China is not always well-liked, but it has given the U.S. farmer insatiable demand that has lifted prices — and could continue to do so through the fall of 2022.

In the last nine months, the United States set a record for U.S. agricultural exports to China. The two-year Phase 1 trade deal negotiated under the Trump administration will expire by year-end. It includes a lofty goal: $40 billion in ag purchases per year. China’s ag imports are roughly $150 billion per year from all over the world.

Through June, China’s purchases of U.S. ag products were on pace to hit $33.7 billion for this year. Seasonal soybean purchases, usually happening October through December, historically account for over half of annual soybean purchases.

“The fact we can [possibly reach] $40 billion is not a pipe dream at all,” say Gregg Doud, former U.S. agricultural trade negotiator in the Trump White House.

But what could happen to trade on Jan. 1? The U.S. will still have $360 billion worth of tariffs on imports from China, but all the structural changes negotiated in the Phase 1 agreement will stand. Even so, it’s likely China will try to create leverage in an attempt to eliminate those $360 billion in tariffs.

“Things are good now, and they can continue to be good, but there will be uncertainty and friction with all of this,” says Doud, who now serves as the chief economist at Aimpoint Research.

A little history

Dhamu Thamodaran, a retired chief commodity hedging officer for Smithfield Foods, says when the trade war started in 2018, China retaliated with a 50% tariff on pork. The Phase 1 deal lowered the tariff on pork from 50% to 25%.

China produces half of the world’s pork and consumes more than half of the world’s pork, too. But after being faced with the decimation of its domestic herd due to African swine fever, the country had to purchase record amounts of pork to meet domestic demand. This led to record pork purchases from the U.S., despite tariffs.

China not only bought U.S. pork, but also the feed that goes into its herd as it rebuilt after ASF. No one knows for sure where this “rebuild” is at, but some estimates put the hog population at 90% of previous levels.

The herd rebuild includes investment in modern production methods and facilities. Some of China’s pigs live in high-rise hotels with 1,000 hogs per floor. In a post-ASF world, fewer animals are raised in less-hygienic, 1-acre peasant farms.

Part of this new approach includes a ban on feeding swill, or food waste, to herds. This has boosted demand for feed grains, including soybeans for crushing and corn.

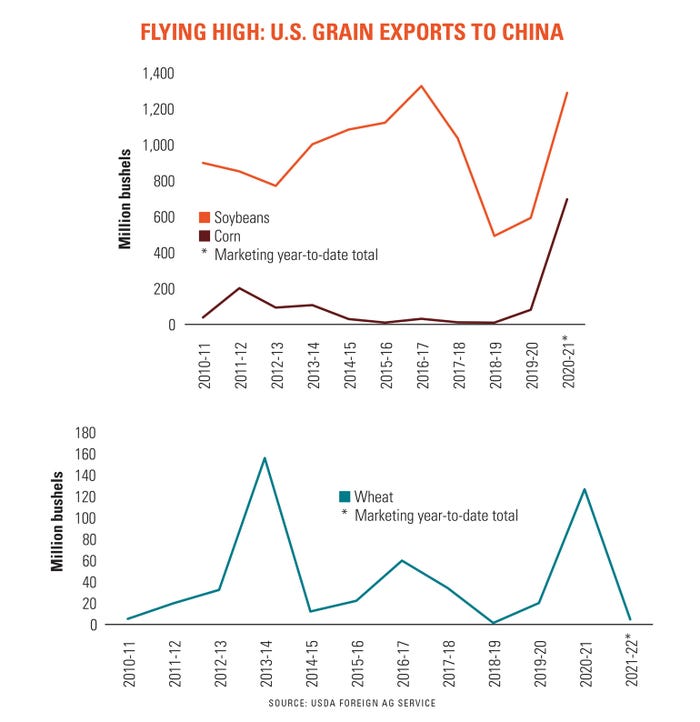

To secure feed, China has bought massive amounts of U.S. corn in recent years, a far cry from pre-2015 years when the country was building stocks with its costly price support policy — leading to the U.S. filing a complaint to the World Trade Organization for excessive corn subsidies. (China adopted a direct payment corn subsidy policy tied to planting acres in spring 2016.)

Chinese corn demand is hard to pin down because transparency has dropped considerably in recent months, with rumors that ASF still rages across China’s hog herd. Doud says the lack of transparency is because “they don’t want to be in a situation where they feel trapped in the marketplace.”

Even so, the U.S. is likely China’s only supplier for corn until March. Seasonally, imports of soybeans tilt to the United States’ favor from September until February before Brazil takes over. Doud says last year during that time frame, shipments were maxed out, and that was with a 500 million-bushel soybean carryout, which isn’t there this year.

The global supply-and-demand for corn and soybeans remains tight. With the price of corn in Brazil at over $8 per bushel, and China priced at $10 to $11 per bushel, Doud doesn’t see much downside potential of lower commodity prices in the near term.

U.S. beef to China surged thirteenfold in both exports and sales from January to May compared to the same period last year, reports USDA’s Foreign Agriculture Service. That expanded market access came after eliminating several long-standing non-tariff barriers in the Phase 1 agreement.

Through May, China ranked as the largest U.S. market by both volume and value, surpassing both Mexico and Canada, which have historically been ranked as top U.S. markets.

Freight headwinds

So now you’re thinking: What could screw this up? Look to the seas for answers. Ocean freight costs are double what they were a year ago, and boat freight may not expand for two to three years as supply chain pandemic pressures continue.

This is in addition to an already dramatic shortage of shipping containers. Imports have affected vessel operations and container availability, diminishing export options for U.S. products, including produce, wine, dairy and fresh pork. The largest 10 shipping companies control more than 80% of shipping, leaving domestic manufacturers that need to export goods at the mercy of these large foreign companies.

Limited container access hits some ag sectors more than others. The pork industry, for example, gets a premium for exporting fresh vs. frozen cuts.

Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., says on the West Coast, containers come to America, are emptied, and then returned to China empty instead of waiting for U.S. goods to be loaded.

“They just simply sent them back to China empty, leaving no ability for American agricultural exporters to get a container, let alone get them on a ship,” he says.

According to the Agriculture Transportation Coalition, “… on average 22% of U.S. agriculture foreign sales cannot be completed due to ocean carrier rates, declining to carry export cargo, unreasonable demurrage and detention charges, and other practices.”

The cost to move a container from China to the U.S. West Coast has a spot rate of $6,288, while the cost to move containers full of goods from the West Coast back to China is $986, says Mike Steenhoek, executive director of the Soybean Transportation Coalition.

With those rates at six times the value of bringing in the product from China to the U.S. versus taking from the West Coast to China, it’s no wonder those Chinese shippers are trying to turn those boats back around as quick as they can.

New legislation, the Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2021, looks to support U.S. exports by establishing reciprocal trade opportunities to help reduce the United States’ long-standing trade imbalance with China and other countries, and establish rules of the road for fair trading.

Limited options

With a limited land base and 1.4 billion people to feed, China has made greater self-sufficiency a priority to reduce reliance on imports. And it especially does not want to rely on the U.S., considering fresh memories of the recent trade war.

Even so, China has few short-term options for sourcing certain ag goods — until at least next fall.

“I don’t think there’s potential for commodity prices to come down,” Doud says. “When it comes to the global supply-and-demand of protein, corn and soybeans, I don’t think there’s any way to bring prices down until after next year’s U.S. harvest at the earliest.”

The added good news is U.S. ag exports to other markets, in addition to China, are strong.

The question going forward is whether brisk sales of meat and feed grains to the Philippines and Indonesia can keep chugging along at current volumes. The telltale sign will be whether trade starts to fall off at the current higher prices.

“If they can afford it, we’re in good shape for a long time,” Doud concludes.

Read more about:

ChinaAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like