“Mississippi’s here to stay as part of an U.S. peanut industry that’s here to stay," says Marshall Lamb, director of the USDA/ARS National Peanut Laboratory at Dawson, Ga. "The state’s yield has been steady increasing, from an average a few years back in the 2,800 to 2,900 lb. range to 4,400 lbs. last year.” Mississippi led the nation in average yield in 2011, but was edged out in 2012 by Georgia’s 4,550 lb. yield.

“Mississippi has the water, soils, and high caliber growers to produce some of the highest quality peanuts in the U.S. year-in, year-out, and to be a very big player in the peanut industry,” says Marshall Lamb, director of the USDA/Agricultural Research Service National Peanut Research Laboratory at Dawson, Ga.

‘It has been rewarding to watch the peanut industry in Mississippi grow,” he said at the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation’s summer peanut commodity meeting at Hattiesburg.

“Mississippi’s here to stay as part of an industry that’s here to stay. The state’s yield has been steady increasing, from an average a few years back in the 2,800 to 2,900 lb. range to 4,400 lbs. last year.”

Mississippi led the nation in average yield in 2011, but was edged out in 2012 by Georgia’s 4,550 lb. yield.

“As west Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma go through the trials of depletion of the Ogalalla aquifer and continued drought, the industry needs new acres and new partners to grow the demand for peanuts. We’re glad to see Mississippi investing in that growth.”

“Although acreage may be down this year in Mississippi and across the peanut belt, we can look for acres to go back up next year.”

Aside from adverse weather that prevented some intended acres from being planted this spring, Lamb says, the chief reason for the big drop in acreage — Mississippi plantings are estimated to be down about half from 2012’s 48,000 acres — was last year’s record crop and huge carryover that put a damper on the market and sent contract offers for 2013 into a nosedive.

Peanut markets have been on “a wild, wild ride” since government quotas were eliminated, he says, going from years of over-production to years of little more than pipeline supplies, and resulting in wide swings in contract prices offered to growers.

In recent years, both the 2010 and 2011 crops “were rough in terms of quality, and going into 2012 we had some very good offers for farmer stock contracts, which resulted in acreage being increased to 1.6 million. A lot of that crop is still hanging over us — not so much because of the acreage response, but because of the yield that averaged 4,192 pounds across that acreage.

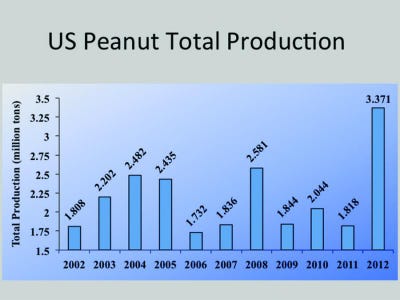

“I would never have believed the U.S. could have that kind of yield; it was absolutely amazing. In 2008 and 2011, we hit what everyone considered a new summit in yield, but 2012 topped even that — over 2 tons per acre of extremely high quality peanuts, with very few milling losses. We delivered nearly a 3.4 million ton U.S. crop.

“We didn’t necessarily overplant, at 1.6 million acres. We just didn’t count on that record yield, which led to about 1.2-1.3 million farmer stock tons (FST) of carryout at the end of the marketing year.

Carryout is key number

“In terms of supply and demand, carryout is the number we worry about each crop year. It represents the amount of peanuts in the pipeline August/September/October — the three-month period before new crop deliveries become available to processors.

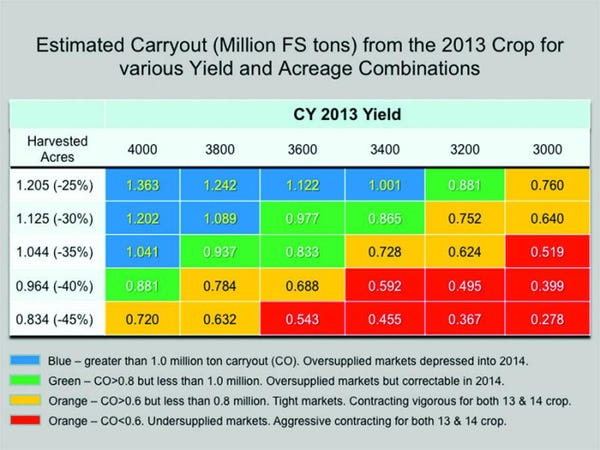

THE IMPACT of various combinations of acreage and yield on peanut carryout is shown here.

“U.S. shelling capacity is about 165,000 FST per month, or about 500,000 FST for the three-month period. If we continually hit a carryforward of 400,000 to 500,000 FST, there might be supply interruptions from shellers to manufacturers, and we don’t want to see that, because it will slow demand.

“I don’t like to see a carryout of 800,000 to 900,000 FST, because too many peanuts suppress the price signals that come from the manufacturers to the shellers to the farmers. I like to see a little buffer, with a carryout of about 600,000 FST. Below that, manufacturers and shellers get nervous.”

For example, he says, in 2007 the carryout was only 510,000 FST, which resulted in early contract offers for 2008. “Farmers planted more, we had a good yield, and produced 2.5 million tons. That resulted in a carryout of over 1 million FST, which totally flattened the market. In one year, we’d doubled the carryout, and the market responded accordingly. In 2009, we planted fewer acres and produced 1.8 million FST, but still ended the year with 920,000 FST of carryout. It’s hard to get that big an elephant off your back.”

But in 2011, with a drought-decimated crop in Texas, production of 1.8 million FST and increased demand, carryover dropped to an extremely low 380,000 FST

“That kind of number makes manufacturers and shellers sweat,” Lamb says. “Manufacturers fear supply interruptions and shellers fear they won’t be able to deliver the peanuts they’ve forward contracted. That number is the reason that at the end of harvest in 2011, growers who had uncontracted peanuts could get anywhere from $1,000 to $1,100 per ton, where normally they’d be trading for $450 to $550.”

But he says, where the low carryover had the biggest impact was on price signals for the 2012 crop. “In the winter of 2011 and spring of 2012, growers were being offered contracts of $700 to $750 per FST in order to try and take acres away from corn and cotton into peanuts.”

The result: 1.6 million acres of peanuts, a record yield, a 3.4 million FST 2012 crop, a record carryover, and a price-depressing outlook for growers in 2013.

China purchases a help

An unexpected bit of salvation, Lamb says, was that problems with India’s crop resulted in China coming into the market and buying U.S. peanuts.

THE MUCH ABOVE AVERAGE peanut yield for the U.S. in 2012 is graphically illustrated here.

“India is a large supplier of peanuts to China, and when China came into the market they came like a raging bull. This helped to reduce our large stockpile of peanuts. But when China stopped buying, they stopped cold. I’m told they are now showing some renewed interest, and we certainly hope they will begin buying again.

“Exports have helped reduce the big oversupply from 2012, and I don’t think we’ve accounted for all the export numbers yet because of the lag in reporting.”

While manufacturers “would be happy for carryout to stay at 800,000 to 900,000 FST, which would keep contract prices to farmers at $450 to $475 per FST,” Lamb says, “the big question now is how much production is needed in 2013” to get the U.S. to the optimum-for-growers 600,000 FST carryout?

“To get back to a reasonable carryout, we need about 1.5 million FST of production, or 3,400 pounds per acre on 980,000 acres. But it has been a long time since we’ve had that few acres. That would be a 40 percent decrease from 2012 and about 30 percent from the 2008-12 average.

“USDA is currently forecasting an average yield of 3,800 lbs. I can’t for the life of me see that happening; except for 2012, we’ve never produced that many peanuts. I prefer to use 3,400 lbs.”

In the weeks ahead, Lamb says, growers need to be aware of forfeiture dates for peanuts in the government loan.

“When peanuts are put in the loan, the grower has 9 months to market that crop. The loan is non-recourse — you can forfeit the peanuts and walk away, and the government will assume the responsibility of getting them sold. But, there currently are offers for loan peanuts, and farmers should not let a loan expire if they have an offer.”

He says 11,000 tons of peanuts in the loan expired in June; 300,000-plus tons will expire in July. “The big bad boy on the block is August, when 640,000 tons will come up for forfeiture, if not sold. I hope all will get sold.” In September, about 250,000 tons will expire, and October just under 200,000.

“In the last couple of weeks, shellers have been trying to buy loan peanuts,” Lamb says. “I don’t think we really want to see a lot of peanuts forfeited. The peanut program is working, and if a lot of peanuts are forfeited, it will result in increased costs to the government — and I think that’s something we need to stay away from.

“Farmers who have peanuts in the loan need to keep an eye on expiration dates and try to avoid forfeiture if offers are available. There’s no need to forfeit peanuts if there’s an offer on the table.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like