Coming into 2020, forecasters were expecting higher hog prices and higher pork production.

Then COVID-19 happened.

The virus has sickened and killed people, caused packing plants to cease or reduce operations and emptied store shelves as people have sheltered at home and dramatically reduced or eliminated out-of-home dining.

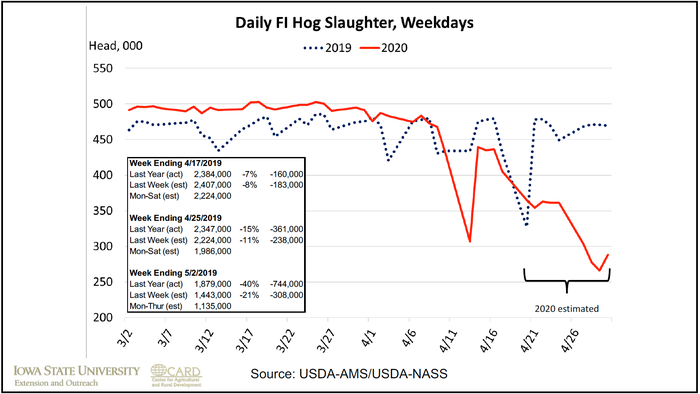

Daily hog slaughter had been running at above year ago levels through early April, said Lee Schulz, associate professor in the Iowa State University Economics Department, during a FarmDoc Daily webinar. There was a decrease in slaughter during the Easter holiday, but slaughter resumed to near year ago levels for a few days before beginning a downward trajectory after April 16. When compared year-to-year through April 30, federally inspected hog slaughter is down 40%, Schulz said. Compared to a week ago, hog slaughter is down 21%.

It's not unusual for plants to go offline for a time for maintenance or because of an event like a fire, but it's usually isolated and there's a known path to recovery. With COVID-19, the path to recovery is unknown as it's a workforce issue.

Before COVID-19 disrupted the nation's economy, unemployment was historically low. The nation's unemployment rate was 3.5%. Looked at another way, there was .8 unemployed persons for every job opening. Wage rates have been increasing in the production sector to attract workers, but the industry hasn't been able to create enough workers for the needed production levels, Schulz said.

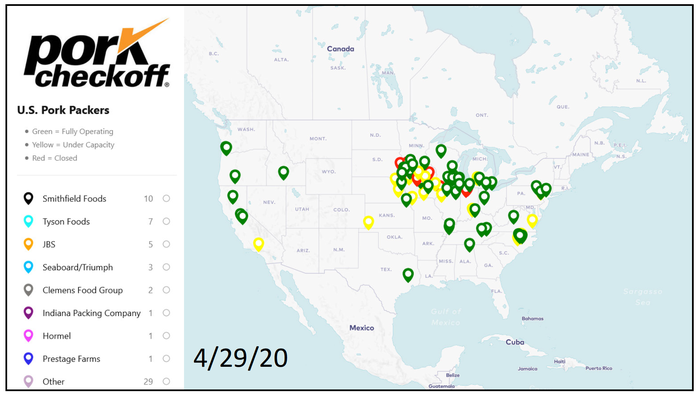

A Pork Checkoff graphic shows the distribution of pork processing plants in the U.S., with many located in the Midwest. In Iowa, for example, three of every 1,000 jobs are in the meat-packing sector. In the Sioux City, Iowa, area, which includes parts of Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota, 15 of every 1,000 jobs are in the slaughter and meat-packing sector.

With 500 workers testing positive from the JBS plant in Worthington and the nearby Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls shuttered because of a COVID-19 outbreak there, it's unknown when plants will resume normal capacity.

House Agriculture Committee Chairman Collin Peterson held a press conference at the JBS plant to announce the creation of a task force to get the plant operating again a day after President Trump signed an executive order mandating the plants keep operating.

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, who joined Peterson at the conference, said it's not so simple.

"No executive order I do or the president does is going to change the fact that the virus will infect you if you don't do things right and no executive order is going to get those hogs processed if the people who know how to do that are sick," he said.

With workers out sick, producers don't have a place for their market hogs, which is creating a backlog. Some producers are killing hogs. JBS has a skeleton crew on staff to kill hogs and truck the carcasses out for disposal. Peterson said they needed more trucks to haul away the carcasses.

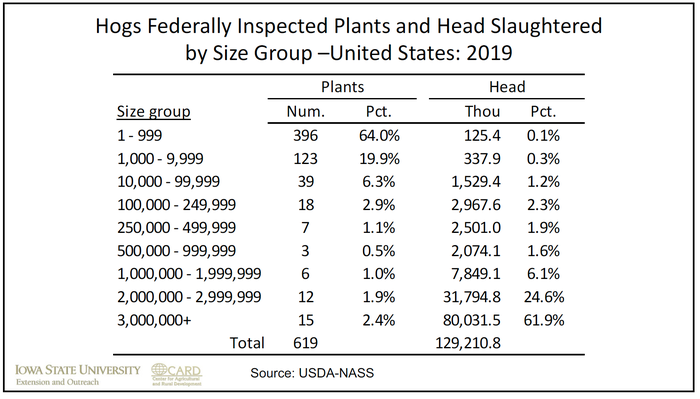

In the U.S., 15 plants slaughter 62% of the nation's hogs, according to USDA NASS data, Schulz said. Those 15 plants slaughter over 3 million hogs per year. When these plants close, there is no simple solution to work through the backlog of hogs. The smaller processors don't have the capacity to make up for the loss of the large packers.

Read more about:

Covid 19About the Author(s)

You May Also Like