Selling your product at a loss is a business model designed to put you out of business. Yet that’s what some academic experts continue to recommend for growers facing another year of low prices.

The idea is to cut losses by taking a low price now, to avoid more substantial flows of red ink if the market never recovers. It’s not a bad trading strategy for those who are in and out of the market for a living. But for farmers growing one crop a year, it’s generally a bad idea.

Futures traders know the benefits of preserving capital. They recognize every trade won’t work. Many will fail, and being stubborn on any one trade can lead to losses that wipe out a grubstake. So they often enter every trade with preset limits of how much they’re willing to risk.

But pricing your product at a loss from the get-go is completely different. There’s no upside to the strategy, only protection against something worse. History and the financial position of most farmers suggest this sort of pain management is just not needed.

Sure, a farmer who can only afford to lose $50 an acre is better off selling now and losing $20, rather than failing to achieve higher prices and going under. But our research shows only 6% of growers are truly financially vulnerable. That is, they’re losing money and have unsustainably high debt.

Times are tough, but not that tough. Using strategies designed for the 1980s farm crisis is looking at a headline proclaiming, “Interest rates rise,” and remembering former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s crushing move to 21%. In reality, it’s unlikely federal funds rates will get back even to 3% in the next three years.

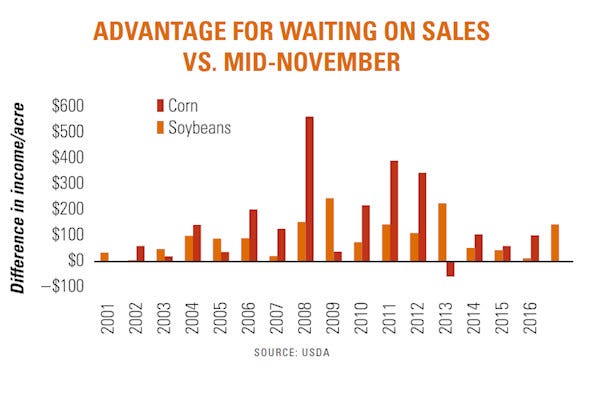

Selling nearly a year before harvest also ignores the volatile history of commodity markets. Even in times of low prices, there can be rallies that take prices to or above the cost of production. To back up that claim, we looked at prices, yields and costs for corn and soybeans going back more than 40 years. The study compared results for pricing crops in mid-November, against waiting for rallies from March 1 to delivery.

Waiting resulted in potential for higher prices in 37 of the 42 years surveyed, or 88%, for both corn and soybeans. The exceptions to the rule demonstrate when selling early may be warranted.

For corn, four of these years came during periods of financial stress, including three in the 1980s. This included 1982, when operating rates topped 17%, as well as 1985 and 1986, the depths of the worst ag recession since the Great Depression. Selling early also produced a slightly smaller loss on corn in 1999, when prices hit their lowest level since the crisis.

The only other year when early sales proved better involved pricing 2013 production in fall 2012. The drought that summer took corn futures to all-time highs. Waiting to sell was also profitable, but not by as much.

The years favoring early sales of soybeans were slightly different: 1975, 1982, 1985 and 1998-99. But soybean rallies after March have taken out the mid-November soybean price every year since then. Soybeans have two shots at a rally most years, due to the importance of the South American growing season, while strong Chinese demand has also surprised the market some years.

Of course, just because a strategy works most years doesn’t ensure success in any given year. And if the U.S. is on the verge of a collapse to very low prices again, selling now may prove best. Lastly, while prices may rally later, the gains mean nothing if you don’t pull the trigger when a profit is offered.

- Decision Time: Risk Management is independently produced by Farm Futures and brought to you through the support of Case IH.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like