Soybeans bore the brunt of the impact from the trade war with China. And in the aftermath of the truce in the dispute, soybeans are still in the crosshairs of traders for a simple reason: Beans must do some heavy lifting if the deal has any hope of succeeding.

Indeed, soybean futures broke more than 20 cents in the wake of the agreement because it doesn’t guarantee anything about China’s commitment to any specific agricultural commodity. And with two years to play out, the market will need to see hard evidence of demand before buying in to boost prices.

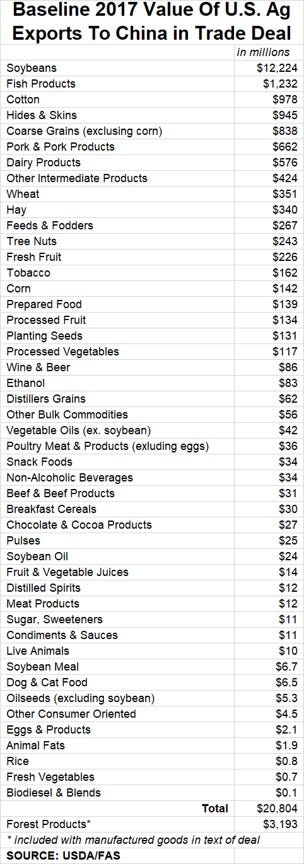

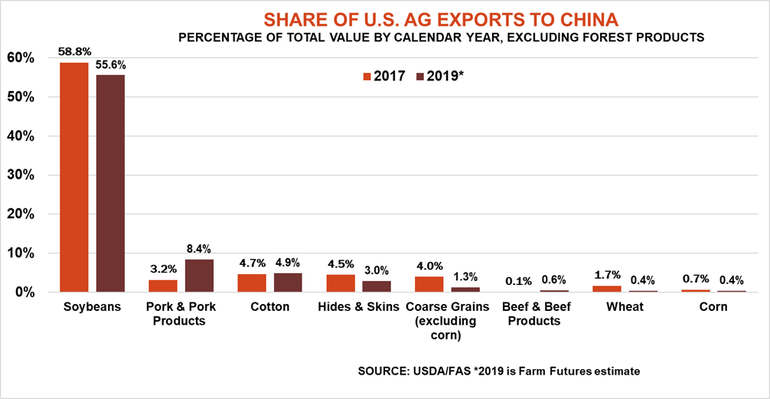

Soybeans accounted for 59% of China’s total ag imports from the U.S. in 2017, the base year used to measure the deal’s progress. No other farm product had more than a 6% share. During the height of the trade war in 2018 China’s soybean purchases from the U.S. dropped by almost 75%. The business started to recover in 2019 as the two sides began finally to hammer out the pact but appears to have totaled less than two-thirds of what it was two years ago.

Daily and weekly news about China’s purchases will be tracked like those big thermometers used in community fund drives. Trouble is, unlike the amount needed for a new fire engine or library addition, the deal doesn’t have a specific goal for soybeans or anything else. Only the total matters: $12.5 billion above the 2017 baseline in 2020 and $19.5 billion more in 2021.

In all, the deal is supposed to bring Chinese purchases of agricultural goods to $80 billion. That total appears to include forest products in the total for ag, even though those are categorized as “other manufactured goods” according to the text of the deal released to the public. “China will also strive to purchase an additional $5 billion of agricultural products annually,” the summary of the pact says.

Another sentence caught they eye of traders and contributed to beans’ selloff:

“The Parties acknowledge that purchases will be made at market prices based on

commercial considerations and that market conditions, particularly in the case of agricultural

goods, may dictate the timing of purchases within any given year.”

Two other factors make evaluating the deal’s impact difficult. First, both governments use calendar-year statistics, not the marketing-year totals favored by the commodity market. The $12.5 billion for 2020 could be backloaded to the 2020 marketing year, not boosting 2019 crop sales as much as needed to generate rallies. Marketing-year totals generally track calendar-year totals, but not always. In years of market disruptions – droughts or trade wars – the totals can vary widely.

Second, the deal is based on total dollars, not quantities. Chinese soybean imports from the U.S. peaked in the 2016 calendar year at 1.325 billion bushels. On a value basis, the best year was 2012. The quantity of sales was only 963 million bushels. But prices were much higher due in part to supplies squeezed by the 2012 drought.

Could soybeans be the key to making the deal work? China’s total imports of the crucial feed ingredient plunged over the past two years in the wake of the trade war and the devastating effects of African Swine Fever on the nation’s hog industry. It could take that long or more for purchases to get pack to the 3.5 billion bushels imported in 2017 from all originations. If China’s total purchases – and prices -- don’t rise more sharply, U.S. ag sales could still increase if the U.S. grabs a greater share of the pie.

A decade ago before the explosion in South American production, the U.S. controlled around 45% of the Chinese market for soybeans. At projected totals for 2020, that could lift U.S. sales to 1.4 billion, adding $3.25 billion above the total reached in the benchmark year of 2017 at current values.

That’s only a quarter of the $12.5 billion outlined in the phase one year. And the total would need to grow in 2021.

Other crops could play a role, but it won’t be easy. First, China must grant waivers or lift retaliatory tariffs on U.S. imports or compensate buyers for the penalties. The text released of the deal is silent on this point.

Then China must begin living up to existing commitments to the World Trade Organization to import some goods under low Tariff Rate Quotas.

Cotton was the number two crop China imported from the U.S. in 2017. But the 533,038 metric tons done that year fell short of the existing TRQ, which will be 894,000 for 2020, and the growth in China’s appetite for cotton appears to be waning due to uncertain global demand for textiles.

Corn and wheat could see incremental gains. China doesn’t import much of either crop, and the U.S. accounts for only 1% or 2% of China’s purchases. As with cotton, the first challenge is getting China to meet its TRQ minimums. But after that the tariff rises to 65% under Most Favored Nation status for the WTO. That penalty is enough to price most U.S. exports out of the market. Around $1.5 billion could be added to the baseline if China matched record corn and wheat purchases from the past.

Coarse grains could have the best short-term chances for a pick-up in business, especially sorghum. It’s used to make a popular liquor. U.S. sorghum sales to China exploded during the 2013-2014 marketing year, then cooled as China applied regulatory restrictions. A return to the boom times could add $800 million to the 2017 baseline.

The livestock sector likely is the bet place to look for gains thanks to ASF. Sales of pork and pork products hit a record in 2019, likely topping $1.2 billion, but accounted for only 15% of China’s total purchases due to the trade war. DDGSs could also see a boost but hopes for ethanol took a hit after the government apparently stepped back from its goal for using E10 nationwide wide by the end of the year.

A billion here, a billion there – it could add up. But time is not on the grain market’s side in the here and now, unless China opens its wallet with both barrels blazing when traders return after next week’s Lunar New Year holidays. And even if China buys more from the U.S., our other customers may turn to the competition if their prices are cheaper.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like