Last week while I was at the cattlemen's meeting in Nashville, I happened across Kansas economist Glynn Tonsor in a hallway and asked his opinion of the latest cattle inventory report. I got something better.

He pretty much brushed off the report as unsurprising, but then he told me about a study he and fellow economist James Mitchell just authored on structural changes in the national cow herd and the effects on the cattle cycle.

We all know the last cattle cycle was a strange one because of drought-induced sell-offs across major portions of cattle country. Nonetheless, there are some interesting trends which are shrinking the size of the cow-population swings, if not the length of the cycle.

To make the long story short, bigger calves and the bigger cows that produce them create more tonnage of beef and meet demand with fewer cows in the national herd.

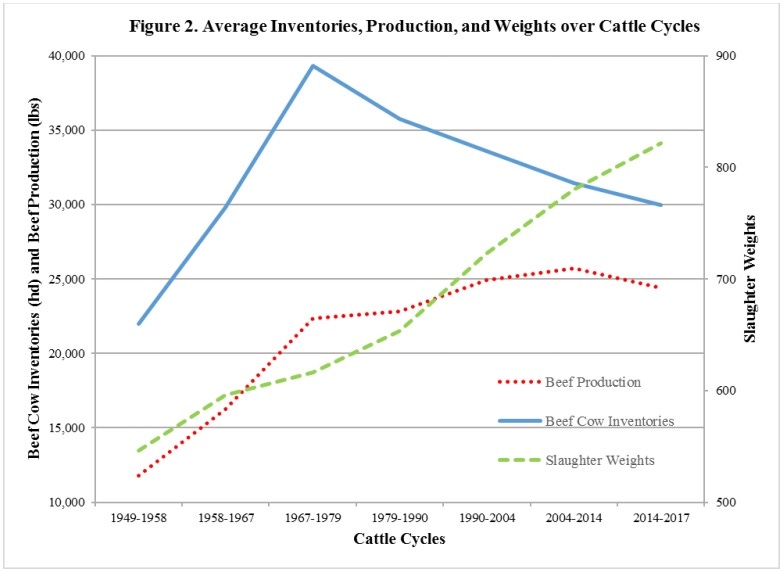

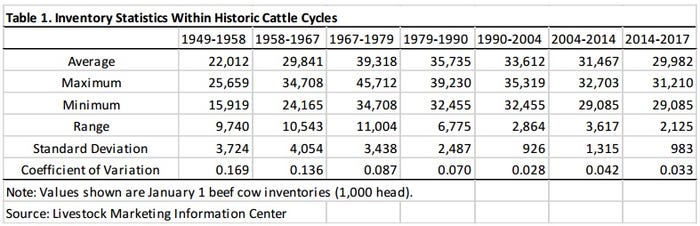

In looking at these charts, look at the narrowing of the cycle obvious in the tonnage of beef production from each cycle, and at the number labeled the coefficient of variation (COV). Tonsor and Mitchell explain the COV is an alternate measure which "assesses inventory variations in a context relative to base inventories within each cycle."

Table 1 shows COVs have declined consecutively over all cycles going back to 1949. Combined, the COV and range statistics indicate the changes in inventories within cattle cycles have become steadily smaller through that timeframe.

This chart shows how fewer cows appear in each cattle cycle.

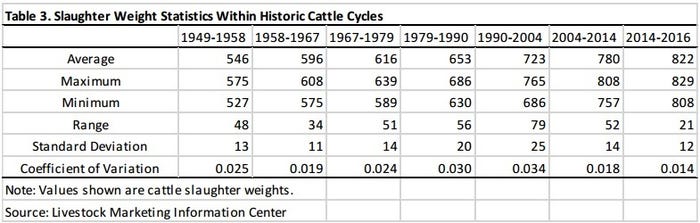

Table 3 shows the large and steady increase in slaughter weights and an actual decrease in the COV of weights within each cycle.

This chart shows how slaughter weights have increased in each cattle cycle, and how they have actually decreased in variation, as well.

The two trends are put into the graph at the lead of this story, showing a sharp drop in the number of cows, a sharp increase in slaughter weights, and an increase in beef production until 2004, then a slight decline

Tonsor and Mitchell wrote, "This effectively reduces demand for beef cows, relative to the past where less beef was produced per animal moving through the industry's supply chain."

So, what will be the future effect of these trends?

If cows remain relatively the same size as they are now, and if beef consumption overall keeps shrinking, this suggests further downsizing of the national cow herd. Perhaps it also suggests slightly shorter cattle cycles, if demand is satiated more quickly with fewer cows. The classic cycle length was once said to be 10 years, and Tonsor's paper suggests nine to 13 years as the typically accepted range.

Any number of variables, such as significant downsizing of average cow size or an increase in demand because of higher consumer disposable income, could alter the relationships and change the trends.

You can read the full report on Kansas State University's Ag Manager website.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like