If you’re anything like me, you spent the past few days icing your neck after the whiplash from the March 31 USDA reports.

Trade estimates largely missed the mark on Wednesday’s USDA 2021 Prospective Plantings report. Lower acreage estimates for 2021 corn and soybean production sent futures contracts soaring up to each commodity’s respective daily limits - $0.25/bushel for corn and $0.70/bushel for soybeans on Wednesday, before easing slightly in Friday’s trading session.

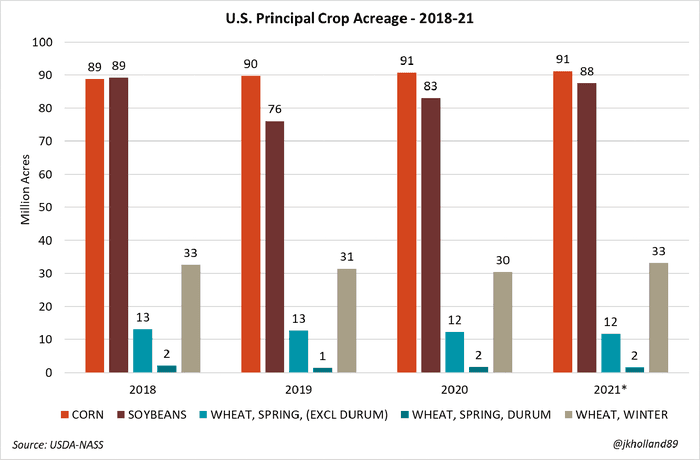

USDA expects farmers will plant 91.1 million acres of corn, 87.6 million acres of soybeans, and 46.4 million acres of wheat. Of that total, USDA expects an 8.8% increase in winter wheat acreage with 2021 sowings at 33.1 million acres while spring wheat acreage will fall 4.2% from 2020 at the hands of higher corn and soybean profits to 11.7 million acres. That’s a principal crop acreage increase of 2% from 2020.

While the news favors farmers, it is somewhat concerning for the corn and soybean industries as a whole. Given a trendline yield of 179.5 bushels per acre for corn, 2021 U.S. corn production will be just a hair higher than 15.0 billion bushels. It would be the second largest crop on record, after 2016’s haul of 15.1 billion bushels.

And will it be enough to meet demand? Preliminary USDA forecasts peg total 2021 corn usage at 15.1 billion bushels – and that’s using a very conservative export estimate. At the current projections, ending corn stocks will likely shrink to 1.4 billion bushels. That results in a stocks-to-use ratio of 9.3%, or a carryout of 34 days. It will be the tightest carryover for the corn industry since 2013.

Record-tight soybean supplies

But what is more concerning is the projected soybean acreage estimate for 2021. It was no secret that 2021 soybean acres are locked in a fierce battle against other profitable commodities, namely corn, sorghum, and canola. But on the heels of an already tight 2020/21 ending supply, markets estimated that a minimum of 90 million acres of soybeans would be necessary to alleviate the ongoing supply crunch.

And that didn’t happen on Wednesday. USDA’s estimate of 87.6 million acres of soybean acreage expected to be planted this spring would translate to 4.4 billion bushels of production, if a trendline yield of 50.8 bushels per acre is realized.

While that value would be the third largest soybean crop in U.S. history, it would only raise 2021/22 beginning stocks to approximately 4.56 billion bushels. Early USDA forecasts predict new crop soybean usage will top 4.53 billion bushels – and that’s not factoring in a potential uptick in exports if the Brazilian crop comes up short or the recent green energy push driving up biodiesel demand.

Early estimates suggest 2021/22 soybean carryout will be a mere 26 million bushels. It would be an historic new low for the stocks-to-use ratio, which would shrink to 0.6% - the tightest level on record. Furthermore, it means there are only 2 days of carryout between the old crop running out and the start of the 2022 harvest season.

Logistically and statistically, it is not likely that 2021/22 soybean stocks to use ratio will drop to less than 2.5%. Usage will inevitably have to drop, which means a couple economic events are much more likely to happen a year from now: first, demand rationing will likely become more commonplace as buyers are outbid for dwindling stocks. Soy consumers, including crush facilities, hog and poultry feeders, and biodiesel producers, are likely to scale back output amid rising input costs.

But it also means that farmers could see another year of record returns after several years of depressed commodity prices, provided demand continues to strengthen. It will certainly make marketing decisions easier in this new era of tightening supplies and higher prices.

Wheat acres surge higher

Wheat prices finally saw downside movement this morning after USDA��’s acreage estimates came in just over 3% higher than the average trade estimates. The wheat complex largely followed corn and soybean prices higher this morning despite the potential for an increase to supplies in 2021.

But it is not yet known how winterkill damage from February cold snaps and lingering drought effects are going to impact 2021 yields. Heavy rains and snowfall in mid-March helped boost crop conditions in the U.S. Plains, where nearly 82% of acreage remains in some form of dry or drought condition.

Crop damage remains possible from a turbulent La Niña winter and the prospect could lead to a smaller crop than the current estimate of nearly 1.9 billion bushels. And –unfortunately for farmers – it means that for wheat prices to continue to support a rally independent of corn and soybeans in an era of increasing global production, taking a hit on growing conditions will be somewhat necessary to compete with corn and soy profits this year.

Uncertainty remains the largest unknown

It is possible that market guesses did not factor in other, more qualitative factors into Wednesday’s report. As mentioned before, moisture stress is a serious and ongoing concern in the Plains and Western states – areas where marginal acres will be the deciding factor in final crop rotations. NOAA’s short-term forecasts suggests the dry weather will continue, which will play a deciding factor in how final acreages shake out.

And just because vaccines are here and being more widely distributed doesn’t mean that the pain of the last year has been erased from the market’s mentality. The pandemic’s onsets exposed many serious shortcomings of the global supply chain and agriculture was anything but exempt from the fallout.

Hog producers have shrunk herds by 2% over the past year amid COVID-19 related slowdowns at meat packing facilities. Calendar year to date egg sets are 1.4% lower than the same time in 2020. February’s cold snap idled ethanol and soy crush output and stalled petrochemical production that is necessary for food packaging. Across the food industry, key market players are continuing to adapt operations to continue safe production in the pandemic era.

So maybe it’s no surprise that USDA’s acreage numbers came in uncharacteristically lower than in previous years. After two years of wildly anomalous growing seasons and an unprecedented economic disruption, maybe the markets are as unsure as I am about how the world is going to look over the next few months.

Quarterly stocks – reading the tea leaves

There was much less chatter surrounding Wednesday’s Quarterly Stocks Report compared to the 2021 acreage estimates. But that didn’t mean there was nothing to see in the updated dataset.

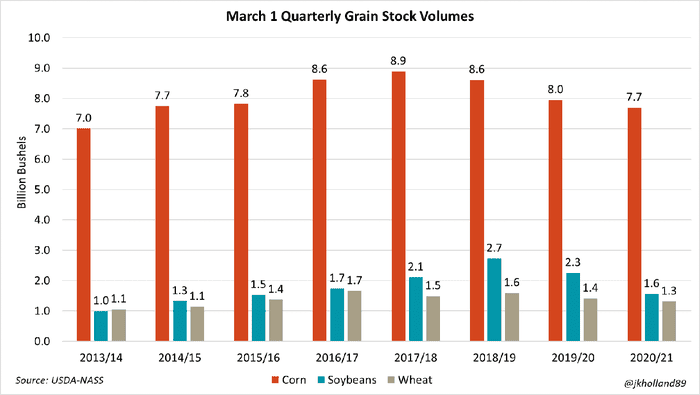

USDA’s December 1, 2020 – March 1, 2021 usage rates largely aligned with market expectations. March 1, 2021 corn, soybean, and wheat inventories fell 3%, 31%, and 7%, respectively, from the year prior on eye-popping export rates and two consecutive years of smaller than expected crops.

At 7.7 billion bushels, this year’s March 1 corn inventory recorded the lowest volume since 2013/14 (7.0 billion bushels). Stocks fell nearly 32% from December 1, 2020, indicating the highest usage rate also since 2013/14 (33%).

Soybean supplies also rapidly vanished during the quarter thanks to heavy export demand from China amid ongoing Brazilian soybean shipping delays. The March 1, 2021 soybean stock reading of 1.56 billion bushels indicated the most rapid second quarter soybean disappearance rates since 2014/15 and the smallest March 1 inventory volume since 2015/16.

USDA also made significant adjustments to December 1, 2020 corn, soybean, and wheat stocks. Lance Honig, the Crops Branch Chief at USDA-NASS, noted in USDA-NASS’s #StatChat on Twitter following the report release that late changes to off-farm and commercial storage facilities were significant enough to warrant a change.

But there could be more at play here. The off-farm adjustments for the previous quarter are becoming a more regular phenomenon in USDA’s quarterly stocks report as evidenced by revisions to previous quarters on the last two quarterly stocks report releases, much to market watchers’ chagrin.

And it begs the question: Are we moving to a supply chain that focuses less on “just-in-time” production methodology in favor of a “just-in-case” approach? If global wheat trade is any indicator, it may be happening quicker than previously thought.

USDA’s World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) for global wheat imports currently sits at just over 7.0 billion bushels for the 2020/21 marketing year. But as of last May, that estimate was only 6.7 billion bushels. That’s nearly a 5% increase in global wheat import volumes in a 10-month span.

Feed consumption is a key driver behind that statistic but consider this – in Wednesday’s report USDA revised December 1, 2020 quarterly wheat and soybean stocks 1.7% and 0.5%, respectively, higher after late reports from off-farm commercial storage facilities were received by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).

Could this be an indicator of commercial buyers stockpiling grain supplies to buffer against future production hiccups, similar to what was experienced at the height of the pandemic? A look a strong basis prices across the Heartland lends credibility to the notion. And the current futures price inversion which favors selling grains sooner rather than later also supports a shift in grain buying behaviors.

Though it may be too early to tell. And of course, Corn stocks for last December fell 0.2% due to updated commercial storage volumes, which does not lend itself to the “just-in-case” philosophy. But it will make future Quarterly Grain Stocks reports increasingly important to market watchers to see if this pattern becomes more than just a trend.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like