Big speculators turned massive sellers in corn and soybeans into mid-March, dumping bullish bets that prices would rise. But while the herd of professional traders stampeded to the exits, some also placed long-shot wagers that would pay off on volatile markets this summer.

Buying commodity lottery tickets was nothing new for these money managers. Unusually large trades in out-of-the-money November 2017 soybean calls began showing up in December. But the activity ramped up as the market sold off, making the positions cheaper to establish.

These out-of-the-money calls give buyers the right to buy futures at a price that’s above the market by $1, $2 or even $3.The odds futures will rally to those levels is low, but these long-shot bets don’t cost much either.

Not all the positions were bullish. Some were cheap ways to profit from a selloff in soybeans even deeper than the one that hit the market last fall. And in the corn market, wagers on drought were joined by bets prices would move big in either direction.

Here’s a look at some of these trades, and their prospects for a payoff.

Options terminology

Call options convey the right but not the obligation to buy futures at a predetermined strike price.

Put options convey the right but not the obligation to sell futures at a predetermined strike price.

Delta measures the amount an options position reflects changes in movements of its underlying futures contract.

Implied volatility measures the relative risk the market sees in prices of a futures contract changing. The higher the volatility, the more costly an option may be because buyers and sellers believe the risk of futures prices movement is greater.

Intrinsic value is how much of an option’s premium is could be captured if the put or call were exercised immediately.

Time value is how much of an options premium is not due to intrinsic value. The longer an option has until expiration, the greater its time value will be if implied volatility does not change.

Premium is the cost buyers pay for an option, up front, to sellers.

1. Buy November $11 call, sell November $12 call

This trade, known as a bull call spread, helps lower the cost of a long call by selling another at a higher strike price. The call that is sold caps the maximum gain from the position to $1, less the net cost of the premiums paid and received, as well as fees and commissions.

This spread started buzzing back on Dec. 7, when more than 14,000 were opened, more than half the total of all soybean options changing hands that day. By mid-March open interest in these calls was each running around 30,000 contracts, 50% of the entire open interest in all November options. In addition to the $11 and $12 calls the $13 strike was also active; the three had more open interest than any other soybean options, puts or calls, of any month.

Traders putting on the spread in mid-March could have bought an $11 call for 31.375 cents and sold a $12 call for 16.75 cents. The net cost of the spread was 14.625 cents, plus commissions, with a maximum payout at expiration Oct. 27 of 85.375 cents – the $1 difference between the strike prices of the two options and the net premium, less commissions.

Traders figure their odds from a strategy based on volatilities in the options market. These implied around a 15% chance of November futures hitting $12 before expiration, with a better than 50% chance of reaching $11. Traders, unlike farmers, don’t tend to hold options until they expire. The strategy has an initial delta of 12.65% -- that’s how much of a change in the underlying November futures it will reflect. So, even a modest move would return something. A mid-July rally to $10.75 would gain almost 10 cents a bushel, assuming no change in the options’ volatilities.

2. Buy $8.20 November put, sell $7.20 November put

While farmers and bullish traders were hoping for rallies, others were quietly amassing positions betting prices would fall – a lot. Odds of a huge break in prices aren’t great. But if U.S. growers harvest another record crop, demand sputters and a cool-down in the global economy sends other markets lower, last year’s lows might not hold.

This strategy is the flip side of the bull call spread. A bear put spread combines the purchase of a put option conveying the right to sell futures with the sale of another put with a lower strike price. Traders were buying November $8.20 puts and selling November $7.20 puts. Both legs are deep-out-of-the-money, suggesting they have little chance of paying off. But that’s the point with lottery tickets isn’t it? You pay a little for a very long shot at making the big bucks.

A least one fund was buying into that strategy March 8, putting on around 3,000 of these spreads. The $8.20 puts were bought for 6.25 cents, and the $7.20 puts sold for 1.625 cents, for a net cost of 4.625 cents. If prices collapsed, the position had a maximum gain at expiration Oct. 27 of 95.375 cents, less commissions.

Odds of a payoff were small: only a 10% chance of closing below $8.20, and less than a 2% chance of finishing at $7.20 or less for the maximum payout. The delta on the position was only 6.5% to start with. But the percent of change in futures prices captured by the position would increase as prices fell. If the market tumbles to $8.50 Sept. 1, the spread’s delta would rise to 28%, netting a profit of 7.1 cents before commissions.

3. Buy $5 December call, sell $6 call

Funds started actively buying December 2017 $5 calls back in December 2016, with almost 4,000 new positions opened on one day alone. More recently, they started selling $6 calls to pay for part of the premium. On several days in mid-May funds put on 4,000 of these bull call spreads. On March 17 the $5 calls closed at 8.25 cents, with the $6 call at 2.875, for a net cost of 5.375 cents. That yielded 94.625 cents maximum upside at expiration Nov. 24, less commissions.

Out-of-the-money calls are low probability wagers. The position has almost a 90% chance of expiring worthless. Its starting delta shows it would capture just 11% of a rally initially. But there are 25% odds of a rally to $5 at some point before expiration Nov. 24.

The most obvious time for a move historically would be during pollination in the first two weeks of July. Even a modest mid-July rally to $4.50 would generate a profit of 5.5 cents, with an increase to $5 gaining more than 19 cents thanks to a delta rising to 39%.

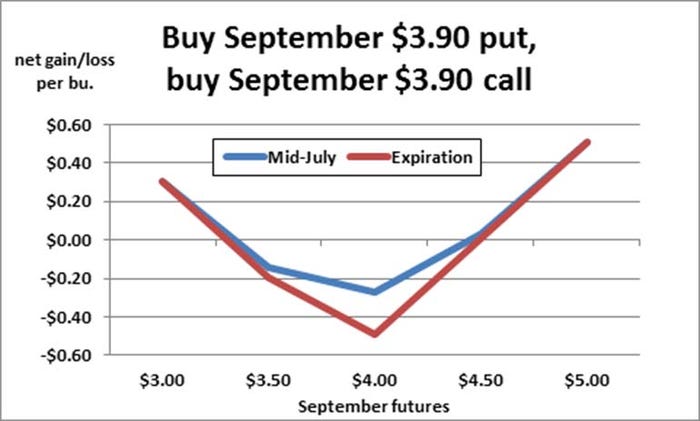

4. Buy September $3.90 call, buy September $3.90 put

Don’t know which way prices are headed? Some money managers address this marketing riddle by buying both a call and put. When these options are at the same strike price and expiration date, the position is known as a long straddle.

This trade was popular in late February, when September futures traded around $3.90. On Feb. 22 around 3,500 of the spreads were put on. The long $3.90 calls were bought for 30.25 cents, the puts sold for 29 cents. The position would turn a profit on expiration Aug. 25 if September was below $3.3075 or above $4.4925 – the $3.90 strike price plus the premiums paid. A move to $5 futures by July 15 would mean a profit of almost 60 cents a bushel before costs; a move to $3 a profit of 30.75 cents if volatilities were unchanged.

Options volatilities implied a 40% chance that would happen. Odds are higher than the other strategies because costs are too – there’s a 60% chance all the premiums would be lost.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like