Last year, I argued that commodity markets needed a leader to pull itself out of a bear market (Grains Find a Leader, CSD August 2017). That leader, I hoped, was the spring wheat market at the Minneapolis Grain Exchange. A severe summer drought in the Northern Plains and Canadian Prairies ignited wheat prices, which in turn put a spark into corn and soybeans.

I was a year too early.

The wheat price rally of 2017 was short-lived. Why? The 2017 drought hit parts of the Northern Plains hard, costing the U.S. and Canada about 150 million bushels (4 mmt) in lost wheat production. That sounds like a big number. However, on the other side of the globe, Russia was producing another record wheat crop – 450 million bushels (12.5 mmt) better than the 2016 crop, and three times larger than the North American loss. World wheat stocks increased again, and the bear market continued.

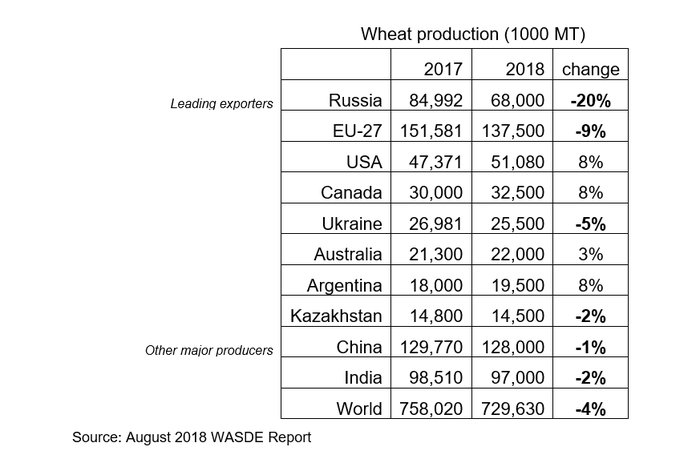

One year later and wheat has once again taken the leadership position in grains. This time, however, it will endure through the crop year because world production problems are much broader. Russia in particular, and the Black Sea region in general, has come back to earth after two great wheat crops. Russia has been the leading the world in wheat exports over the past two years, but their crop will be nearly 17 mmt smaller than a year ago. Europe is a close second in exports, but their crop will be down more than 14 mmt (MATIF milling wheat prices increased $30 per ton in July, to their highest levels in over 4 years). Ukraine and Australia are two more exporters with wheat production problems. All estimates come from the August WASDE report, but news reports from around the world make these numbers sound optimistic. Don’t be surprised if the final production numbers are smaller.

The U.S. and Canada are also major wheat exporters, and crops are on the rebound. However, a little perspective is needed. Despite increased wheat production this year, the U.S. crop is still the second smallest since 2006. A 6 mmt increase in North American wheat production is small compared to the decreases in Russia, Europe and Ukraine. China and India are major wheat producers and, at times, wheat importers. Both countries are facing smaller crops in 2018.

Add it all up and the current year will be the first decrease in world wheat production and ending stocks in five years, and the changes are significant.

Talking about the wheat market in the pages of Corn & Soybean Digest may seem odd, but wheat has the horsepower to lead world grain markets. Wheat prices are more sensitive to changes in supply and demand than corn or soybeans. Why? Because wheat, as a food grain, has few substitutes. If you don’t believe me, try making a loaf of bread, cake or pizza dough from corn or soy flour. Corn, on the other hand, has many substitutes as a feed grain, including wheat. Soybeans also have more substitutes among oilseeds.

Wheat can lead and, in the midst of a trade war, we need a strong leader.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like