The "Christmas rush" had a new meaning late last week as a major snowstorm was predicted to dump six inches or more snow on the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. Combines were out in force trying to get as much corn and soybeans out of the field before the storm.

Continuing wet weather has delayed corn harvest across much of the country. As of early December, for instance, 10% of Maryland's corn crop was still standing in the field. More than 15% of Pennsylvania's corn remained in the fields at that point.

That's a perfect scenario for developing ear corn molds. The white and pinkish colored fusarium molds open the risk of mycotoxins. Many Pennsylvania farmers were seeing mold symptoms on corn a month ago, according to Greg Roth, Penn State Extension corn agronomist. Not every mold carries the mycotoxin risk, though.

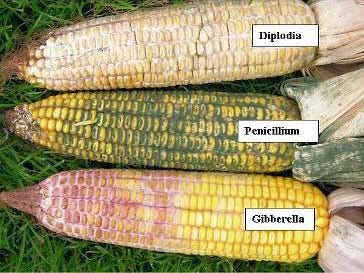

Alternaria, a common black sooty mold is in wet corn crops has no potential for mycotoxins. Neither does the white fuzzy diplodia ear mold. But white or pink colored fusarium molds do.

Let corn stand into winter?

That depends on how much more corn yield you want to lose, suggests Roth. Losses are probably greatest where there's potential for wildlife damage and lodging issues.

Most often, it pays to bite the bullet and harvest the crop. To estimate the tradeoff between potential losses and drying costs, check out the University of Wisconsin's new Excel Field Loss Calculator for Field Drying Corn.

Also consider selling wet corn, possibly to livestock producers with high-moisture grain storage. Be sure to consider the actual net value of wet grain income before deciding on a marketing option since moisture discount schedules vary considerably.

Although, the Gibberella fungus can produce a white-colored mold which makes it difficult to tell apart from Fusarium, the two can be distinguished easily when Gibberella produces its characteristic red or pink color mold.

Gibberella zeae and Fusarium graminearum produce two mycotoxins – vomitoxin or DON) and zearalenone. Both have detrimental effects on swine and other livestock.

ONE IS DANGEROUS: The white moldy ear has Diplodia. The green middle ear is Penicillium. The bottom red/pink mold is characteristic of Gibberella ear rot, which can produce mycotoxins.

Feed containing low levels of vomitoxin (1ppm) can result in poor weight gain and feed refusal in swine. Zealalenone is an estrogen and cause reproductive problems such as infertility and abortion in livestock, especially swine.

Unlike Gibberella, Fusarium infected kernels are often scattered around the cob amongst healthy looking kernels or on kernels that have been damaged for example by corn borer or bird feeding. Fusarium infection produces a white to pink or salmon-coloured mold. A "white streaking" or "star-bursting" can be seen on the infected kernel surface.

Test before feeding moldy grain

Here are a few tips, courtesy of Iowa State Cooperative Extension.

Test for mycotoxins before feeding moldy grain, or if possible before putting it in storage. The best sampling method is to take a composite sample of at least 10 pounds from a moving grain stream, or to take multiple probes in a grain cart or truck for a composite 10-pound sample.

If toxins are present, it is possible that the grain might be fed to a less sensitive livestock, such as beef cattle, depending on the specific toxin and its concentration. A veterinarian or extension specialist can help with these decisions.

Cleaning the grain removes fine particles that are usually the moldiest and most susceptible to further mold development. Good storage conditions (proper temperature and moisture content, aeration, insect control, and clean bins) plus regular inspection are essential.

For additional information on sampling and other aspects of ear rots and mycotoxins, see Iowa State University Extension publications PM 1800, Aflatoxins in Corn (free).

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like