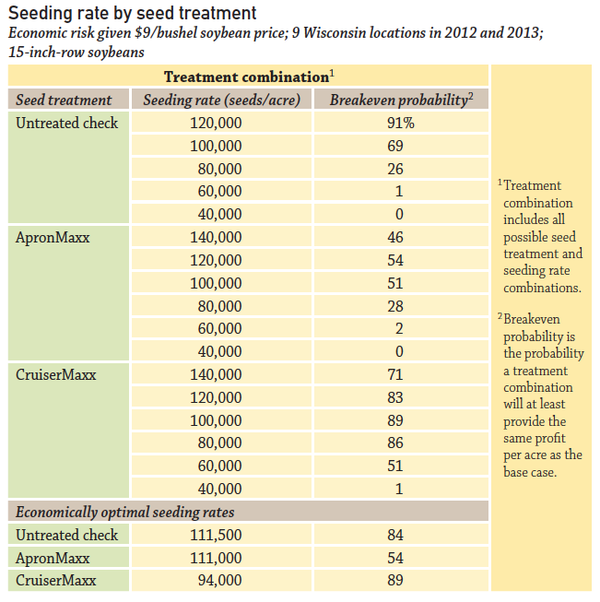

CruiserMaxx at 140,000 seeds per acre had a 71% chance of increasing profit over the base case, and on average for all environments, increased profit by $10 per acre. ApronMaxx and the untreated check obtained breakeven probabilities greater than 50% at rates of 100,000 and 120,000 seeds per acre. However, the average profit increases for all outcomes was minimal (less than $3 per acre). CruiserMaxx produced breakeven probabilities greater than 50% for all seeding rates except at 40,000 seeds per acre, and the average profit increase for all outcomes was more than $17 per acre at a rate between 80,000 and 120,000 seeds per acre. Furthermore, the lowest risk (89%) and largest average profit increase for all outcomes ($20 per acre) with CruiserMaxx was at its economically optimal seeding rate (94,000 seeds per acre).

Source: Both charts taken from research report: “Economic Risk and Profitability of Soybean Seed Treatments at Reduced Seeding Rates,” researched and compiled by Adam P Gaspar, Shawn P Conley and John Gaska, Department of Agronomy and Paul Mitchell, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison. http://bit.ly/1jVpiIR

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like