They are tiny and they do not play well together. For Mark Hoddle that is a good thing.

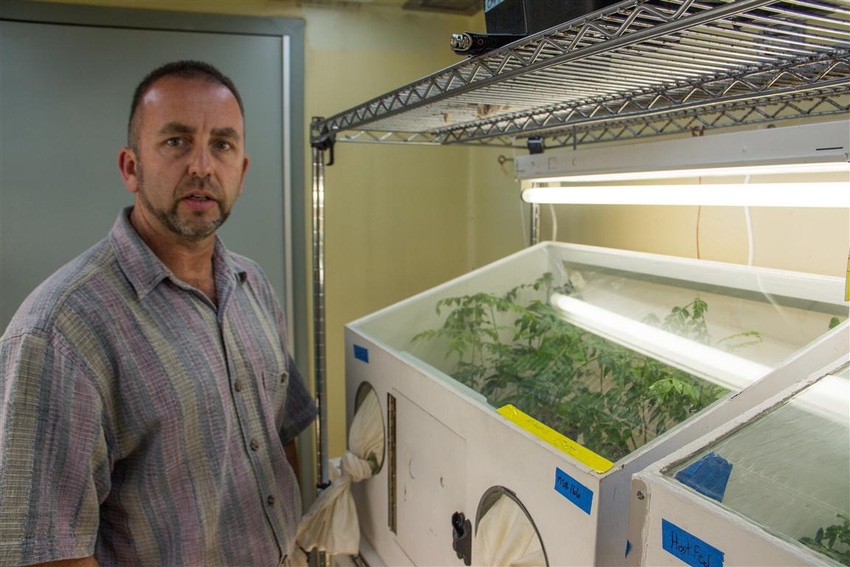

Hoddle is an entomologist with the University of California, Riverside (UCR). He has been working on biological control measures for the Asian citrus psyllid for more than two years now and has discovered two different parasitic wasps that show promise in helping control populations of the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP).

One of the parasites, a miniscule wasp called Tamarixia radiate (Eulophidae) is smaller than its ACP prey, which is very small itself. Nevertheless, the wasp is quite effective at killing the ACP, provided there aren’t any Argentine Ants around to protect the ACP. More on the ant later.

Hoddle began releasing the tiny wasp on citrus trees and plants in southern California in 2011. While releases continue under the direction of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, Hoddle said early indications suggested that the Tamarixia wasp appeared to do well on its own from the very beginning.

“What was remarkable was we had put out few parasites in relatively few areas (and) they survived just fine,” Hoddle said. “They came through their first winter here in southern California with no problem. That is always the first test: can they survive their first winter?”

Like the ACP, which is native to Asia and has spread throughout much of the citrus-growing regions of the world, Tamarixia radiate is not native to North America. Hoddle found the parasitic wasp in Pakistan and was able to collect it after a computer search for climate similarities to southern California and a bit of pure happenstance.

Serendipitous introduction

Through his university contacts Hoddle was introduced to Iqrar Khan, a UCR alum who is the vice chancellor of the University of Agriculture in Faisalabad, Pakistan, and a world authority on Huanglongbing (HLB) and other citrus diseases. Khan earned his masters and doctoral degrees from UCR. Hoddle said it was a “pure fluke” that he met Khan and subsequently learned of the Tamarixia in Pakistan.

“He has been a very enthusiastic supporter of this project because it helps his university and it ties his university back to UC Riverside,” Hoddle said.

Through this introduction Hoddle and his wife, Christina, also an entomologist at UCR, were able to travel to Pakistan to collect the Tamarixia and bring them back to the United States. That in itself was quite a feat.

“This is a very complicated process to get permits to bring back boxes of parasites,” Hoddle said. “We are flying from Pakistan to the United States, carrying a box with a big label on it that reads: ‘under no conditions can this box be opened.’ Naturally the security people are very worried about this box that they can’t open or X-ray.”

In spite of some delays at various airports, Hoddle said their paperwork to import the invasive pests was in order and they were ultimately allowed to continue with their box of wasps, which remained closed until they returned to his UC Riverside quarantine lab.

While the Tamarixia has a rather large range, stretching from the Middle East through Indonesia and Asia, the Punjab region of Pakistan was chosen because of its relatively close climatic match to southern California.

“Before we started this program there were no parasites attacking the Asian citrus psyllid here in California,” Hoddle said.

Matching climates

A climate match of 70 percent between the two regions was enough for Hoddle. He collected Tamarixia from a number of locations, figuring that the biological diversity of insects collected would diversify the samples and allow reproducing populations to adapt over time to the southern California region.

Not only would wasps be released in Los Angeles and the Inland Empire, where conditions range from coastal to hotter and drier in Riverside and San Bernardino counties, but they would have to survive the extreme heat of Imperial County, where summertime temperatures can exceed 120 degrees.

To date more than 160,000 parasitic wasps have been released in over 400 locations spanning 350 zip codes, 64 cities and six counties in southern California. Those counties are: Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside, San Diego and Imperial.

Hoddle is encouraged by the success of the program, and moreover, by the biological success of the wasp. Since it was first released, it has developed its own breeding populations and has been discovered as far as eight miles away from initial release sites, indicating that it is quite mobile.

What makes the Tamarixia attractive to entomologists is its exclusive diet of ACP. Another benefit of the Tamarixia is it reproduces more females than males. The females tend to live 12-24 days and will produce between 166 and 300 eggs over their lifetime.

The Tamarixia wasp attacks the third, fourth and fifth instars, or development stages, of the ACP nymph. Earlier nymph stages become feeding grounds for female Tamarixia as they literally suck the blood from developing nymphs, killing them immediately.

This host feeding technique is quite common with the Tamarixia, as females feed to provide protein and other nutrients for the eggs they will eventually lay under the developing ACP nymphs that they have not previously parasitized.

Hoddle said he and his technicians in the quarantine lab at UCR have witnessed female Tamarixia attack adult psyllids, stinging them to death.

“It’s not very common, but I’ve seen it and my technicians have seen it in the quarantine cages a few times,” he said.

Hoddle stresses that the psyllids contained in his quarantine lab have all tested negative for HLB. That was one of the conditions established prior to setting up this lab, he said.

What makes the psyllid so deadly to citrus, according to Hoddle, is in how they feed. He likes to call the ACP “flying syringes.”

Psyllids are obligate phloem feeders, meaning they are genetically required to feed on the phloem in citrus trees and plants in order to survive. They do this through a needle-like feeding tube. Their bodies act as a syringe, drawing phloem into them. If the HLB bacteria are present in the tree they are feeding upon, they can then transport that bacteria to another tree, where it can be transmitted through the feeding process.

This is in large part the reason for California’s “search-and-destroy” attitude towards finding trees with HLB. While only one tree has been discovered in the state thus far, officials fear there are many more that have yet to display clear symptoms of HLB. This is why controlling the spread of the ACP, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley where small numbers have been discovered, is so critical for the citrus industry.

No 'silver bullet' solution

Hoddle cautions that the Tamarixia, and another parasitoid called Diaphorencyrtus aligarhensis (Encyrtidae), are not “silver bullets” in the ACP/HLB fight. Nevertheless, they do offer hope. The Diaphorencyrtus aligarhensis could be released later this year as Hoddle awaits U.S. Department of Agriculture approval to release the parasite. While the Diaphorencyrtus aligarhensis works a little differently than the Tamarixia radiate, it nevertheless is another tool in the box of biological control measures officials can use in controlling the ACP.

Commercial orchards will continue to spray for the ACP, but urban environments such as Los Angeles will employ biological control measures because the spray program operated by the state is simply too expensive for the state to continue.

“As long as we maintain well-irrigated urban environments with plenty of citrus in them the Asian citrus psyllid is going to be here to stay,” he said.

That is why these biological control measures remain just that – control measures. Hoddle said he will consider the biological control program successful if it can show a 30 percent kill rate of ACP by the parasitic wasps.

Important in this battle will be control of the Argentine Ant, which is quite protective of the ACP because of the sugary honeydew it secretes as a byproduct of phloem feeding.

According to Hoddle, about 90 percent of southern California is infested by the Argentine Ant, which is also a non-native, invasive pest. In studies across southern California, Hoddle discovered that about 55 percent of ACP colonies are guarded by the ant because it provides an easy food source in the honeydew. In those areas the Tamarixia is only effective in killing about 12 percent of the psyllid population. However, in areas with no ant activity, parasitism jumps to over 91 percent, Hoddle said.

“That’s why I’ve been suggesting to the Citrus Research Board and anybody else who’s been trying to do something with bio control with the ACP that if you want to get the Tamarixia established in an area you might have to go in and pre-treat an area to get rid of the ants,” he said. “You’re just working against yourself if you’re putting out thousands of parasites and the ants are just going to eat them.”

An online video published by the Center for Invasive Species Research (CISR) shows Tamarixia being released in southern California. Hoddle is the CISR director.

More stories in Western Farm Press:

EPA crafts new Clean Water Act rule

Growers see cost of business continuing to increase

Tree nut farm advisor brings much to Fresno, Madera counties

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like