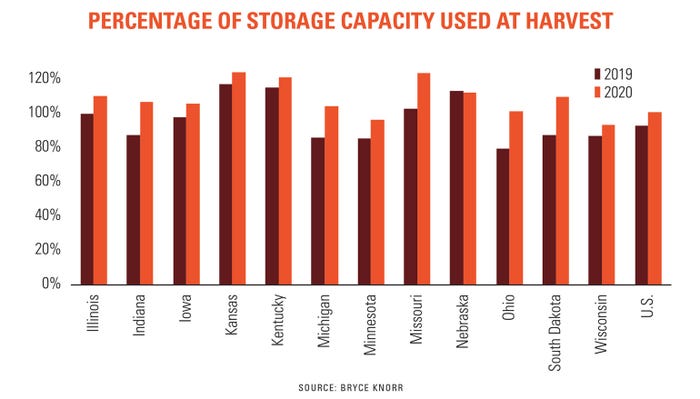

Storage is a cornerstone of most farmers’ marketing plans. The need to avoid pricing grain at harvest, often when markets are weak, helped create the futures industry in the 19th century. And it’s why farmers and merchandisers built enough bins and bunkers across the U.S. to hold more than 25 billion bushels of crops.

But effective marketing doesn’t mean just filling up your on-farm facilities, if any, or sending the rest to town for a warehouse receipt. Tailoring storage decisions to suit both your market and farm’s individual characteristics can help avoid turning a bin from a profit center to a money pit.

Instead, consider creating a decision tree specific to your situation. Here are some keys to consider when crafting that plan.

Storage facilities

On-farm bins account for some 53% of the nation’s storage capacity. Having made the investment the natural inclination is to use it. But using that storage, other than as a holding place while bushels are dried, shouldn’t be an automatic default. Always treating bins as a separate profit center is one way to track their ability to perform for your own operation.

To be sure, there are advantages to owning grain after harvest. Having title to your harvest lets you pledge grain as collateral for CCC or other loans. Interest rates are at record lows, and likely to stay that way into 2022 as the Federal Reserve fights to pump up the money supply to aid economic recovery. Cheap money reduces the cost of holding grain, providing cash to pay bills.

But just because you own or have access to storage doesn’t mean it must be used. Depending on insurance and regulatory restrictions, you may be able to lease out facilities to neighbors needing storage and willing to take the risk it involves.

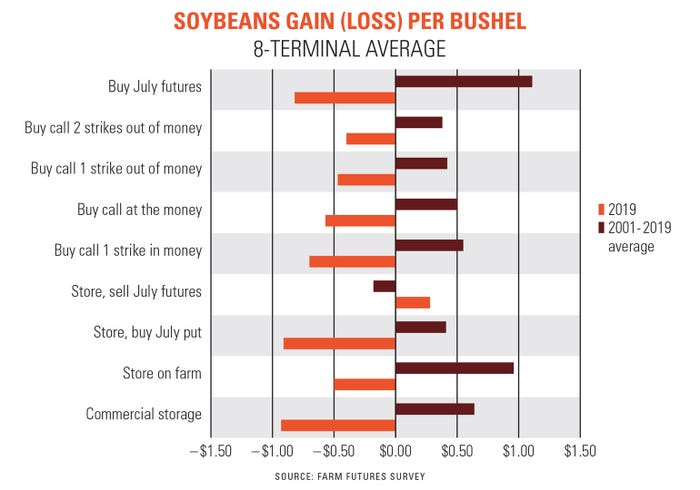

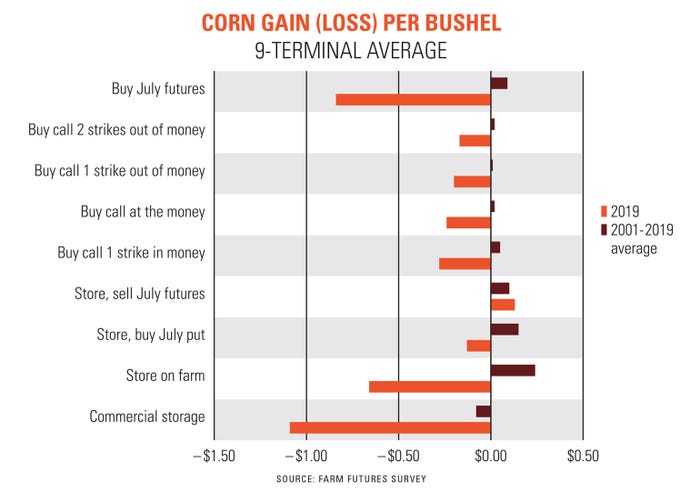

The cost of commercial storage should always be a red flag, or at least a yellow one, especially for corn. It lost an average of six cents a bushel according to our long-term study of storage strategies during the 1985 to 2019 marketing years, beating the harvest price only 34% of the time.

Storing soybeans in town was a better bet in our study, netting 37 cents a bushel and beating the harvest price 51% of the time. But even with beans, there may be better alternatives, at least year in and year out.

The market

Real estate agents have a mantra: Location, location, location. It’s true for the grain market, too. Where your farms are positioned and where you can sell production matters. An operation in the upper Midwest with access to the Mississippi River may need to wait until traffic starts moving again in the spring to make sales. Growers with access to ethanol plants or livestock feeders may have more choices; those end users need grain day in and day out and often can’t store what they need on site.

Still, as 2019 and 2020 demonstrated, even those buyers aren’t infallible sources of demand. And even in a normal environment free of trade wars, floods and pandemics, markets are constantly in flux. One measure of this is basis, the difference between cash and futures.

Weak harvest basis, especially when measured against deferred futures for delivery in spring or summer, increases odds for physical storage of corn to pay off, even if that means paying an elevator. It also makes storage hedges for soybeans look more attractive.

But on average, basis gains in soybeans don’t last. As a result, selling cash at harvest and buying futures, or using a basis contract, beat on-farm storage in our study, though it entailed similar risk overall.

Tolerance for risk

Potential for gain is one way to make a storage decisions. But downside risk is another important yardstick, especially for operations that can’t or don’t want to suffer significant losses that could derail growth or even put the farm out of business entirely.

And, make no mistake, any storage strategy entails risk. Storing 2007 crop corn netted an astounding $3.10 a bushel more than the harvest price at the locations we studied after prices nearly doubled during the big 2008 bull market. But waiting too long to sell the 2019 crop meant losing 66 cents a bushel.

Risk tolerance involves more than money. Fear of losses can lead to panicked decisions that only compound the trouble. Those who know they can’t control these emotions may be better off taking less risk, even if their balance sheet can afford it.

Cash flow needs

Basis on old crop grain in storage tends to be weak in February for a couple of reason. Northern stretches of the Mississippi are closed and the advancing South American harvest weakens export movement. But cash also trends softer because farmers are forced to make sales as loans come due March 1. Too much supply overwhelms limited demand, and the cash market suffers.

Planning the need for cash can avoid selling into seasonal weakness. Using forward contracts that lock in basis and futures, for example, are one tool to boost storage returns. Knowing when you’ll need funds can help you prepare a realistic storage marketing plan that minimizes risk of dumping grain into a weak market.

Selling in regular increments is another way to make sure you have adequate cash and also has another advantage: It increases potential to receive at least the average price for the crop. Sometimes average is okay, especially for those with limited tolerance for risk.

Ability to use marketing tools

It’s one thing to talk about strategies like the storage hedge. But if you’re not comfortable selling futures contracts, hedging for basis appreciation my just be a theory. Commissions and fees on futures trades at some brokers are a dollar or less per truckload. But some elevators charge much more to use or roll hedge-to-arrive contracts, another way to put on a storage hedge.

Knowing the limitations of your skill-set – or taking steps to learn more – should also factor into your storage decision. If you’re strictly a sell-out-of-the-bin marketer your alternatives will be limited.

All tools are not created equal, of course, in their potential for risk and reward. Options cost money and these premiums must be paid in advance, but the insurance many times pays off only if markets make a significant move. Average returns in our study for corn calls were just a couple cents a bushel for corn. Soybean calls fared better but under-performed the harvest price five out of the last six years.

Still, using a variety of tools could be one way to control risk. Corn calls on their own may be lottery tickets. But when combined with storage hedges they could be useful, creating a “synthetic” put option on inventory. If the market explodes, say on drought concerns in early June, the calls could add to profits from strengthening basis.

Outlook

It’s natural to be bullish after investing time and money – a lot of both – into raising a crop. But even a well-informed forecast on any market can be wrong much of the time.

Historically, the ratio of marketing year ending stocks to usage correlates with the average cash price received by farmers. The smaller this ratio, also expressed as they number of days’ supply, the higher the price.

But tighter supplies don’t ensure bins make money in corn, where this measure does not correlate to storage returns. This year, for example, 2020 corn supplies are likely to be burdensome. The market could still rally in the spring and early summer of 2021 if drought returns to the Midwest.

Soybean storage profits show a much stronger connection to the stocks-to-use ratio. Soybean prices appear more variable after harvest depending on South American weather and international demand. China’s appetite for soybeans for many years turned out better than forecast – until it didn’t – and both factors could be in play for 2020 inventory.

La Nina forecast to develop this fall is associated with lower yields in Argentina, for one. And the crucial U.S.-China relationship has many potential flashpoints that could affect sales. As the last few years provided, nothing is certain. So make sure storage plans can react to events if needed.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like