August 9, 2016

For decades, scientists have known that there are ways to measure plant health through the use of multispectral photography. The idea that a plant can tell you something in a picture before you can see it with your eyes was borne out with the launch of the first land-focused satellite system — Landsat 1 — back in 1972. The concept is known as remote sensing, and it gained a lot of early attention.

Yet the idea of every farmer turning to remote sensing information for crop decisions didn’t materialize perhaps the same way those early pioneers first envisioned. That’s changing.

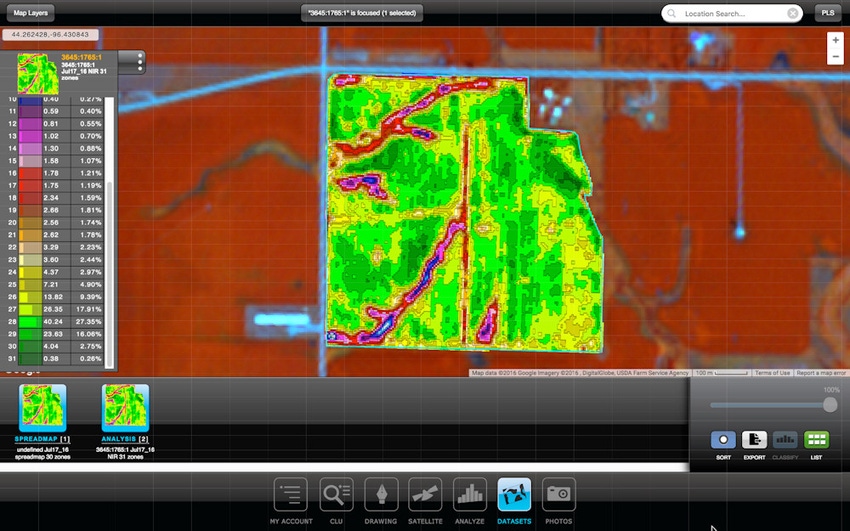

“The industry has woken up,” says Lanny Faleide, president and founder of Satshot, an image-processing firm that has been working with a range of remote sensing information for more than 20 years. “We’ve done actionable variable-rate prescriptions since 1996; however, there is new technology, and the industry has awoken to that.”

He points to the rising use of unmanned aerial vehicles and the fact that “farmers finally understand that images have value.” Add in the ability to automatically store information in the cloud for easier access for analysis and distribution of prescription information, and new tools for in-season remediation of a problem and remote sensing have greater value.

Many levels of data

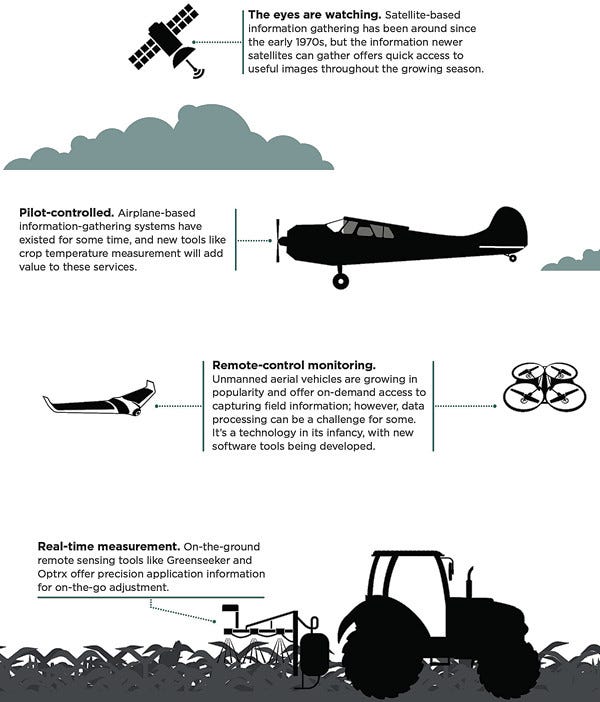

For this review, remote sensing is defined as any system that measures the plant and gathers information without touching the actual plant — everything from ground-based systems like Greenseeker and Optrx to drones to airplanes to satellites.

For Satshot, all those imagery sources can be used to developed usable maps. “We’ll take imagery from any source to process it. A pixel is a pixel is a pixel — it has to be geometrically and radiometrically correct,” Faleide says.

The challenge, however, is taking that information to scale: shooting whole fields or whole farms and having the information available in a timely fashion.

Satshot and its competitor Geosys are capturing imagery from hundreds of miles above the earth. And when you talk about scale, you talk about getting plenty of information in a short time. The challenge

is covering the territory in a timely fashion, and Faleide notes that no system has everything covered yet. However, when it comes to scale, satellites have other image-capturing tech beat. Faleide notes that in a single day satellites are capturing imagery from 100 million acres, and perhaps more.

“You’re shooting imagery at 20,000 miles per hour, and the image swath is 200 miles wide,” he explains. “We’re taking an image swath from Texas to Manitoba that’s 200 miles wide by 1,500 miles long in that pass, and we can have that imagery into our system by tomorrow morning.”

The satellite is the king of efficiently gathering a lot of imagery for analysis. There are some challenges with image capture timing, cloud cover that blocks imagery creation and analysis support — though for that last one Satshots has long been involved there.

Dave Gebhardt, global director of strategic partnerships for Geosys, says his firm, long known for collecting data, is moving to “the other end of the data with the algorithms and the ability to take that data to a higher level of value.”

The aim is to help put the data to work, which means making information available to decision-making software. The company is collaborating with SST Software to add in-season satellite imagery for users in North America and Australia through use of the agX Platform, where users can seamlessly share data. Precision farming applications compliant with the agX Platform can access the Geosys in-season imagery program.

Often when you hear talk of satellite imagery, people bring up its limitations. Yet during the 2015 growing season, Geosys’ Virtual Satellite Constellation delivered an average of more than 15 in-season normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) maps per field across major cropping areas in the United States.

New imagery on tap

A tool closer to earth is the airplane, which can capture more precise imagery over a wide area. However, scale-ability can be a challenge — having pilots that can capture information and move it to the cloud for analysis is important.

Airscout is an Indiana-based company that uses field heat mapping to gauge crop health — a measure the company claims is more precise and sophisticated than infrared or NDVI maps.

The cameras measure the temperature of the crop, which company founder Brian Sutton says is more precise and a better indicator of stress than the more common NDVI images taken today.

“Thermal is not NDVI, which is what the drone and satellite imagery companies are selling,” Sutton says. “NDVI is based on reflected light and has nothing to do with temperature. Our thermal camera completely disregards color and shows actual emitted energy from plants. Because it shows the emitted energy, we can see disease or stress in a plant long before it begins to change color.”

Sutton, an Indiana farmer and licensed pilot, experimented with several NDVI camera technologies before using thermal imaging. He says while NDVI did a good job of amplifying shades of green, the cameras revealed little more than what he could see out the airplane window. “The level of detail and patterns the thermal imaging reveals are well beyond what can be detected with the naked eye,” he says.

Sutton says its thermal image technology is unique. “No one, beyond universities and NASA, is using the same camera and process for aerial field scouting today,” he says. “The processes we use are patent-pending.”

Going with a drone

Even closer to the ground is the drone, which comes in many shapes and sizes. The fixed-wing designs can cover a lot of territory in a single flight, and multi-rotor machines can get solid spot checks and cover smaller field areas. However, that’s changing too as bigger batteries and improved operational software makes multi-rotor machines powerful information gatherers.

“The drone is definitely still in its discovery phase, especially in ag,” says Mike Martinez, marketing director for Trimble Agriculture. “There are some very clear uses for the drone. It is a very young technology, and the development of the tools and how the data gets used is still early in its cycle.”

The key is the Federal Aviation Administration, which is finally putting out rules that will allow non-pilots to use drones in ag (certification is still needed). The challenge is taking the idea of drone information gathering to scale — which means covering a lot of ground so you have the information you need to make decisions.

And image quality can be as much a problem for drones as for satellites; shooting under clouds in gray conditions may not be much better than a blocked image by clouds from a satellite, Faleide points out. That solar contrast provides the light needed to capture the right pixels; clouded sunlight doesn’t provide the same depth of information in the imagery you collect. In fact, wind and light direction can also be an issue. When the drone flies in one direction with the wind at twice the speed it does on the return trip, imagery can be impacted. And there are other factors about lower-level imagery that still need to be worked out.

“We’ve seen service providers use drones as a kind of an advanced high-volume scouting tool, more than doing real prescription mapping,” Martinez notes.

Real-time, in-field

Getting down to earth, on-the-ground remote sensing from the tractor is receiving more attention. Greenseeker, Optrx and others tools from Europe offer real-time adjustment of nutrient applications based on crop information.

Martinez notes that adoption of that technology continues to grow as more producers see its value. And with the advent of tools like the Y-Drop system from 360 Yield Center, which allows for easier in-field action if you detect trouble, the rising use of sensors makes a difference.

Planetary Resources, a company that was working on remote sensing for potential asteroid mining, has teamed with Bayer and will provide imagery and information in the future. The company will use thermal and hyperspectral imagery, which is a next-level remote sensing tool from the sky to capture information beyond near infrared and NDVI.

“Hyperspectral imagery is comparable to an ultra-HD image to a standard high-definition television,” says Chris Lewicki, Planetary Resources CEO. “We’re creating technology that’s good for measuring the composition of crops and thermal imagery.”

He notes the work the company has done on asteroid remote sensing is now being turned earthward to make the same measurements “closer to home.” And he adds that new satellites in Earth’s lower orbit offer improved cost-effectiveness. The company plans to deploy a constellation of 10 satellites in low orbit, with each covering a section of the planet every 90 minutes.

“We’ll have the opportunity to look at any area of the planet twice a day, and with infrared, we can look at night and measure temperature,” Lewicki says.

Bayer is partnering with the idea of adding information to a growing digital farming platform that will evolve over the coming months. “This is a very rapidly evolving marketplace, for sure,” says Stan Martin, data scientist, digital farming, Bayer. “We’ve seen a massive evolution in information management in agriculture in the past 24 months and that continues to evolve.”

Looking ahead

Interestingly, any farmer with a recent model controller for a sprayer, spreader or planter is already able to use the information from the current imaging tools and prescriptions. “Ninety percent of farmers have the technology, and they’re not turning on the switch. It’s all built in,” note Faleide.

And how will this information be used?

Faleide focuses on those variable-rate maps, which he says he can develop with high precision very quickly from a range of image sources from a farm. Crop modeling is getting attention, too.

There are already a growing number of agronomic models used in the market — some to manage inputs like nitrogen, or pesticide application.

“Models have a lot of value as a starting point,” says Gebhardt, with Geosys. “Another way to look at it is this: Every plant in the field is a sensor itself and represents the current status of that crop in that field. Instead of modeling weather, soil, genetics or disease, remote sensing simply asks the plants themselves how they are doing.”

That satellite imagery provides some local measure in the field, and with models built around pests or weather, farmers can make better decisions.

“That’s what we’re helping to guide, working on the return on investment with crop and field monitoring tools that can be licensed from us to provide a deep dive into a field, its variability and infestations that may be in that field,” Gebhardt says.

Enhanced remote sensing imagery from a number of sources will become more important to your farm’s management — whether you gather it right from your sprayer making on-the-go applications, your UAV, a scouting airplane or a satellite. The ability to put that information to better, and more timely, use in agriculture will make a difference.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like