May 25, 2016

It's easy to "forget" how a law or process got created, but the recent release of the 400-plus page report from the National Academy of Sciences offers some perspective. One key area to look at is the regulatory process for novel crops and food. The report does note that this process varies from country to country, we thought it would be a good idea to offer a refresher on the U.S. system.

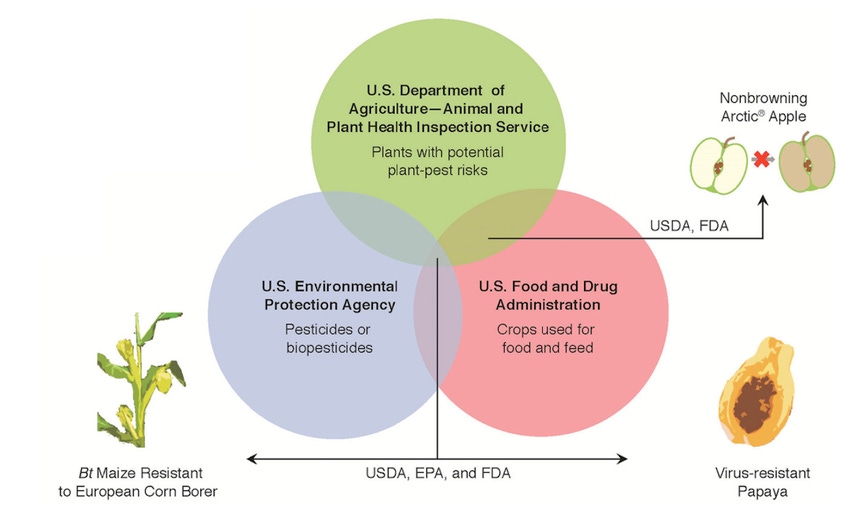

The graphic on this page - from the report - shows how the overlap of three agencies works. If, for example, a new crop were only to be used in ag, never for food, USDA might have sole jurisdiction over its approval. Add in the environment, or the fact that it could be food, and you bring in Environmental Protection Agency and Food and Drug Administration. The overlap of all three agencies impacts some crops, but as the graphic shows since the non-browning Arctic Apple has no pesticidal properties, EPA wasn't involved.

Now for a history lesson: the original regulatory policy for GMO crops was set out in 1986 - 30 years ago - as the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology. According to NAS, this Coordinated Framework "directed U.S. regulatory agencies to use their existing legal authorities to review the safety of products created with genetic engineering in the same manner as similar products produced using conventional breeding."

In essence, how a product is regulated depends on how it will be used, and more than one agency can be involved.

In the food safety world it's the FDA's job to monitor safety, however new whole foods are not required to be approved as safe by FDA before introduction into the U.S. market. Manufacturers are held responsible for food safety and if a problem arises, then the FDA steps in to recall or seize the food. In the past, whole foods developed through conventional breeding - and keep in mind the word "conventional" can include mutating inbreds with cobalt, force crossing plants that are barely relatives and other more ingenious methods - have gone directly to market.

As the report points out FDA has long held that practices used by plant breeders in selecting and developing new varieties have "been proven to be reliable for ensuring food safety." That's why the agency rarely conducts premarket safety reviews.

Digging into the Coordinated Framework

What often is missed in the conversation about regulating GMO crops is the process itself. The report carries an excellent review of the history of the Coordinated Framework noting that the orientation for regulation has always been "in the same manner as similar products made by using conventional breeding."

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy found that current rules could deal with expected products from the new process, and this includes not only biotech crops but biotech healthcare products and other resulting products.

In 1992 the OSTP offered added policy guidance which clarifies a key point that sometimes gets missed in the GMO conversation noting that agencies "shall not regulate products intended for use in the environment (such as crops) on the basis of the process by which they were made,but rather on the 'characteristics of the organism, the target environment, and the type of application.'"

In essence that last guidance divorced the process from the product, which makes sense given the rapid change underway. Regulating the final product that would come to market and not being as concerned about the development or genetic tools used made sense.

There are some exceptions - as with all regulations, the report points out. EPA exempts from the registration process new crop varieties that have been developed to have greater pest resistance through conventional breeding tech, including mutagenesis. The agency claims the distinction on the basis that sexually compatible, conventionally bred plants are less likely to pose novel exposures in the environment.

And USDA has some distinctions in the process, with regulations that apply only to new crop varieties that have been genetically engineered with known plant pest sequences, or using a plant as a transformation vector - the agency doesn't do premarket environmental reviews for crops produced using conventional means.

In essence, regulators have fine-tuned the GMO approval process where necessary. Recently, USDA decided that crops developed using the CRISPR-Cas gene-editing tool - which removes pieces of genetic material rather than adding novel traits to achieve improved plants - doesn't require the same regulatory review as traditional genetically engineered plants. DuPont Pioneer was an early company to get this distinction in the development of future waxy corn hybrids.

When it comes to food - FDA won't label GMO products because it has ruled the food items are substantially the same as those from conventional breeding - corn is corn, soybeans are soybeans. This has been challenged in court, but to date the agency has won and holds strong to no need for labeling the products.

The agency does ask companies to voluntarily provide safety information on new foods produced from novel crops before going to market to demonstrate that the GE food is substantially equivalent and that any added substances are safe. And companies are conducting more internal safety trials checking for allergic reactions and more.

The process can take time, and the length of time for approval has gotten longer in recent years, but as this refresher shows, it's a process that's well-defined and safety focused.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like