Take a book from a set of 1970 Britannica encyclopedias. Run the pages through a paper shredder a couple times, then turn the pieces sideways and run them through again, until all you have left is a pile of confetti. Then sit down with some friends and reassemble the pieces. You won’t have time to celebrate your accomplishment long, however, because you’re only halfway through. You need to grab another book, say from a 1990 set of Britannica encyclopedias, and repeat the process.

According to USDA/Agricultural Research Service scientist Brian Scheffler, head of the ARS Genomics and Bioinformatics Research Unit, in Stoneville, Miss., this is what it was like for scientists to sequence the peanut genome, a task recently completed by the International Peanut Genome Initiative, a multinational group of crop geneticists which has worked in cooperation for the last several years.

Scheffler, scientists from University of Georgia, University of California – Davis and partners in nine countries participated in the project.

The new peanut genome sequence will be available to researchers and plant breeders across the globe to help breed more productive, more resilient peanut varieties. The sequences provide researchers access to 96 percent of all peanut genes in their genomic context, providing the molecular map needed to more quickly breed drought-resistant, disease-resistant, lower-input and higher-yielding peanut varieties.

Peanut's two parents

To accomplish the task, scientists sequenced the two parents, Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis, of today’s commercial peanut. The two wild species were collected from nature decades ago. One of the ancestral species, A. duranensis, is widespread, but the other A. imaensis, has only been collected from one location and may now be extinct in the wild.

Today’s commercial peanut, Arachis hypogaea, is the result of a natural cross that occurred between the two species in northern Argentina between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago. This makes the commercial peanut a tetraploid, meaning it carries two separate genomes, or sub-genomes. (Most commercial cotton varieties are also tetraploids, but the cross between its wild parents occurred millions of years ago).

So why didn’t scientists sequence today’s commercial peanut instead of the two wild parents?

Referring back to Scheffler’s encyclopedia analogy, this would be like shredding both of the aforementioned encyclopedias at once into one giant pile of “confetti” then restoring each to its original condition. From that mess, “You wouldn’t know which piece went to which book. So we had to first sequence Parent 1 and Parent 2, and then take a look at cultivated peanuts,” Scheffler said. “We had to take a step back before we could go forward.”

Knowing the genome sequences of the two parent species will allow researchers to recognize the cultivated peanut’s genomic structure by differentiating between the two sub-genomes present in the commercial peanut. Being able to see the two separate structural elements will also aid future marker development – the determination of links between a gene’s presence and a physical characteristic of the plant. Understanding the structure of the peanut’s genome will lay the groundwork for new varieties with traits like added disease resistance and drought tolerance.

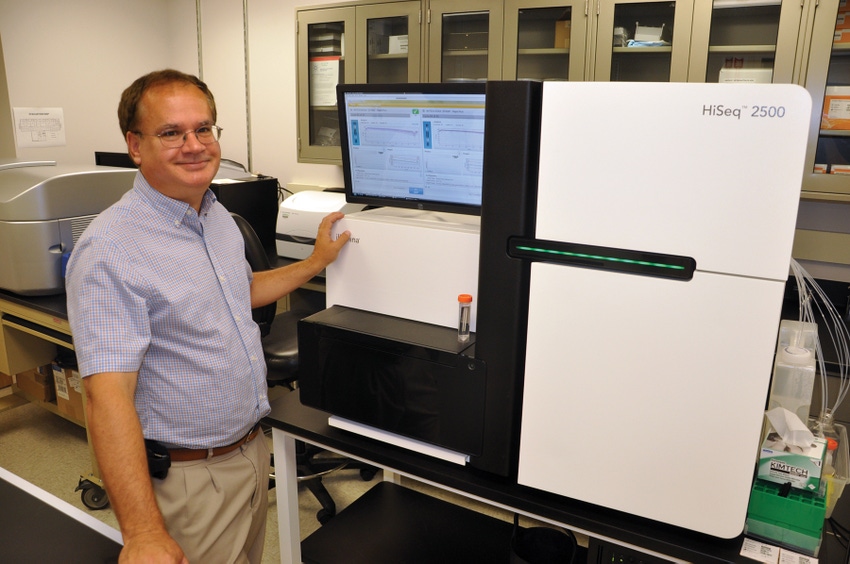

Handling huge amounts of data

Scheffler said the international project “was a very complicated process. The peanut is big, about 2.4 billion base pairs, but only a small portion actually contains the DNA that codes for the genes.”

The human genome has about 3 billion base pairs and cotton about, 2.4 billion.

The handling and analysis of the massive amounts of information from genomics research is a science itself, called bioinformatics.

Each highly-advanced sequencing machine can generate as much 6 terabytes to 8 terabytes of data. (one terabyte equals 1,024 gigabytes).

“So you need some ‘oomph’ to handle that. Our biggest computer has about 1.2 terabytes of RAM (random access memory),” Scheffler said. “Your computer at home probably has a couple of gigabytes of RAM.”

Each participant was assigned a specific part of the genome initiative. Scheffler’s lab worked with scientists in Tifton, Ga., “to determine which genes were turned off or on, or how much they were turned off or on, based on the tissue of the plant,” said Scheffler, who is on the advisory board for the genome project. “Our major effort now is continuing to flesh out and improve some of the gene information. The problem is when we put the ‘encyclopedias’ back together, we didn’t do it perfectly. But it’s never perfect. You still have pieces to figure where they fit.”

Scheffler says there is still sufficient data to put the sequenced genome in the hands of breeders in a usable, friendly format.

“It could save years in developing a cultivar,” Scheffler said. “For example, if the DNA marker is very accurate in predicting disease resistance, then everything the breeder puts into the field can have that disease resistance. He doesn’t have to screen for it every year.”

Plant geneticists David and Soraya Bertioli of Brazil, who also participated in the project, said, “Until now, we’ve bred peanuts relatively blindly compared to other crops. These new advances are allowing us to understand breeding in ways that could only be dreamt of before.”

The initiative brought together scientists from the United States, China, Brazil and Israel. The U.S. Peanut industry collaborated to provide $6 million in funding spread over five years. The groups that are funding $2 million each are the National Peanut Board, on behalf of farmers; the American Peanut Shellers Association, on behalf of shellers; and a large collection of manufacturers, which included the substantial contribution by M&M Mars.

Cultivated peanut has a total global production area of 59 million acres. Americans consume more than six pounds of peanuts per capita annually. U.S. peanut production, valued at $2 billion annually, extends from southern Virginia to Florida and westward to New Mexico.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like