You know one thing for sure: Corn yields are increasing — to the tune of 2 bushels per year, on average; even faster on highly productive soils. Okay, maybe not this year on your farm. But it's a clear, strong, long-term trend.

Yield plot gains appear even bigger, asserts Joel Wipperfurth, director of ag technology for Winfield United. Eight years ago, Winfield's Answer Plots showed that only three replicated corn yields from five different seed companies hit 300 bushels in their Illinois plots. Last year, nearly 147 replications hit 300 bushels.

Bigger yield means bigger risk, begging a bigger question: How do you manage 300 bushels' worth of inputs, when the weather is, at best, volatile? And how can knowing more about weather trends help you manage those inputs — and help your soil adapt?

"You can't put 300 bushels' worth of inputs down in the fall and expect them to be taken up in the spring and be there," Wipperfurth says. "When you get a quarter inch of rain, soil can handle it. When you get 5 inches of rain, soil can't handle it and it runs off."

Wipperfurth, like many of his colleagues in the nutrient and weather businesses, says changing weather patterns in Illinois and beyond mean farmers need to prepare their soils to take up more water — and retain it during droughts.

"What if you knew that the next 10 years would be about preparing your soil structure to receive 6-inch rainfalls, and that to capture yield it would be about retaining that 6-inch rainfall — without leaching nutrients away?" Wipperfurth asks.

Identifying big trends

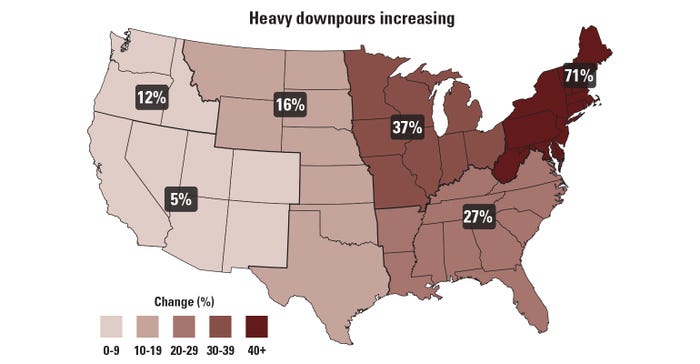

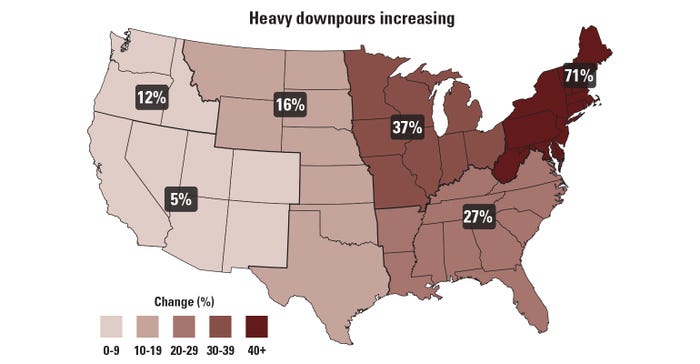

Eric Snodgrass, Agrible co-founder and atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois, agrees, and he says there are big underlying trends in weather. Knowing about them could help you mitigate risk. While the National Climate Assessment is already four years old, its trend lines are holding for the northern Corn Belt and the Northeast.

"Year-to-year variability is always high," he says. "But big trends shift you incrementally throughout the years you farm."

The percent of rainfall occurring in very heavy events has dramatically increased in the Northeast from 1958-2012. "This shows how much of our annual rainfall is coming from larger rainfall events, of over 2 inches in 24 hours," explains Eric Snodgrass, Agrible co-founder and atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois.

The percent of rainfall occurring in very heavy events has dramatically increased in the Northeast from 1958-2012. "This shows how much of our annual rainfall is coming from larger rainfall events, of over 2 inches in 24 hours," explains Eric Snodgrass, Agrible co-founder and atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois.

Snodgrass sees three big trends for the upper Midwest and Northeast:

• More downpours. Rainfall patterns have made statistically significant changes over the past 70 years. Illinois, for instance, still gets 40 inches a year, but in big events. That makes tile more important, Snodgrass says. It also makes nutrient application and retention even more important — along with soil health, so soils can absorb and retain moisture when needed.

"There's a high probability that we'll get our 40 inches from four big events," Snodgrass says. That doesn't mean it'll happen every year. But the underlying trend is still there.

Watch for setups in the upper atmosphere that result in strong flow out of the Gulf of Mexico, Snodgrass warns. That can pump enormous amounts of moisture north and eastward. Not all of it will be hurricane-force.

The Northeast has perhaps the most diverse climate, according to the National Climate Assessment report. Average annual precipitation varies by about 20 inches, with the highest amounts in coastal and select mountainous regions.

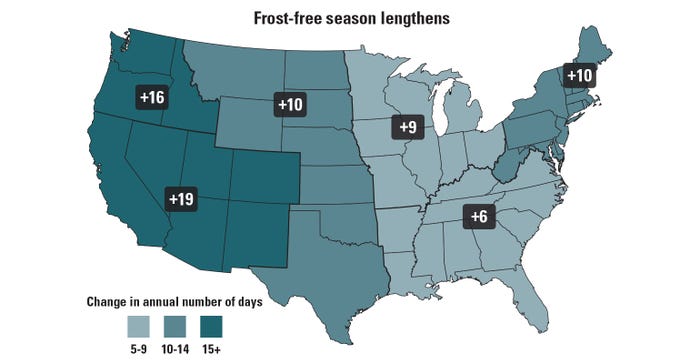

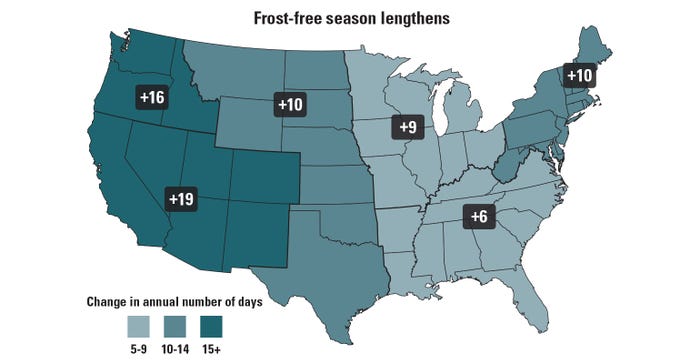

Frost-free days are on the rise, as defined as the period between the last occurrence of 32 degrees F in the spring and the first occurrence of 32 degrees F in the fall. This map, based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data, shows the increase in frost-free season length from 1991-2012, relative to 1901-1960.

• Longer growing seasons. Specific to the lengthening frost-free seasons, Snodgrass says the effect is greatest in the northern states where the growing season has increased by nearly a month. That's one reason why more New York farmers now grow soybeans, and why Pennsylvania's 2018 soybean acreage may hit a second-consecutive record.

• More heat waves. Frequency, intensity and duration of heat waves is expected to increase, according to the NCA report. Much of the southern portion of the region, including most of Maryland and Delaware and southwestern West Virginia and New Jersey, are projected by mid-century to experience 15-30 days per year above 90 degrees F. Increased frequency of summer heat stress is also projected, which can negatively affect crop yields and milk production.

Offset your weather risks

What can you do? First, analyze the trend implications for your farm and soils. Build soil structure through cover crops and reducing tillage and compaction. Wipperfurth says improving soil structure keeps rain from carrying off topsoil. Increasing water-holding capacity is important when there are greater distances between rainfalls.

More weather variability also means fewer operating days, putting pressure on equipment to be right-sized. He suggests current weather patterns may require you to run two planters. Or maybe you'd be ahead to have multiple autonomous 20-hp tractors running when conditions are moderate, instead of one big four-wheel-drive tractor running when it's a little too wet.

"When labor is no longer the limiting factor, farmers will make in-season input applications multiple times in a season," he predicts. "When you know the weather trend is for higher amounts of rainfall, hold off on inputs until the plant needs it. Put just enough nitrogen out there until you get to the next point where you need to make the next decision."

Wipperfurth's rallying cry is that farmers need to measure what they're trying to manage, through tissue sampling, nitrate sampling and crop modeling. Agronomic companies are increasingly offering mapping and application programs to help offset soil loss and increase soil health.

Winfield/Land O'Lakes Sustain program, for instance, maps elevation and lets you analyze the tons of soil you can lose at different combinations of management. "If you know you lose a ton of soil that's valued at $100 per acre," he adds, "then $30 an acre for a cover crop doesn't look so bad."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like