September 13, 2018

By Joe Mahon

It wouldn’t be controversial to say that immigration is controversial. But in Worthington, Minn., the residents of the city of about 13,000 speak with a fairly unified voice: Immigration is good for our economy.

That’s the message that Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank President Neel Kashkari heard when he traveled there last summer to learn about how immigration has affected the city in southwestern Minnesota, about 60 miles from the South Dakota border.

While in Worthington, Kashkari and bank staff participated in a community forum about the immigrant experience on the eve of the town’s International Festival. They also held a listening session with immigrant entrepreneurs and toured a large meat packing plant — the city’s biggest employer, whose labor force is largely made up of immigrants — sitting down with a diverse array of workers there to hear about the workers’ experiences.

Previous outreach trips have focused on the broad economies of Ninth Federal Reserve District communities, including meetings with a cross section of businesses and individuals that make those respective places tick. However, this visit centered more narrowly on the subject of immigration and its effect on regional demographics and livelihoods of communities like Worthington: smaller-to-medium-sized population centers in rural areas.

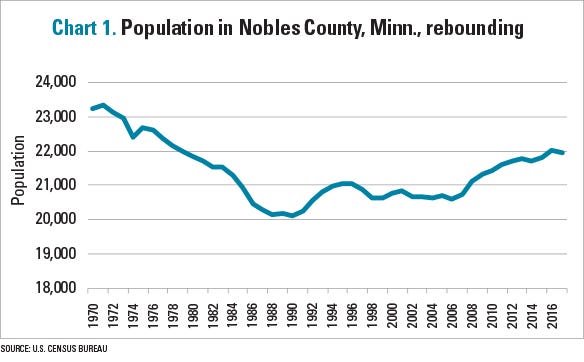

Population in Nobles County rebounding

Like many rural communities in the district and beyond, Worthington saw a long period of population decline, beginning in the mid-20th century. This decline continued until the late 1980s and suddenly rebounded, as illustrated in Chart 1, which shows the annual population estimates for surrounding Nobles County. Worthington is the county seat and accounts for three-fifths of the county population.

The rebound coincided roughly with the beginning of the flow of new immigrants. The word “new” has to be stressed, because the area around Worthington, like much of rural America, was settled by an earlier wave of European immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of the early immigrants in this new period were Hmong and Laotian.

“This really started with the churches 40 years ago; they started to sponsor and invite refugees from Southeast Asia,” said Worthington Mayor Mike Kuhle, reflecting on how the city became more diverse.

Immigrants' growing population in Worthington

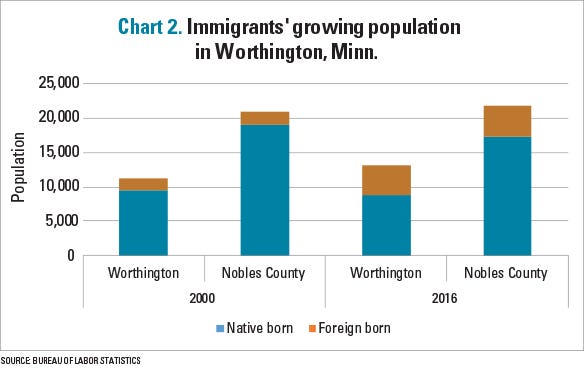

By 2000, nearly 16% of Worthington’s population was foreign-born. But the influx of immigrants has really accelerated since the turn of the millennium. As of 2016, the most recent year for which U.S. Census data are available, nearly one-third of Worthington residents were born overseas. Chart 2 illustrates how crucial immigration has been to the city’s overall growth.

Since 2000, Worthington’s population has grown 17%, and the county population has increased 5%. Numerous immigrant businesses have opened to serve residents. By comparison, population growth for all nonmetro Minnesota counties was less than 2% over the same period, and the native-born population of both Worthington and Nobles County actually fell.

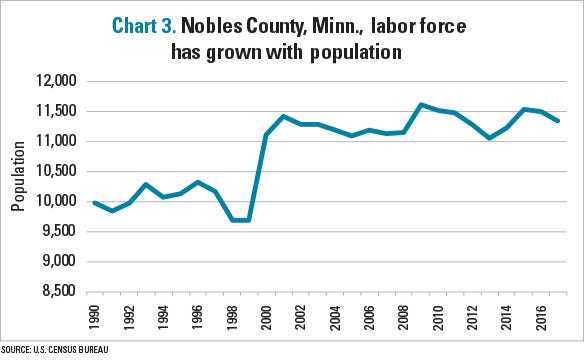

County labor force grows with population

Why are so many immigrants coming to Worthington? One obvious reason is economic opportunity. That is reflected in the growth of the labor force along with the population, as shown in Chart 3. Unemployment in the county averaged 3.2% in 2017, lower than the state rate. This again stands in contrast to many rural counties, which typically have higher unemployment rates than the state.

Many new arrivals start out working at the JBS hog processing plant, where Minneapolis Fed staff took a tour and met with workers. The plant employs more than 2,200 workers, and because the work is hard, the turnover is high and there are frequent openings. Len Bakken, the JBS human resources manager who shared a stage at the community forum with Kashkari, said the plant hires 15 people a week. The current starting wage is about $15 an hour.

Not all new residents end up at the plant, however. Miguel Rivas, who moved to Worthington from El Salvador in 1999, started out milking cows. He then worked a variety of jobs before starting his business selling computers and later, cellphones. Many of Rivas’ customers are Hispanic, a community that now constitutes Worthington’s largest demographic group. Hispanics account for two-fifths of the city population (including both native and foreign-born Hispanics), just barely edging out non-Hispanic whites by a few tenths of a percent.

Rivas, along with other immigrant business owners, discussed his successes and challenges with Kashkari, who observed that many of the hurdles the business owners highlighted — access to credit, navigating regulations, finding good employees — are the same challenges any entrepreneur would face, immigrant or not.

Challenge of diversity

However, the entrepreneurs also pointed to cultural and linguistic barriers in trying to convince lenders that their businesses had a viable market. Greg Raymo, a banker in Worthington, said these challenges have gotten easier with the second-generation children of immigrants able to serve as ambassadors.

“It’s not uncommon for a 12-year-old to come to the bank with her parents to help them apply for a loan,” Raymo said.

Rivas and others also pointed to the growing diversity in Worthington as a challenge in itself.

“It’s good, but it’s hard too,” Rivas said. His employees speak Spanish and/or English, but dozens of languages are now spoken in the city.

Beyond economic opportunity, others described the benefits of small-town life as an attraction, particularly safety. Abebe Abetew, a native of Ethiopia who lived in Washington, D.C., before moving to Worthington to work at JBS, pointed to the low crime rate and low cost of living as amenities, as well as a short commute time.

“When I lived in D.C., I spent three hours a day getting to and from work. Now my commute is five minutes,” he said.

Conversations in Worthington covered more than just the positive aspects of the community for immigrants, however. Some community members criticized a lack of immigrants in city government — particularly on the police force.

Still, most immigrants with whom Kashkari met generally described Worthington as welcoming and said they considered themselves a part of the community. Kuhle attributed this to decades of experience developing a model of inclusiveness, including active faith communities taking the lead to resettle refugees and other immigrants.

“You just don’t turn the lightbulb on, and you’ve got people here. There’s a lot of hard work,” Kuhle said.

When Natalie Nkashama, a Congolese social worker and market owner who previously lived in Minneapolis, told her friends about her plans to relocate to Worthington, they warned her about moving to a small town where they said the residents would be overwhelmingly racist. But that hasn’t been her experience, she said.

“I’m glad I didn’t listen to them,” Nkashama said,

Rivas also said he was glad he made the decision to move to a small town in southwestern Minnesota. “I feel like Worthington is home,” he added.

This article originally appeared online July 18 in the fedgazette, a publication of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Mahon is a regional outreach director for the Federal Reserve.

You May Also Like